Future Mars explorers may be able to get all the water they need out of the red dirt beneath their boots, a new study suggests.

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has found that surface soil on the Red Planet contains about 2 percent water by weight. That means astronaut pioneers could extract roughly 2 pints (1 liter) of water out of every cubic foot (0.03 cubic meters) of Martian dirt they dig up, said study lead author Laurie Leshin, of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y.

"For me, that was a big 'wow' moment," Leshin told SPACE.com. "I was really happy when we saw that there's easily accessible water here in the dirt beneath your feet. And it's probably true anywhere you go on Mars." [The Search for Water on Mars (Photos)]

The new study is one of five papers published in the journal Science today (Sept. 26) that report what researchers have learned about Martian surface materials from the work Curiosity did during its first 100 days on the Red Planet.

Soaking up atmospheric water

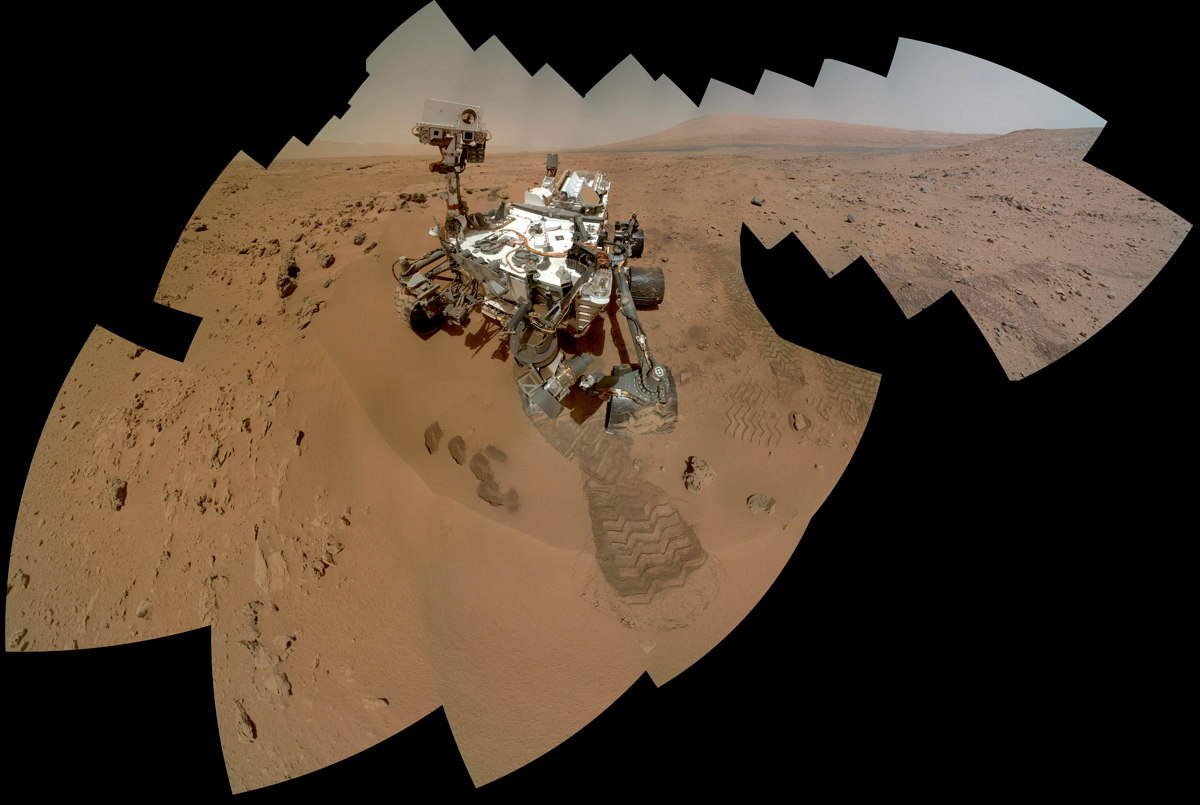

Curiosity touched down inside Mars' huge Gale Crater in August 2012, kicking off a planned two-year surface mission to determine if the Red Planet could ever have supported microbial life. It achieved that goal in March, when it found that a spot near its landing site called Yellowknife Bay was indeed habitable billions of years ago.

