Every August, when many people are vacationing in the country where skies are dark, the best-known meteor shower makes its appearance. The annual Perseid meteor shower, as it is called, promised to put on an above average display this year.

The event is also known as "The Tears of St. Lawrence."

Laurentius, a Christian deacon, is said to have been martyred by the Romans in 258 AD on an iron outdoor stove. It was in the midst of this torture that Laurentius cried out: "I am already roasted on one side and, if thou wouldst have me well cooked, it is time to turn me on the other."

The saint's death was commemorated on his feast day, Aug. 10. King Phillip II of Spain built his monastery place the "Escorial," on the plan of the holy gridiron. And the abundance of shooting stars seen annually between approximately Aug. 8 and 14 have come to be known as St. Lawrence's "fiery tears."

Behind the tears

We know today that these meteors are actually the dross of the Swift-Tuttle comet. Discovered back in 1862, this comet takes approximately 130 years to circle the Sun. With each pass, it leaves fresh debris -- mostly the size of sand grains with a few peas and marbles tossed in.

Every year during mid-August, when the Earth passes close to the orbit of Swift-Tuttle, the bits and pieces ram into our atmosphere at approximately 37 miles per second (60 kps) and create bright streaks of light.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

According to the best estimates, in 2004 the Earth is predicted to cut through the densest part of the Perseid stream sometime around 7 a.m. ET on Thursday, Aug. 12. Activity could be high for a few hours on either side of that time.

The late-night hours of Wednesday, Aug. 11, on through the first light of dawn on the morning holds the promise of seeing a very fine Perseid display. The bright light of a Full Moon almost totally wrecked last year's shower, but this year it will be a lovely crescent, about 3? days before New phase. Moreover, it will not rise until around 2:30 a.m. local daylight time on the morning of the12th, hovering to the east of brilliant Venus.

Possible bonus

Comet Swift-Tuttle made its most recent appearance nearly a dozen years ago, in December 1992. Its orbit is highly elongated, taking roughly 130 years to make one trip around the Sun.

For several years before and after its 1992 return, the Perseids were a far more prolific shower, appearing to produce brief outbursts of as many as several hundred meteors per hour, many of which were dazzlingly bright and spectacular. The most likely reason was that the Perseids parent comet was itself passing through the inner solar system and that the streams of Perseid meteoroids in the comet's vicinity were larger and more thickly clumped together.

In recent years, with the comet now far back out in space, Perseid activity has apparently returned to normal. However, two well-known meteor astronomers now suggest that the 2004 Perseids may yet provide some surprises.

Esko Lyytinen of Finland and Tom Van Flandern of Washington, D.C. have made calculations concerning extradense filaments of dust trailing well behind Comet Swift-Tuttle. From their studies they conclude that the Perseids may put on unusually strong, albeit brief display this year.

Lyytinen and Van Flandern believe that this year the Earth will pass through a trail of debris shed by Comet Swift-Tuttle during its 1862 visit. The closest that Earth will come to the center of this debris trail will be 123,000 miles (200,000 kilometers).

The time of the closest approach should be 4:50 p.m. ET (20:50 GMT) on Aug. 11 and could last about 40 minutes, favoring observers in Eastern Europe, eastern North Africa eastward to central Russia, India, and western China. Unfortunately, if a sudden bevy of Perseids materializes, North Americans would miss out, since it happen during local afternoon hours. "I would expect a short peak of a few hundred meteors per hour, though they should be mostly faint," said Lyytinen.

Viewers should keep in mind that meteor forecasting is a tricky business, however.

What to expect

A very good shower will produce about one meteor per minute for a given observer under a dark country sky. Any light pollution or moonlight considerably reduces the count.

The August Perseids are among the strongest of the readily observed annual meteor showers, and at maximum activity nominally yield 50 or 60 meteors per hour. However, observers with exceptional skies often record even larger numbers. Typically during an overnight watch, the Perseids are capable of producing several bright, flaring and fragmenting meteors, which leave fine trains in their wake.

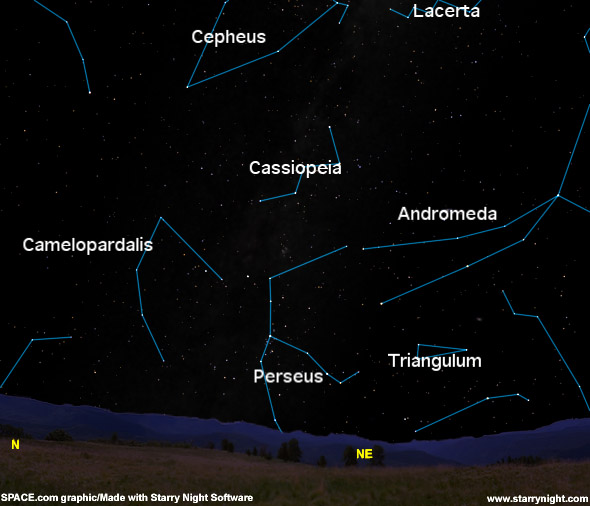

On the night of shower maximum, the Perseid radiant is not far from the famous "Double Star Cluster" of Perseus. Low in the northeast during the early evening, it rises higher in the sky until morning twilight ends observing. Perseid meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but if traced backward, they all point toward Perseus, which is know as the shower's radiant.

