Happy Birthday Spitzer! NASA's Infrared Space Telescope Hits 10-Year Mark

NASA's infrared eye on the universe, the Spitzer Space Telescope, marks its 10th year in space this Sunday (Aug. 25), and it's still going strong.

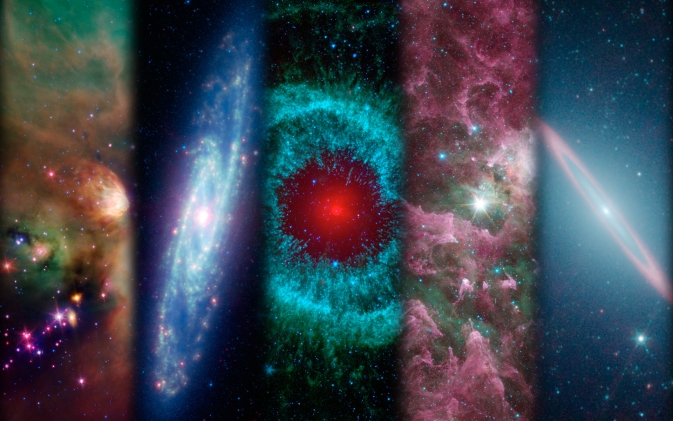

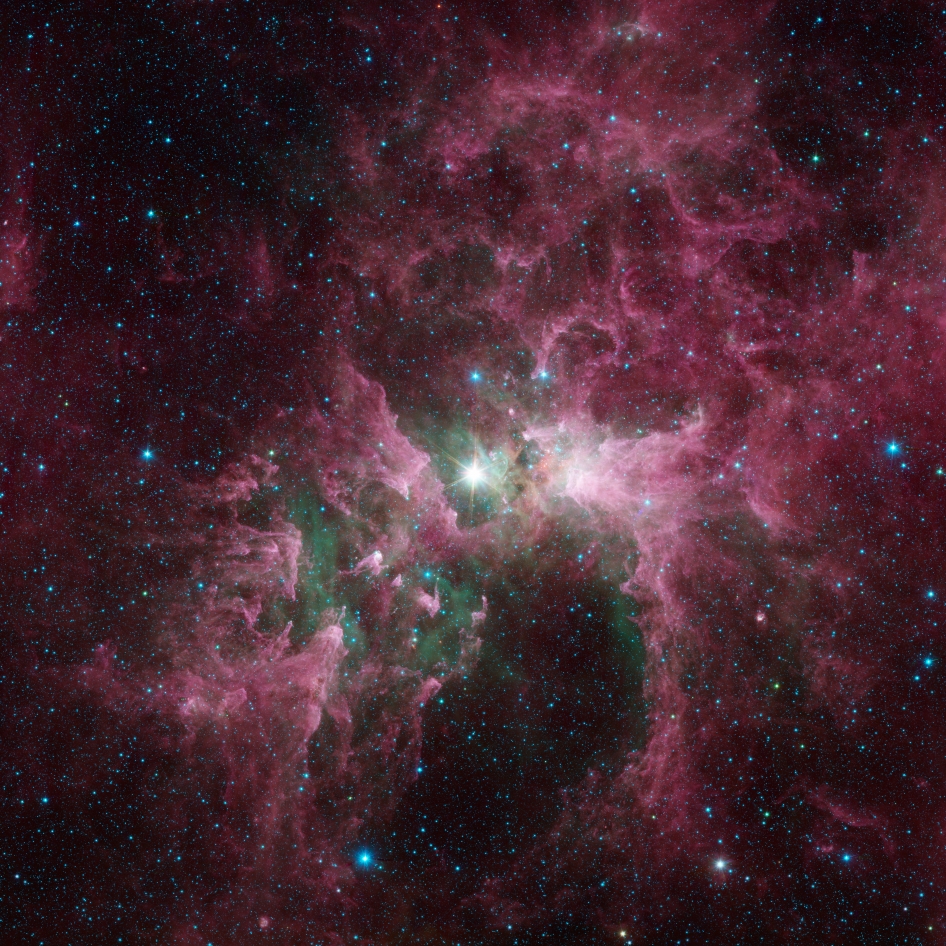

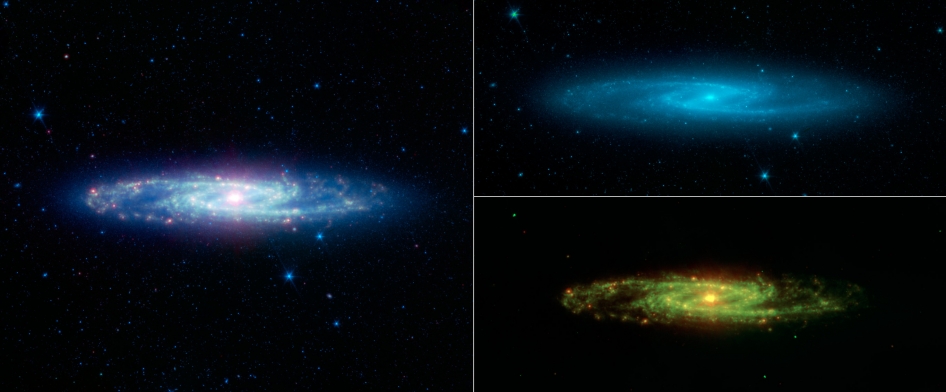

The Space Telescope observes the cosmos in non-visible infrared light, which allows it to see many aspects of the universe, such as dim, cold, faraway and dusty objects, which would otherwise be invisible.

In its decade of observing, Spitzer has made many headline finds, including spotting the first light from a planet beyond our solar system, and discovering the largest ring around Saturn. This ring is a thin band of ice and dust that releases such paltry light it can only been seen by the glow of its heat, which is detectable in the infrared band. [Gallery: The Infrared Universe Seen by Spitzer Telescope]

"I always knew Spitzer would work, but I had no idea that it would be as productive, exciting and long-lived as it has been," Spitzer project scientist Michael Werner of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who helped conceive the mission, said in a statement. "The spectacular images that it continues to return, and its cutting-edge science, go far beyond anything we could have imagined when we started on this journey more than 30 years ago."

The $800 million telescope was in the works for decades before it finally launched from Cape Canaveral, Fla., on Aug. 25, 2003. Originally called the Space Infrared Telescope Facility, it was renamed Spitzer after it reached space, in honor of the American astronomer Lyman Spitzer.

Spitzer had been one of the first proponents of space-based observatories, which can watch the heavens from beyond the blurring light of Earth's atmosphere, and can see wavelengths of light blocked by the protective gaseous cocoon around our planet.

