The revolutionary planet-hunting activities of NASA's prolific Kepler space telescope have come to an end.

NASA has given up hope of restoring the Kepler spacecraft to full health and is now attempting to determine what the observatory can accomplish in its compromised state, agency officials announced today (Aug. 15).

"We are now moving on to the next phase of Kepler's mission, because that's what the data requires us to do," Paul Hertz, director of NASA's astrophysics division, told reporters during a press conference today. "This is not the last you'll hear from Kepler. There's a huge amount of data collected that we'll continue to analyze." [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

Balky wheels

The $600 million Kepler mission launched in March 2009 on a 3.5-year prime mission to determine how commonly Earth-like planets occur around the Milky Way galaxy.

Kepler detects exoplanets by noting the tiny brightness dips caused when these worlds cross in front of, or transit, their parent stars. The observatory needs three working reaction wheels — gyroscope-like devices that maintain Kepler's position in space — to do this precision work.

Kepler had four of these wheels when it launched — three for immediate use and one spare. But one wheel, known as number 2, failed in July 2012. And then wheel four conked out on May 11 of this year, halting the spacecraft's planet hunt.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mission engineers have since managed to get those two malfunctioning wheels spinning again, but both of them still exhibit too much friction to support Kepler's fine-pointing work. So the observatory's original mission is over, officials said today.

"We do not believe that we can recover three-wheel operations, or Kepler's original science mission," Hertz said.

Sending astronauts out to fix Kepler, as was done five times with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, is not an option. That's because Kepler orbits the sun rather than Earth and is currently millions of miles from our planet.

Looking ahead

The focus has now shifted to examining what Kepler can accomplish with just two healthy wheels and its thrusters, Hertz added.

To that end, NASA is conducting two separate studies: an engineering assessment to see what the spacecraft is capable of, and a science study to determine if a modified mission is worth funding. (It currently costs about $18 million per year to operate the telescope.)

Both studies are due in the fall, Hertz said.

"NASA may use a senior review to help us prioritize a two-wheel Kepler mission against the continued operation of other NASA astrophysics missions," he said. "Only after weighing these considerations will NASA be in a position to make a decision on the future of Kepler operations."

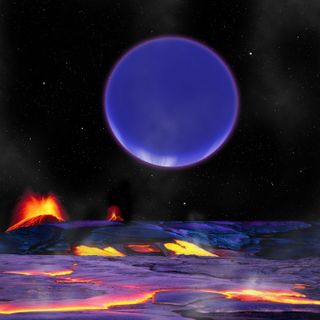

There are a variety of possible uses for Kepler in the future, mission scientists say. The observatory could scan the heavens for asteroids, comets and supernova explosions, for example. And it may still be able to detect huge alien planets using a technique called gravitational microlensing. (In this method, astronomers watch what happens when a massive object passes in front of a star; the closer object's gravitational field bends and magnifies the star's light, acting like a lens.)

But it's still to soon to tell which, of any, of these missions will pan out.

"Until we have analyzed the full capability of the mission and we have looked at what the requirements are in terms of guidance, we really have no way no way of knowing which of these missions would be practical," said Kepler principal investigator Bill Borucki, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif.

Lots of discoveries to come

Kepler has detected 3,548 candidate planets to date, 135 of which have been confirmed by follow-up observations. Mission scientists expect more than 90 percent of the observatory's finds will end up being the real deal.

And there will be more discoveries to come, whatever Kepler ends up doing in the future. It will take several more years to pore through all of the observatory's data, Borucki said.

"We expect hundreds, maybe thousands of new planet discoveries, including the long-awaited Earth-size planet orbiting a star as hot as our sun — so a very sun-like star," he said.

Kepler outlasted its prime mission lifespan of 3.5 years, and it should be able to accomplish its main goal despite the reaction-wheel failures, Borucki added.

"In the next two years, when we complete this analysis, we'll be able to answer the question that inspired the Kepler mission: Are Earths common or rare in our galaxy?" he said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.