NASA's Voyager 1 probe won't rest on its laurels after becoming the first manmade object ever to reach interstellar space.

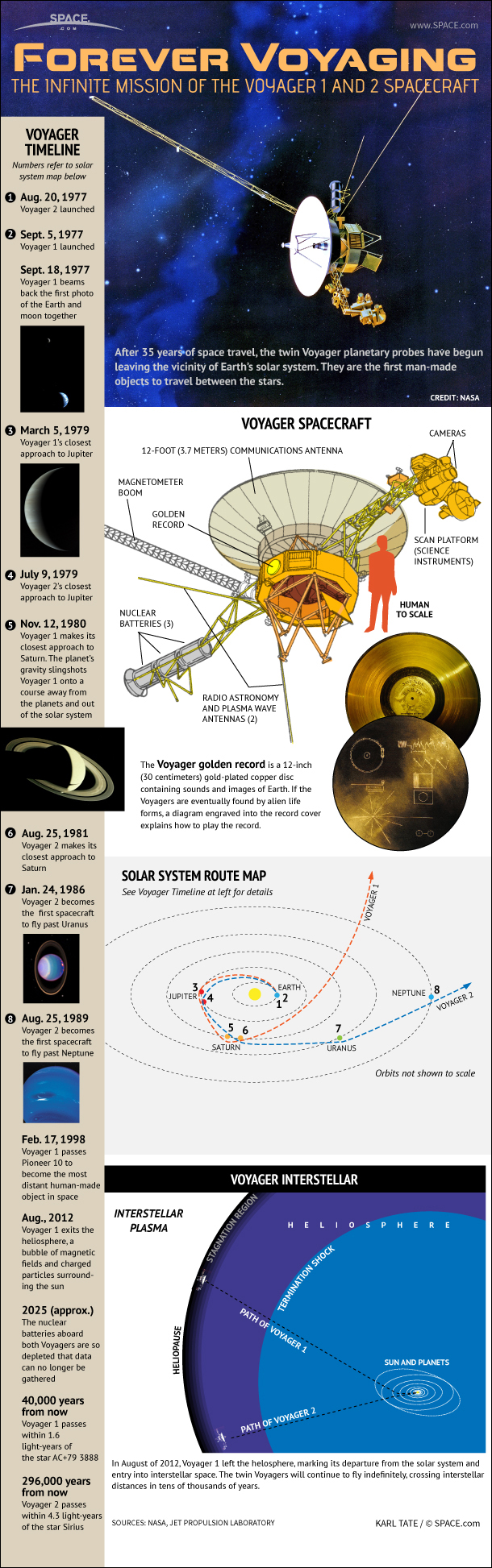

Voyager 1 arrived in interstellar space in August 2012 after 35 years of spaceflight, researchers announced Thursday (Sept. 12). While this milestone is momentous enough in its own right, it also opens up a new science campaign whose potential already has scientists salivating.

"For the first time, we're actually going to be able to put our hands in the interstellar medium and ask what it does and what characteristics it possesses," Gary Zank, director of the Center for Space Plasma and Aeronomic Research at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, told reporters Thursday. "It's a tremendous opportunity." [Voyager 1 Sailing Through the Interstellar Void (Video)]

Into the unknown

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, launched a few weeks apart in 1977 to study Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, as well as the moons of these outer planets.

The probes completed this historic "grand tour" in 1989, then embarked on a quest to study the outer reaches of the solar system and beyond.

Voyager 1 finally popped free of the heliosphere — the huge bubble of charged particles and magnetic fields that the sun puffs out around itself — on or around Aug. 25, 2012, becoming humanity's first envoy to the vast realms between the stars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This is truly a remarkable achievement," Zank said. "We've exited the material that's created by the sun, and we're in a truly alien environment. The material in which Voyager finds itself is not created by the sun; it's created, in fact, by our neighboring stars, supernova remnants and so forth."

Many discoveries to come

This new vantage point should yield big scientific dividends, Zank added. For example, Voyager 1 should now help researchers get a much better look at galactic cosmic rays, charged particles accelerated to incredible speeds by far-off supernova explosions.

Observations of galactic cosmic rays made from within the heliosphere are not ideal, since the solar wind tends to affect these high-energy particles substantially.

"Being outside the heliosphere allows us an opportunity to, in a sense, look at the undiluted galactic cosmic ray spectrum," Zank said. "That will tell us a great deal more about the interstellar medium at very distant locations. It'll tell us about how the galactic cosmic rays propagate through this very complicated interstellar medium."

Voyager 1 should also be able to shed light on the nature of the instellar medium, and how material from other stars flows around the heliosphere, researchers said.

"Now we will be able to understand and measure and observe that interaction, which is a very important part of how the sun interacts with what's around it," Voyager chief scientist Ed Stone, a physicist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, told SPACE.com.

In short, reaching interstellar space does not mark the end of the road for Voyager 1, which should be able to continue gathering data for a dozen more years as long as nothing too important breaks down. (The probe's dwindling power supply will force the mission team to turn off the first instrument in 2020, and all of Voyager 1's science gear will be shut down by 2025.)

"This mission is not over," said Voyager project manager Suzanne Dodd, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Many, many more discoveries are out there, yet to come."

.Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.