Shower members appearing close to the radiant have foreshortened tracks; those appearing farther away are often brighter, have longer tracks, and move faster across the sky. About five to 10 of the meteors seen in any given hour will not fit this geometric pattern, and may be classified as sporadic or as members of some other (minor) shower.

As with meteor activity in general, Perseid activity increases sharply in the hours after midnight, so plan your observing times accordingly. We are then looking more nearly face-on into the direction of the Earth's motion as it orbits the Sun, and the radiant is also higher up. [See a Graphic]

Making a meteor count is as simple as lying in a lawn chair or on the ground and marking on a clipboard whenever a "shooting star" is seen. Watching for the Perseids consists of lying back, gazing up into the stars, and waiting. It is customary to watch the point halfway between the radiant (which will be rising in the northeast sky) and the zenith (the imaginary point directly overhead) though its fine for your gaze to wander.

Counts should be made on several nights before and after the predicted maximum, so the behavior of the shower away from its peak can be determined. Usually, good numbers of meteors should be seen on the preceding and following nights as well. The shower is generally at one-quarter strength one or two nights before and after maximum.

| Any Danger? Many years ago, a phone call came into New York's Hayden Planetarium. The caller sounded concerned about a radio announcement of an upcoming Perseid display and wanted to know if it would be dangerous to stay outdoors on the night of the peak of the shower (perhaps assuming there was a danger of getting hit). These meteoroids, however, are no bigger than sand grains or pebbles, have the consistency of cigar ash and are consumed many miles above our heads. The caller was passed along to the Planetarium's Chief Astronomer who commented that there are only two dangers from Perseid watching: getting drenched with dew and falling asleep! -- Joe Rao | Any Danger? | Many years ago, a phone call came into New York's Hayden Planetarium. The caller sounded concerned about a radio announcement of an upcoming Perseid display and wanted to know if it would be dangerous to stay outdoors on the night of the peak of the shower (perhaps assuming there was a danger of getting hit). These meteoroids, however, are no bigger than sand grains or pebbles, have the consistency of cigar ash and are consumed many miles above our heads. The caller was passed along to the Planetarium's Chief Astronomer who commented that there are only two dangers from Perseid watching: getting drenched with dew and falling asleep! -- Joe Rao |

| Any Danger? | ||

Many years ago, a phone call came into New York's Hayden Planetarium. The caller sounded concerned about a radio announcement of an upcoming Perseid display and wanted to know if it would be dangerous to stay outdoors on the night of the peak of the shower (perhaps assuming there was a danger of getting hit). These meteoroids, however, are no bigger than sand grains or pebbles, have the consistency of cigar ash and are consumed many miles above our heads. The caller was passed along to the Planetarium's Chief Astronomer who commented that there are only two dangers from Perseid watching: getting drenched with dew and falling asleep! -- Joe Rao |

- The Dangers of Meteors

A few Perseids can be seen as much as two weeks before and a week after the peak, though casual viewers may not find meteor watching very rewarding on such nights. The extreme limits of the Perseids are said to extend from July 17 to Aug. 24.

Take a picture

The Perseids are also an excellent meteor display to attempt to photograph. Meteor photography is popular and can be carried out with practically any camera. However, the chance of recording a meteor is enhanced by using a fast lens (f 2.8 or better) and ultrafast film (ISO 400 to 1600). It makes no difference whether the camera is clock-driven or fixed on a tripod.

In a dark sky, exposures of 10 to 20 minutes long can be made, but should be kept much shorter if background light threatens to fog the film. Slight moonlight, twilight or city glow can be tolerated, as they have little to do with the efficiency of a particular lens-film combination in recording bright meteors.

A successful photograph has many added values if an observer has witnessed and described the same meteor. Also, the chance of obtaining a good meteor picture can be increased by pointing the camera well away from the radiant.

- Meteor Observing Tips

- Photographing Meteor Showers

- Scary Sounds of Meteors

- Comets, Meteors & Myth

- How Meteor Showers Work

Starry Night software brings the universe to your desktop. Map the sky from your location, or just sit back and let the cosmos come to you.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.