Stargazers will be able to spot a fierce dragon in the evening sky this week.

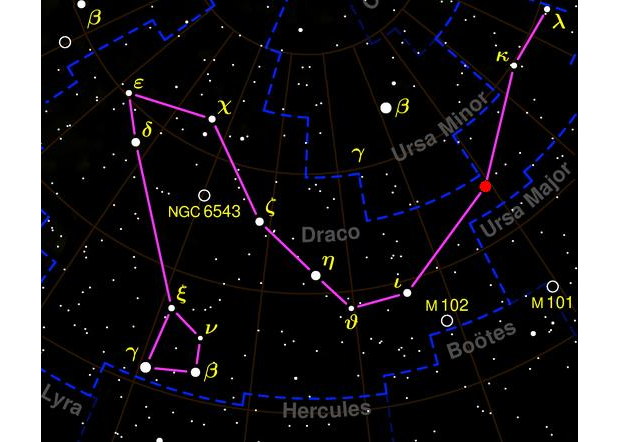

Draco — the celestial dragon — is a large, albeit dim, constellation. He is circumpolar — that is, the constellation always remains above the horizon, never rising or setting for skywatchers at most midnorthern latitudes. But right now is the best evening season for tracing out the windings of this mythical beast’s snakelike body. This week, between 8:30 p.m. and 9:00 p.m. local daylight time, he appears to pass between both the Little Dipper and Big Dipper, with his head raised high above the North Star Polaris, almost to the overhead point (called the zenith).

The dragon’s head is the most conspicuous part of Draco: an irregular quadrangle, not quite half the size of the Big Dipper’s bowl. You can find it situated about 12 degrees (10 degrees is roughly equal to a clenched fist held at arm’s length) to the north and west of the brilliant blue-white star, Vega — the brightest of the three stars that make up the Summer Triangle. [Amazing Night Sky Photos for August (Gallery)]

An old dragon

Draco is a very ancient grouping of stars. Supposedly, Draco was sent into battle against the goddess of wisdom, Athene, who faced the dragon attired in heavy armor with her magic shield at her side.

Grabbing onto Draco at his tail, she swung him high above her head and hurled him high into the sky. As he soared away, his body kept spinning so that he ultimately became coiled into a sort of twisted shape.

"He struck the arch of the sky at the very spot around which the firmament itself revolved, and before he could even uncurl, he was caught in the axis of heaven," Peter Lum writes of Draco in his book "The Stars in Our Heaven" (Pantheon Books, 1948). "There he lies still, now fallen peaceably asleep, his snaky coils inextricably entangled with the North Pole, and as the northern sky turns on its axis he turns with it."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A fiery star and cosmic headlights

In the stars, Draco coils around Polaris. The brightest star that makes up the constellation is Eltanin, in Draco’s head, a second magnitude star, shining with an orange tinge; perhaps this is where fire was thought to emanate from the cosmic dragon. A number of temples in ancient Egypt were apparently oriented toward this star.

The faintest of the four stars in the quadrangle is Nu Draconis, a wonderful double star for very small telescopes. The two stars are practically the same brightness, both appearing just a trifle brighter than fifth magnitude and separated by just over one arc minute (or about 1/30 the apparent diameter of the full moon).

I first stumbled across Nu all too many years ago as a teenager in the Bronx, using low power on a 4 1/4-inch Newtonian reflecting telescope. I likened the stars to a pair of tiny headlights.

A past (and future) North Star

Although Polaris is considered the North Star, it has not always been thought of as the cosmic signpost it is today.

The pole of the heavens is moving slowly among the constellations of the northern sky owing to a movement of the Earth cause by the sun and moon known as "precession." The moon and sun pull on the bulging equator of the Earth, creating a double attraction that causes the planet to wobble slightly, similar to the motion of a spinning top slowing down.

While the tilt of the axis to the Earth’s orbit remains the same (tilted 23.5 degrees from the equator), the axis itself moves in a funnel-shaped motion, completing one rotation in about 25,800 years. This time span — one complete wobble — is called a "great" or "platonic" year.

Located in Draco’s tail is the faint star Thuban. During the third millennium, B.C., the Earth’s axis was pointed almost directly at this star. As such, Thuban was the North Star when the pyramids were being built, some 5,000 years ago.

Thuban was nearest to the North Pole of the sky in about 2830 B.C. It then shined almost motionless in the north, near to where the current North Star, Polaris, now appears. Look roughly midway between the bowl of the Little Dipper and the star Mizar (where the Big Dipper’s handle bends) to find the former North Star.

Thanks to the oscillating motion of precession, Thuban will once again be the North Star some 20,000 years from now.

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing picture of any night sky sight that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to Managing Editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.