Strange Spinning Star Is 'Missing Link' of Pulsars

A perplexing fast-spinning star just might be the "missing link" in a long-standing pulsar mystery, scientists say.

The so-called neutron star — a city-sized stellar remnant born from the explosive death of a larger star — is located about 18,000 light-years from Earth has the never-before-observed ability to change from one kind of pulsar to another and back again. You can watch a video animation of the pulsar here set to the music of rock band Atom Strange.

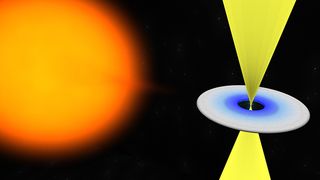

Pulsars are rapidly spinning neutron stars that come in different varieties, but scientists could not pin down the relationship between two kinds of pulsars until now.

"For the first time we see both X-rays and extremely fast radio pulses from the one pulsar," said Simon Johnston, head of astrophysics at the Sydney, Australia-based Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) astronomy and space science division, in a statement. "This is the first direct evidence of a pulsar changing from one kind of object into another — like a caterpillar turning into a butterfly." [The Top 10 Star Mysteries of All Time]

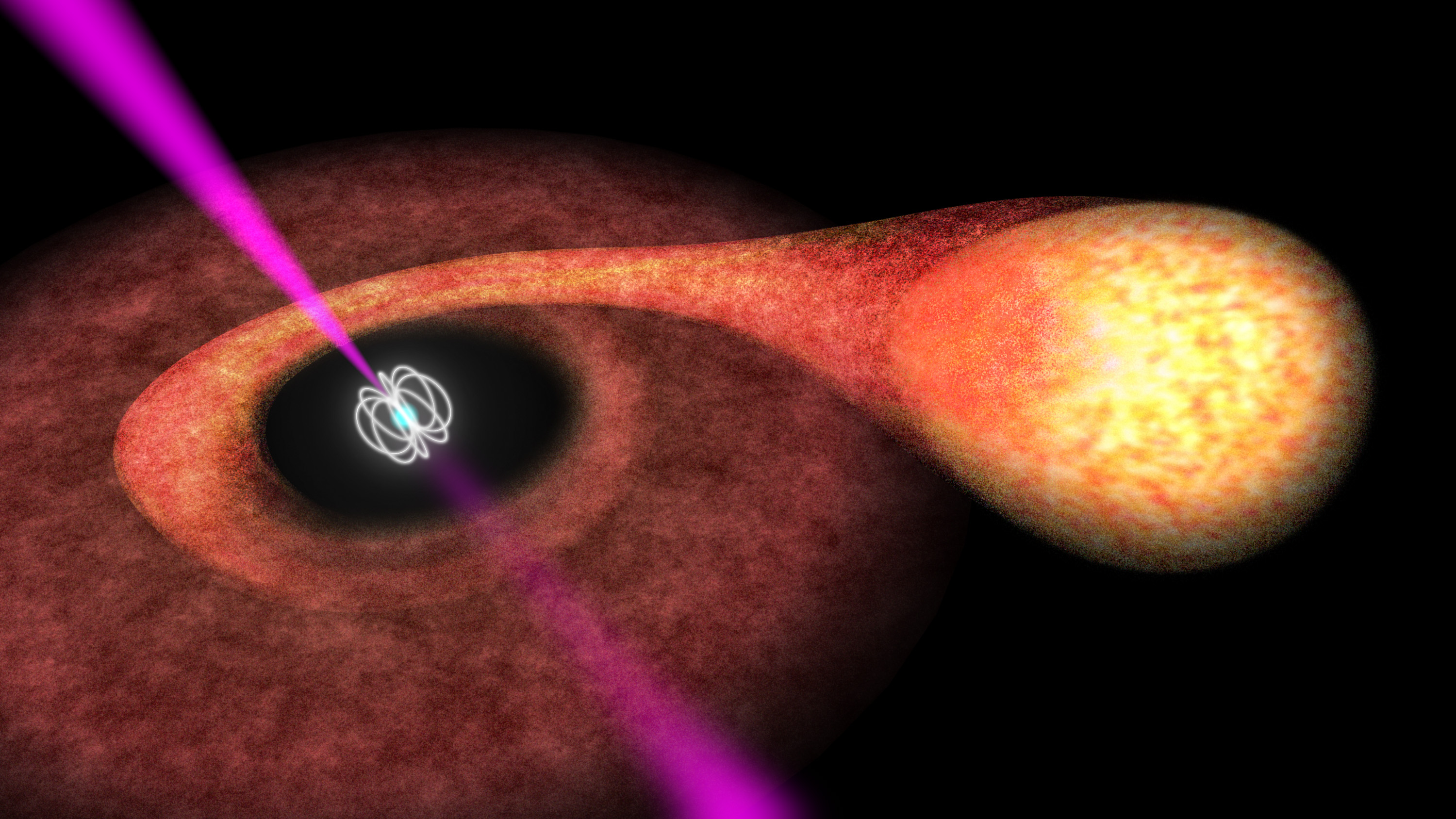

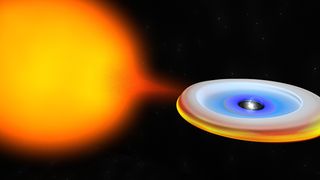

The pulsar (named PSR J1824-2452I) spews out x-rays or radio pulses depending on how much matter its companion star is shooting in its direction at any given time, scientists have found.

The companion star — that only has about one-fifth the mass of the sun — sometimes pounds the pulsar with speeding streams of matter. Scientists found that the pulsar's magnetic field can protect the star from the onslaught of stellar material, but sometimes it becomes overwhelmed by the intensity of the steams.

When the magnetic field can no longer stop the matter from reaching the surface of the pulsar, the spinning star shoots out jets of x-rays. Eventually, the pulsar's magnetic field starts protecting the star again after the companion star has settled down.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We've been fortunate enough to see all stages of this process, with a range of ground and space telescopes," Alessandro Papitto, astronomer and lead author of a study detailing the new findings in the journal Nature this week, said in a statement. "We've been looking for such evidence for more than a decade."

Originally, scientists thought that pulsars in binary systems slowly accreted material shot out by their companion stars, causing the pulsar to gradually "spin up" into what is known as a millisecond pulsar: a neutron star that emits radio waves while spinning at hundreds of times a second.

However, this new finding shows that it might be a process that goes in fits and starts depending on when the built-up matter in the accretion disk falls into the pulsar.

"It’s like a teenager who switches between acting like a child and acting like an adult," John Sarkissian, who observed the system with CSIRO's Parkes radio telescope in eastern Australia, said in a statement. "Interestingly, the pulsar swings back and forth between its two states in just a matter of weeks."

Learn more about the band Atom Strange featured in the new pulsar video here: www.atomstrange.com

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.