Spitzer is one of NASA's series of "Great Observatories" designed to scan the sky in wavelengths running the gamut of the electromagnetic spectrum. The other Great Observatories are the Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory — the only one of the four no longer operating.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The majority of our Great Observatory fleet is still up in space, each with its unique perspective on the cosmos," Paul Hertz, Astrophysics Division director at NASA headquarters in Washington, said in a statement. "The wisdom of having space telescopes that cover all wavelengths of light has been borne out by the spectacular discoveries made by astronomers around the world using Spitzer and the other Great Observatories."

Though Spitzer can't do everything it once did — in 2009 it ran out of the coolant needed to chill its sensitive longer-wavelength instruments — it still has its work cut out for it. NASA scientists plan to use the instrument to study asteroids that are candidates for a major mission planned for the future.

NASA aims to use a robotic spacecraft to capture a small asteroid and drag it in toward Earth, where astronauts can go visit it to inspect its surface and collect samples to return to ground labs. Spitzer will be used to study possible asteroid targets for the mission. First up is the near-Earth asteroid named 2009 DB, which the telescope will turn its eyes on in October.

"President Obama's goal of visiting an asteroid by 2025 combines NASA’s diverse talents in a unified endeavor," said John Grunsfeld, NASA's associate administrator for science in Washington. "Using Spitzer to help us characterize asteroids and potential targets for an asteroid mission advances both science and exploration."

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.