Evidence of water spotted on the moon's surface by a sharp-eyed spacecraft likely originated from an unknown source deep in the lunar interior, scientists say.

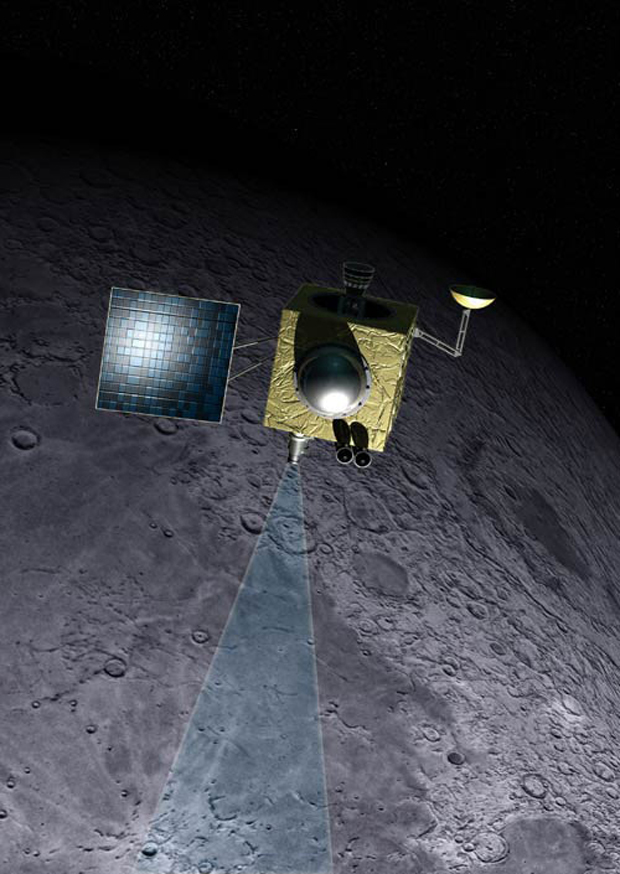

The find — made by NASA's Moon Mineralogy Mapper instrument aboard India's Chandrayaan-1 probe — marks the first detection of such "magmatic water" from lunar orbit and confirms analyses performed recently on moon rocks brought to Earth by Apollo astronauts four decades ago, researchers said.

"Now that we have detected water that is likely from the interior of the moon, we can start to compare this water with other characteristics of the lunar surface," study lead author Rachel Klima, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md., said in a statement. [Water on the Moon: The Search in Photos]

"This internal magmatic water also provides clues about the moon's volcanic processes and internal composition, which helps us address questions about how the moon formed, and how magmatic processes changed as it cooled," Klima added.

