Mothballed Satellite Sits In Warehouse, Waits For New Life

The long-grounded Deep Space Climate Observatory may berevived for an assignment very different from the controversial mission thatwas cancelled for its infamous mix of politics and science.

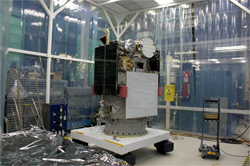

NASA, NOAAand the U.S. Air Force completed a comprehensive study last month to determinethe feasibility of finally launching the refrigerator-sized satellite, whichhas been confined to a lonely corner of a Maryland warehouse for seven years.

The agenciesare discussing adapting the DSCOVRspacecraft for a new mission to monitor solar wind and space weather from theL1 libration point, a site 1 million miles away where the pull of gravity fromthe sun and Earth is equal.

Althoughengineers say the spacecraft is healthy after its lengthy storage, DSCOVR's newplans will probably depend on NOAA's budget over the next few years.

NOAA and theAir Force have already paid NASA to remove DSCOVR from its white storage crateand begin testing at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

"Wehave paid NASA to do a study to tell us if DSCOVR as a spacecraft is stillflyable," said Gary Davis, director of the Office of SystemsDevelopment at NOAA's Satellite and Information Service.

The testingbegan in November with the power-up of DSCOVR and a set of space environmentsensors known as PlasMag. DSCOVR's Earth science instruments were not turnedon.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The checksare helping officials estimate the cost of revamping the satellite for a newmission and launching it on an expendable rocket.

NASAdelivered a report to NOAA last month outlining the results of the study,including the spacecraft's health. NOAA officials are still analyzing theassessment, an agency spokesperson said.

A team ofabout 30 employees checked the satellite's systems and conducted magneticcleanliness tests. DSCOVR's solar arrays were also successfully deployed, andengineers are currently testing the power-producing panels in a vacuum chamberat Goddard.

"Thefirst time we opened up the spacecraft, it worked perfectly," said JoeBurt, a NASA official overseeing the testing. "It was like it had justbeen asleep."

The focus ofthe new would-be mission, which is still unnamed, would be to measure solarwind particles and their effects on the environment around Earth.PlasMag and a solar coronal mass ejection sensor would be likely payloads, butspecifics have not yet been finalized.

Data fromthe redefined DSCOVR mission would be similar to science produced by theAdvanced Composition Explorer and the Wind space observatory, which are 11years old and 14 years old, respectively.

PlasMagwould provide a 30-fold improvement in temporal resolution over ACE and Wind,according to scientists.

The solarwind data would be used for operational space weather forecasting by NOAA andthe Air Force Weather Agency, according to an Air Force spokesperson.

Officialshave not determined the fate of DSCOVR's Earth science instruments, but themission's principal investigator said a decision to remove the climateinstruments would be "appalling."

FranciscoValero, a researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego,still leads a team of scientists in charge of DSCOVR's original scienceobjectives.

Valero saidthe cost of launching DSCOVR's full set of instruments, which includes payloadsdesigned to monitor the solar wind, would not be much different than the costof flying a new instrument package geared only toward space environmentstudies.

"Thetotal cost of the instruments, the science, and the support that will benecessary is about 10 or 15 percent of the total cost (of the mission),"Valero said. "The lost opportunity for science and the waste of taxpayers'money are unconscionable."

The currentDSCOVR study was commissioned under the Bush administration, and Valero isappealing to senior government officials in an attempt to salvage the mission'sEarth science goals.

"Allthat needs to be done is to launch the satellite as it is now," Valerosaid. "Everything is on there. The solar instruments are on. The Earthscience instruments are already bolted on the satellite. If they don't startworking and spending money to remove things, that would be wonderful."

Valero saidhe hopes the Obama administration will proceed with DSCOVR as is, but keyleadership positions at NASA and NOAA remain unfilled. President Obama has notnamed a new NASA administrator, and NOAA Administrator nominee Jane Lubchencois still awaiting Senate confirmation.

Lubchencodeclined an interview request until the confirmation process is completed, butshe pledged renewed cooperation with NASA during a Senate hearing last month.

"Ibelieve that both NOAA and NASA intend to have the best possiblerelationship," Lubchenco said.

NASA alreadyhandles acquisition and some management duties for NOAA weather satellites. Anew DSCOVR mission would also require a strong partnership between the agencies.