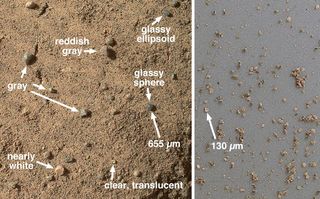

But Curiosity did quite a bit of science work before getting to Yellowknife Bay. Leshin and her colleagues looked at the results of Curiosity's first extensive Mars soil analyses, which the 1-ton rover performed on dirt that it scooped up at a sandy site called Rocknest in November 2012.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Using its Sample Analysis at Mars instrument, or SAM, Curiosity heated this dirt to a temperature of 1,535 degrees Fahrenheit (835 degrees Celsius), and then identified the gases that boiled off. SAM saw significant amounts of carbon dioxide, oxygen and sulfur compounds — and lots of water on Mars.

SAM also determined that the soil water is rich in deuterium, a "heavy" isotope of hydrogen that contains one neutron and one proton (as opposed to "normal" hydrogen atoms, which have no neutrons). The water in Mars' thin air sports a similar deuterium ratio, Leshin said.

"That tells us that the dirt is acting like a bit of a sponge and absorbing water from the atmosphere," she said.

Some bad news for manned exploration

SAM detected some organic compounds in the Rocknest sample as well — carbon-containing chemicals that are the building blocks of life here on Earth. But as mission scientists reported late last year, these are simple, chlorinated organics that likely have nothing to do with Martian life. [The Hunt for Martian Life: A Photo Timeline]

Instead, Leshin said, they were probably produced when organics that hitched a ride from Earth reacted with chlorine atoms released by a toxic chemical in the sample called perchlorate.

Perchlorate is known to exist in Martian dirt; NASA's Phoenix lander spotted it near the planet's north pole in 2008. Curiosity has now found evidence of it near the equator, suggesting that the chemical is common across the planet. (Indeed, observations by a variety of robotic Mars explorers indicate that Red Planet dirt is likely similar from place to place, distributed in a global layer across the surface, Leshin said.)

The presence of perchlorate is a challenge that architects of future manned Mars missions will have to overcome, Leshin said.

"Perchlorate is not good for people. We have to figure out, if humans are going to come into contact with the soil, how to deal with that," she said.

"That's the reason we send robotic explorers before we send humans — to try to really understand both the opportunities and the good stuff, and the challenges we need to work through," Leshin added.

A wealth of discoveries

The four other papers published in Science today report exciting results as well.

For example, Curiosity's laser-firing ChemCam instrument found a strong hydrogen signal in fine-grained Martian soils along the rover's route, reinforcing the SAM data and further suggesting that water is common in dirt across the planet (since such fine soils are globally distributed).

Another study reveals more intriguing details about a rock Curiosity studied in October 2012. This stone — which scientists dubbed "Jake Matijevic" in honor of a mission team member who died two weeks after the rover touched down — is a type of volcanic rock never before seen on Mars.

However, rocks similar to Jake Matijevic are commonly observed here on Earth, especially on oceanic islands and in rifts where the planet's crust is thinning out.

"Of all the Martian rocks, this one is the most Earth-like. It's kind of amazing," said Curiosity lead scientist John Grotzinger, a geologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. "What it indicates is that the planet is more evolved than we thought it was, more differentiated."

The five new studies showcase the diversity and scientific value of Gale Crater, Grotzinger said. They also highlight how well Curiosity's 10 science instruments have worked together, returning huge amounts of data that will keep the mission team busy for years to come.

"The amount of information that comes out of this rover just blows me away, all the time," Grotzinger told SPACE.com. "We're getting better at using Curiosity, and she just keeps telling us more and more. One year into the mission, we still feel like we're drinking from a fire hose."

The road to Mount Sharp

The pace of discovery could pick up even more. This past July, Curiosity left the Yellowknife Bay area and headed for Mount Sharp, which rises 3.4 miles (5.5 kilometers) into the Martian sky from Gale Crater's center.

Mount Sharp has been Curiosity's main destination since before the rover's November 2011 launch. Mission scientists want the rover to climb up through the mountain's foothills, reading the terrain's many layers along the way.

"As we go through the rock layers, we're basically looking at the history of ancient environments and how they may be changing," Grotzinger said. "So what we'll really be able to do for the first time is get a relative chronology of some substantial part of Martian history, which should be pretty cool."

Curiosity has covered about 20 percent of the planned 5.3-mile (8.5 km) trek to Mount Sharp. The rover, which is doing science work as it goes, may reach the base of the mountain around the middle of next year, Grotzinger said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.