A new study that claims to present evidence of alien life is being met with a healthy dose of skepticism in the scientific community.

On July 31, a team of British researchers sent a balloon into the stratosphere over England, where it collected samples at an altitude range of 14 miles to 17 miles (22 to 27 kilometers). The balloon's scientific payload returned to Earth toting the cell wall, or frustule, of a type of microscopic algae called a diatom, the scientists report in the Journal of Cosmology.

While bacteria and other tiny lifeforms have been found high above the planet before — storm clouds are teeming with microbes, for example — the new discovery is potentially of monumental importance, study team members say. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life ]

"Most people will assume that these biological particles must have just drifted up to the stratosphere from Earth, but it is generally accepted that a particle of the size found cannot be lifted from Earth to heights of, for example, 27 km. The only known exception is by a violent volcanic eruption, none of which occurred within three years of the sampling trip," lead author Milton Wainwright, of the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom, said in a statement Thursday (Sept. 19).

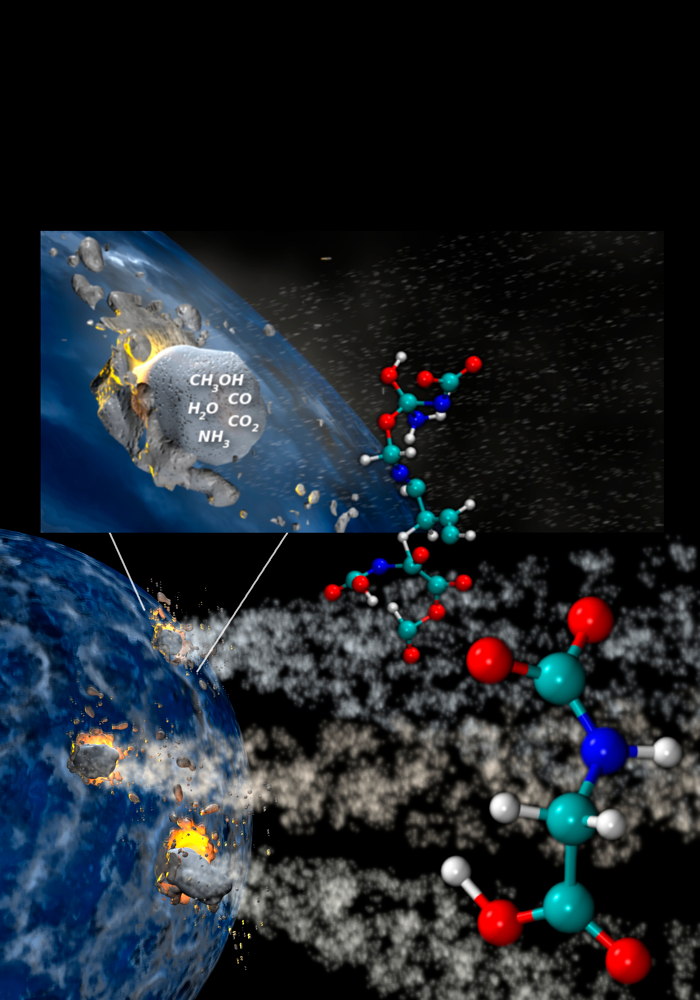

"In the absence of a mechanism by which large particles like these can be transported to the stratosphere, we can only conclude that the biological entities originated from space," Wainwright added. "Our conclusion then is that life is continually arriving to Earth from space, life is not restricted to this planet and it almost certainly did not originate here."

The diatom fragment may have been delivered to Earth by a comet, Wainwright and his colleagues write in the paper, which can be read here at the Journal of Cosmology.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The idea that life is widespread throughout the universe and has been transported to many worlds by objects such as comets — a notion known as panspermia — is credible, at least over relatively short cosmic distances, said astronomer Seth Shostak of the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, Calif.

However, that doesn't necessarily mean the new study will stand up to the intense scientific scrutiny it's likely to receive, he said.

"In the past, most members of the astrobiology community have found it easier to ascribe these claims to terrestrial contamination than to extraterrestrial hitchhikers," Shostak told SPACE.com via email. "It remains to be seen whether that opinion will be changed by these new results." [10 Alien Encounters Debunked]

Indeed, other scientists said they would like to see more convincing evidence of a cosmic origin for the organism snagged by the balloon.

"There is probably truth to the report that they find curious stuff in the atmosphere," Chris McKay, an astrobiologist at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., told SPACE.com via email. "The jump to the conclusion that it is alien life is a big jump and would require quite extraordinary proof. (The usual Sagan saying: extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.)"

McKay gave an example of what might constitute such extraordinary evidence.

"If they were able to show that it was composed of all D amino acids (proteins in Earth life are made of L amino acids), that would be pretty convincing to me," he said. "So some sort of biochemical indication that it does not share Earth biochemistry. If it does indeed share Earth biochemistry, proving that it is of alien origin is probably impossible."

Further study needed

Wainwright and his team plan to study their stratospheric samples further in an attempt to find a smoking gun for an off-Earth origin. For example, the researchers will analyze the ratios of various isotopes, which are varieties of an element that have different numbers of neutrons in their atomic nuclei.

"If the ratio of certain isotopes gives one number, then our organisms are from Earth; if it gives another, then they are from space," Wainwright said.

However, astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch of Washington State University thinks the study team should have performed such follow-up analyses, and consulted diatom experts, before publishing its provocative claim.

"Perhaps the fragment came actually from the stratosphere and is not contamination, but basing this conclusion only on one particle and very limited analysis seems quite odd to me and inferring an extraterrestrial origin completely off-base," Schulze-Makuch told SPACE.com via email.

Schulze-Makuch also thinks comets are unlikely incubators for life, suspecting that life first arose on a planetary body. And the presence of a diatom on a comet would be especially surprising, he said.

"Diatoms are actually relatively advanced life forms on Earth and developed most likely sometime at the beginning of the Mesozoic (probably Jurassic time period), thus very late during evolution (probably at least 3 billion years after the origin of life on Earth)," Schulze-Makuch said, adding that diatoms are typically aquatic and there is no liquid water on a comet, except during the brief periods when the icy objects approach the sun.

"Besides, I would expect an extraterrestrial organism or even remnant of an organism to be quite different from what we see on Earth in some significant ways (as the environment around it, its 'habitat,' will affect the form and function of the organism), and certainly not be linked to some kind of diatom species on Earth," Schulze-Makuch said.

Other controversial claims

The Journal of Cosmology is no stranger to bold claims. Two years ago, for instance, it published a controversial study that purported to have found evidence of fossilized life in meteorites.

That paper was not well received by outside scientists, some of whom questioned the journal's credibility as well.

"It isn't a real science journal at all, but is the ginned-up website of a small group of crank academics obsessed with the idea of [Fred] Hoyle and [Chandra] Wickramasinghe that life originated in outer space and simply rained down on Earth," P.Z. Myers, a biologist at the University of Minnesota, Morris, wrote on his popular science blog Pharyngula at the time.

Wickramasinghe is a co-author of the new stratospheric diatom paper, a fact that could color its reception in the wider scientific community.

"I don't have ANY expertise in this area," Rosie Redfield, a microbiologist at the University of British Columbia, told SPACE.com via email. Redfield was among the outspoken critics of the Journal of Cosmology's 2011 meteorite announcement. "But neither the Journal of Cosmology nor Dr. Wickramasinghe have any scientific credibility, and one fragment of a diatom frustule is hardly significant evidence."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.