If you're confused about the sun's impending magnetic field flip, don't feel bad — scientists don't fully understand it, either.

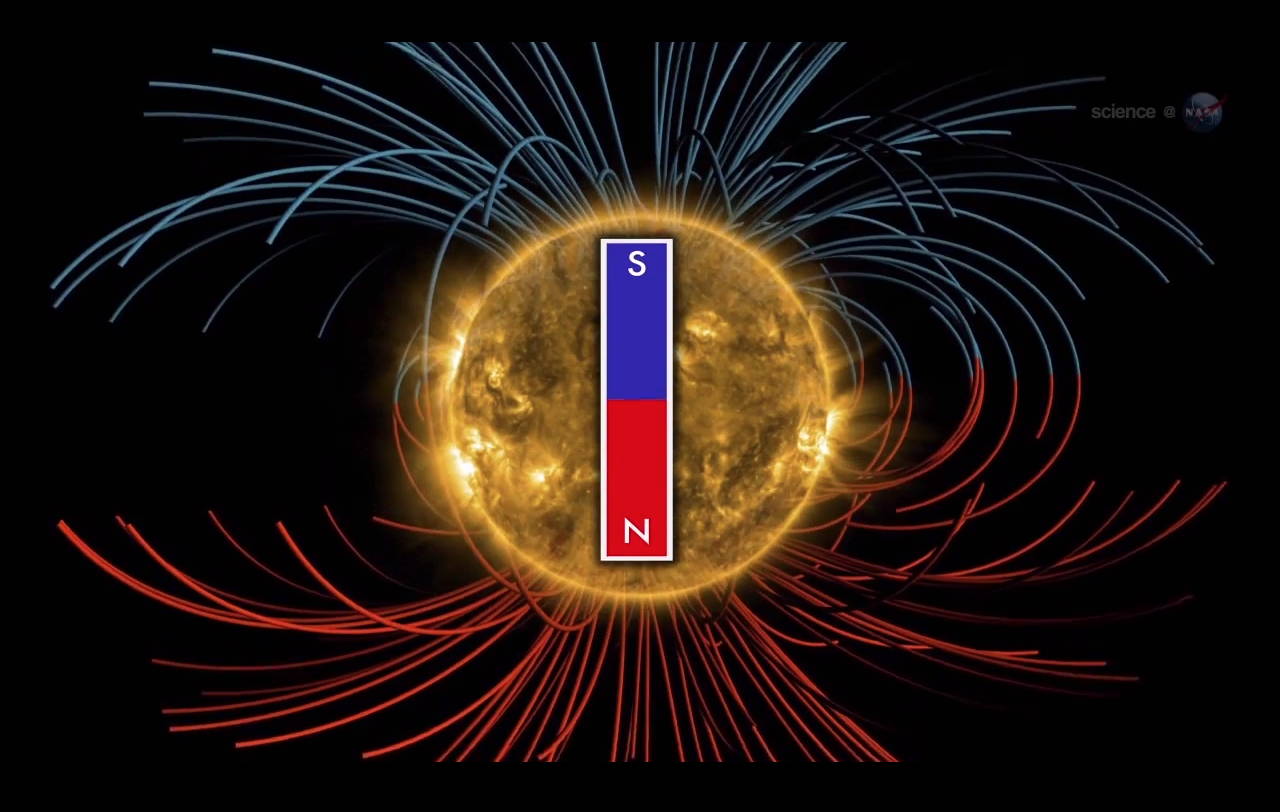

The sun's magnetic field will reverse its polarity three or four months from now, researchers say, just as it does every 11 years at the peak of the solar activity cycle. While solar physicists know enough about this strange phenomenon to predict when it will occur, its ultimate causes remain mysterious.

"That gets into the whole [solar] cycle, and wondering what that is," Stanford University solar physicist Phil Scherrer told SPACE.com. "We still don't have a really self-consistent mathematical description of what's happening. And until you can model it, you don't really understand it — it's hard to really understand it." [Solar Magnetic Field Will Soon Flip (Video)]

During the field flip, the sun's polar magnetic fields will weaken all the way down to zero, then bounce back with the opposite polarity. The shift is closely tied to the activity of sunspots (also known as active regions), said fellow Stanford solar physicist Todd Hoeksema, who runs the university's Wilcox Observatory.

"The magnetic field from active regions makes its way toward the poles and eventually causes the reversal," Hoeksema told SPACE.com.

But researchers lack a deep understanding of the process.

"What it really depends on is where the magnetic fields come from," Hoeksema said. "Are there going to be many sunspots? And are the sunspots going to contribute to the magnetic field of the pole, or are they going to kind of cancel locally? That question we don't yet know how to answer."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The field reversal is nothing to worry about, Scherrer and Hoeksema stress; it won't spawn any big solar storms or otherwise cause problems for people here on Earth. Its chief effect on us, in fact, will likely be beneficial.

The sun's slowly rotating magnetic field induces an electric current in a huge surface that extends from our star's equator far out into the solar system. During field reversals, this "current sheet" gets wavier, providing a better barrier against galactic cosmic rays — super-energetic particles that can damage satellites and harm astronauts orbiting the planet.

After the flip, scientists will keep a close eye on the sun's magnetic field for two years or so. If it bounces back strongly within that time, they say, the next 11-year solar cycle will likely be a relatively active one. If the buildup is sluggish, by contrast, we're probably in for another wimpy cycle, like the current Solar Cycle 24.

Another weak field recovery would continue a trend that solar physicists are scratching their heads about, Hoeksema said.

"The polar fields have been getting weaker and weaker over the last 30 years, and so also the following sunspot cycles have been getting weaker over the years," he said. "We don't really understand why, or even if that's the cause or if they're both symptoms of the same thing. It's a fun and interesting puzzle."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.