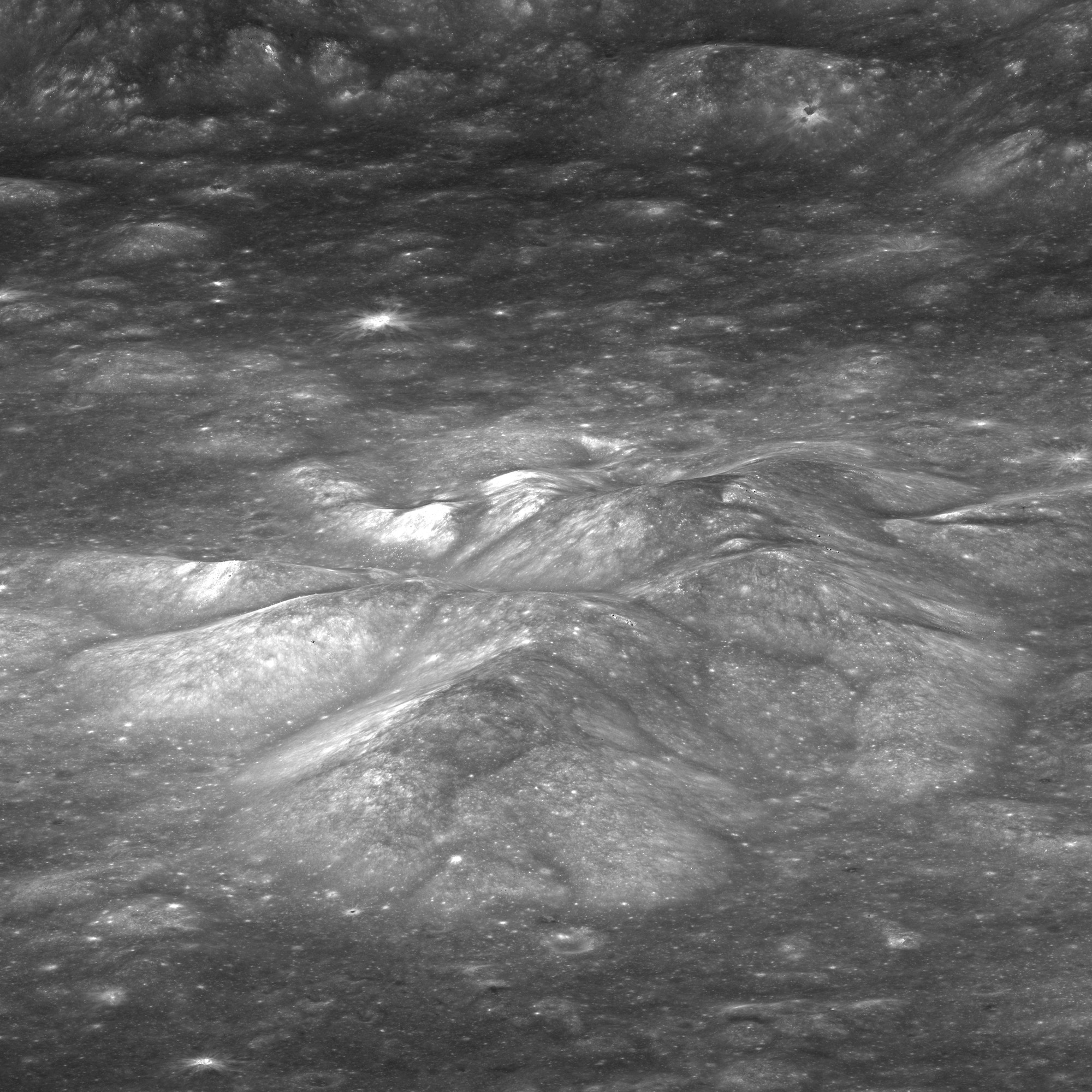

The Moon Mineralogy Mapper, or M3, imaged a 37-mile-wide (60 kilometers) impact crater near the lunar equator called Bullialdus, whose central peak is composed of a type of rock that forms when magma is trapped deep underground. This rock was excavated and exposed by the impact that formed Bullialdus, Klima said.

"Compared to its surroundings, we found that the central portion of this crater contains a significant amount of hydroxyl — a molecule consisting of one oxygen atom and one hydrogen atom — which is evidence that the rocks in this crater contain water that originated beneath the lunar surface," she said.

The solar wind — the stream of charged particles flowing from the sun — can create thin layers of water molecules when it strikes the lunar surface. Indeed, M3 found such water near the poles when it mapped the moon's surface in 2009.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But scientists think the solar wind can only form significant quantities of surface water at high latitudes, ruling out this process as the source of the stuff in the more equatorial Bullialdus Crater.

The new findings, which are detailed in the Aug. 25 edition of the journal Nature Geoscience, further fuel scientists' growing realization that the moon is not the bone-dry place it was long assumed to be.

There are those 2009 observations by the M3 instrument, for example. Also in 2009, NASA's Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite mission smashed an impactor into the moon's permanently shadowed Cabeus Crater, throwing up a huge plume of water vapor and ice particles.

Scientists now think many polar craters on the moon harbor large amounts of water ice — so much, in fact, that firms such as the Shackleton Energy Company and Moon Express aim to mine this ice and turn it into rocket propellant to help fuel humanity's expansion out into the solar system.

Chandrayaan-1 was India's first robotic moon probe. The spacecraft launched in October 2008 and sent an impactor into the lunar surface a month later, making India the fourth nation to plant its flag on the moon. Chandrayaan-1 continued making science observations from lunar orbit until August 2009, when it abruptly stopped communicating with Earth.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.