PresidentObama's fiscal year 2010 budget outline proposed $1.3 billion for NOAAsatellite programs, an increase over fiscal year 2009 levels, but more detailswon't be revealed until April.

If DSCOVR ischosen for implementation, the ultimate science payload would have to bebalanced with funding concerns, especially the cost of a launch vehicle,according to Davis.

Managersoriginally wanted to use an Air Force Minotaur 5 rocket to launch thesatellite, but engineers found the spacecraft would not fit on that booster.

Depending onits final mass, the spacecraft would likely fly on a Delta 2 or Falcon 9rocket. Davis stressed those are very preliminary discussions and any finaldecision is months or years away.

A NASA studyfrom 2007 concluded that DSCOVR could be refurbished, tested and launchedaboard a Delta 2 rocket for about $205 million. But that estimate was based onan Earth observation mission using instruments already built.

Launch wouldprobably occur in about 2013, officials said.

But NOAAofficials must first finish examining NASA's report and decide whether topursue the mission.

"If thenumbers seem to make sense to us, and the powers-that-be think it's worthwhile,we could potentially ask for funding to do this," Davis said.

If themission is approved, NASA would prepare the satellite for launch, the Air Forcewould help fund the launch, and NOAA would operate the spacecraft.

Engineerswant to put the craft through a new round of environmental tests to check thesatellite's response to the intense sounds, vibrations and temperature swingsit would experience during flight.

Somecomponents may have to recertified or replaced, including DSCOVR's reactionwheels, star tracker and flight battery.

"Theseare preliminary assessments and NOAA and NASA will develop a more definite planif the decision is made to proceed," a NOAA spokesperson said.

NOAA beganconsidering using DSCOVR for solar wind studies in 2007.

SpaceServices Inc., a Houston-based company that specializes in launching crematedremains into space, approached the government with a proposal to redevelop thespacecraft for solar observations. Space Services would have sold the data tothe government.

Governmentand commercial organizations were unable to reach an agreement.

NASA finallyacted on NOAA's suggestion last year after Congress passed the NASAAuthorization Act of 2008.

The billrequired NASA to submit its plans for DSCOVR to Congress 180 days after thelegislation became law. That deadline is in April.

Steve Cole,a NASA spokesperson, said the congressional report is separate from the NOAAsolar wind study, but the work could fulfill the obligation if NOAA chooses togo ahead with the mission.

The Obamaadministration's transition team also asked NASA officials about the status ofthe DSCOVR mission.

"NASAcame back to us and asked us if we still had interest," Davis said."We got to the point where NOAA and the Air Force could pay NASA to dothis study."

Missionlong stalled

DSCOVR wasoriginally approved in October 1998 as a mission to continuously observe thesunlit side of Earth from the L1 point.

The idea wasfirst proposed by former Vice President Al Gore during a speech at theMassachusetts Institute of Technology in March 1998. Gore's vision was for themission to produce live imagery of the full sunlit disk of Earth 24 hours aday. The pictures were to be posted on the Internet.

Gore namedthe project Triana,after the sailor that first spotted land on Columbus's 1492 voyage to theAmericas.

"Thisnew satellite...will allow people around the globe to gaze at our planet as ittravels in its orbit around the sun for the first time in history," Goresaid in the announcement.

NASA addedseveral instruments to Triana in an attempt to build scientific support for themission, but the additions drove up the satellite's cost.

The higherprice tag caught the attention of the agency's own inspector general. Theinternal watchdog issued a report in 1999, criticizing Triana's rising cost andexpressing concern over the mission's scientific merit.

Triana wasoriginally due to launch on a space shuttle mission in 2000, but Congressordered NASA to put the project on hold in late 1999 pending a review by theNational Research Council.

CongressionalRepublicans called the satellite an overpriced "screen saver" andcriticized the mission as one of Gore's pet projects.

The council,part of the National Academy of Sciences, concluded in March 2000 that Trianawas a worthwhile mission that would collect unique data with importantapplications in climate change research.

The group"found that the Triana mission will complement and enhance data from othermissions because of the measurements obtainable at the L1 point in space,"according to the report.

Triana'ssensors would have measured ozone and cloud distributions, vegetation changes,atmospheric pollution, and the planet's radiation budget. The PlasMaginstrument package was also included to study the solar wind.

Theindependent review team also noted NASA's contention that the project's primaryfocus was on technology demonstration instead of science.

