First 'Trojan' Asteroid Companion of Uranus Found

Astronomers have discovered an unexpected, novel kind of triangle in the sky — one whose points are the sun, Uranus and the first "Trojan asteroid" ever seen near the tilted planet.

The discovery of the Trojan asteroid for Uranus suggests Uranus and Neptune could have far more such asteroid companions than previously thought, scientists say.

In astronomy-speak, objects that share their orbit with a planet — but do not collide with the world — are known as Trojans. Such objects have been seen around several planets in our solar system, including the Earth, but the newfound asteroid 2011 QF99 near Uranus is the first ever seen for that planet. [Photos of Uranus, the Tilted Planet]

Trojan asteroids explained

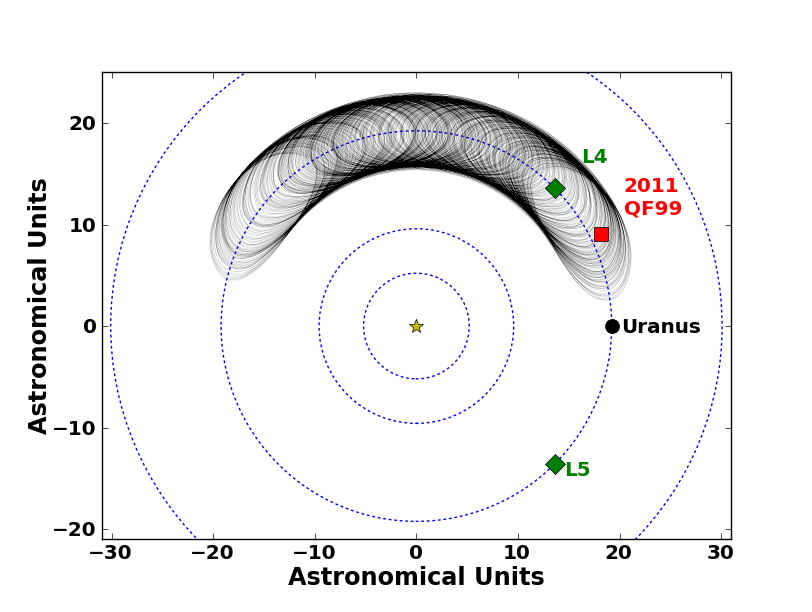

To picture, say, Earth's Trojan asteroid, imagine the sun and Earth as being two points in a triangle whose sides are equal in length. The other point of such a triangle is known as a Trojan point, or a Lagrangian point, named after the mathematician who discovered them. At such a point, the gravitational attraction of the sun and Earth essentially balances out, meaning they are relatively stable points for asteroids or other objects.

The sun and Earth have two Trojan points, one leading ahead of Earth, known as the L-4 point of the system, and one trailing behind, its L-5 point. The sun and other planets have Lagrangian points also, with asteroids seen at those the sun shares with Jupiter, Neptune and Mars.

Scientists thought the Trojan points of Uranus, the seventh planet from the sun, were too unstable to host asteroids. Now astronomers using the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope have discovered the first Trojan for Uranus.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In 2011 and 2012, the researchers were tracking objects in the regions of the giant planets for 17 months to better model the evolution of the outer solar system.

"Our search was focused on finding Neptunian Trojans and trans-Neptunian objects," study lead author Mike Alexandersen, an astronomer at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, told SPACE.com. "One is always surprised and excited to find something other than what one was expecting and searching for."

New asteroid around Uranus

The astronomers discovered asteroid 2011 QF99, a ball of rock and ice, leading Uranus in the planet's orbit. The body, which is about 36 miles (60 kilometers) wide, resembles an asteroid in appearance but probably is more like a comet in composition.

This asteroid is about 19 astronomical units from the sun — that is, 19 times that between the Earth and sun. The Earth is typically about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) from the sun. Altogether, the sun, Uranus and this asteroid form a triangle whose sides are currently about 1.7 billion miles (2.8 billion km) long.

Anomalies in the orbital trajectory of asteroid 2011 QF99 suggest it is a temporary companion of Uranus, originally coming from the outer regions of the solar system. The scientists calculate it will share its orbit with the planet for just 70,000 years before escaping this Trojan point. In at most 1 million years, this object will rejoin the flood of planet-crossing bodies known as Centaurs from which it came.

Trojan asteroids across the solar system

Based on this new data, the researchers calculate that about 0.1 percent of all the asteroids and comets 6 to 34 astronomical units from the sun are Uranian Trojans at any given time, meaning Uranus has a virtually constant population of companions. They also estimated about 1 percent of all the asteroids and comets beyond Jupiter's orbit are Neptunian Trojans.

"This might trigger a wave of searches for Uranian Trojans — now that people know they exist, it will be easier to get telescope time to search for them than when it was thought unlikely to find anything," Alexandersen said.

These temporary Trojans reveal objects traveling inward from the outer fringes of the solar system "aren't just being scattered all over the place in a seemingly chaotic fashion," Alexandersen said. "There are in fact these small reservoirs where objects get temporarily stuck, just like how sticks flowing down a river can sometimes get temporarily stuck circling in eddies or calm pools before finally escaping to continue down the river."

The scientists detailed their findings in the Aug. 30 issue of the journal Science.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us