"However,as an exploratory mission, Triana's focus is the development of new observingtechniques, rather than a specific scientific investigation," the reportsaid.

NASAexplicitly described Triana's objectives as exploratory. Officials said thespacecraft would have demonstrated the potential for using L1, home to severalsolar observatories, as a location for Earth science.

Valeroacknowledges the satellite's "innovative" observation method, but hecontends DSCOVR's mission was rooted in science geared toward climate changeresearch.

DSCOVR'sEarth-pointing telescope and radiometers, still bolted to the spacecraft today,are designed to check the planet's thermostat by gauging solar radiationreaching the planet.

Theradiation balance would tell scientists whether Earth is warming or coolingbased on the difference in energy that is absorbed and released each year,Valero said.

Scientistsalready know the planet has a radiation imbalance a few times greater than thegreenhouse effect of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Valero saida deep space Earth observatory would give scientists a new way of studying theplanet by facilitating continuous imagery. Other Earth observation satellitesfly in low-altitude orbits and collect global data on a timescale of days.

"I amnot watching, say, San Francisco, then 10 hours later, New York, and thenDenver," Valero said. "I'm looking at the whole thing now."

The newparadigm demonstrated by DSCOVR would be more reliable because using low Earthorbit satellites is like "looking at the forest tree by tree," Valerosaid.

NASA decidedto suspend work on Triana in 2001, months after former President Bush tookoffice following his defeat of Gore in the 2000 election.

"Parts,ground support equipment and documentation were impounded and saved," Colesaid.

Thespacecraft was transferred to a clean room at Goddard in November 2001, whereit was stored under nitrogen purge conditions until it was removed for testinglast November.

Cole saidearlier reports pegging the cost of DSCOVR's storage in a space age warehouseat $1 million per year were inaccurate. The real cost was closer to severalthousand dollars per year, according to Cole.

Triana wasrenamed DSCOVR before NASA quietly cancelled the mission in 2005, citing thedwindling number of remaining shuttle flights and a lack of funding torefurbish and launch the satellite.

Thecancellation came after NASA had spent $97 million on the project, Cole said.

France andUkraine later proposed launching DSCOVR on Ariane and Tsyklon rockets, but NASAdid not accept the offer, according to Valero.

TheUkrainian plan even included a free launch, Valero said.

But federallaw restricts NASA payloads launching on foreign rockets.

NASA nowrelies on the science community for advice for new projects.

Aftercriticism regarding the way NASA selects space and Earth science missions,officials began soliciting regular input from independent scientists.

"It'simportant to know that NASA is now using input from the broad Earth sciencecommunity in deciding which missions to pursue in the future," Cole said.

Therecommendations come from a decadal survey prepared by a committee of theNational Research Council, the same group that reviewed the Triana mission in2000.

Thecommittee's first decadal survey was submitted in January 2007 to advise NASAon the science community's highest priorities in Earth science.

Cole saidthe team reviewed a number of proposed missions, but DSCOVR was not among the17 projects recommended for execution by NASA and NOAA.

NASA alsocommissioned an ad-hoc science workshop in May 2007 to evaluate DSCOVR'scontributions to climate science.

That groupconcluded that the mission would provide useful data, but "DSCOVRmeasurements would not fulfill the climate science requirements established inthe NRC decadal survey," Cole said.

Thatscientific verdict led NASA to begin considering other options for DSCOVR. TheNASA Authorization Act of 2008 passed last year forced the issue.

The nextchapter of DSCOVR's story remains unwritten, and the spacecraft still facesmore obstacles before being shot into space, but the long-forgotten satellitehas not been this close to launch in more than seven years.

NASAreassembled much of DSCOVR's old team for the tests. Many engineers were notsure if they would ever work on the project again.

The workersare now waiting to hear if they will be called on to bring DSCOVR back to lifeagain, this time for good.

"We sitand wait," Burt said. "There's no next step until we get amandate."

- New Video - NASA's Orbiting Carbon Observatory to Track Climate Change

- Video - Goldilocks, Science and Climate Change

- Video - Antarctic Ice Shelf Disintegrates

Copyright 2009 SpaceflightNow.com,all rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Stephen Clark is the Editor of Spaceflight Now, a web-based publication dedicated to covering rocket launches, human spaceflight and exploration. He joined the Spaceflight Now team in 2009 and previously wrote as a senior reporter with the Daily Texan. You can follow Stephen's latest project at SpaceflightNow.com and on Twitter.