Here is a trivia question: Not including our own planet Earth, how many planets are visible without using any optical aid, be it binoculars or a telescope? Most people will usually answer five: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

But in actuality, the correct answer is six.

The sixth planet which can be spied without optical aid is the planet Uranus. This week will be a fine time to try and seek it out, especially since it favorably placed for viewing in our evening sky now that the bright Moon has finally moved out of the way. In addition, on Oct. 3 Uranus will be at opposition to the sun all will be visible in the sky all night. [Photos of Uranus, the Odd Tilted Planet]

Of course, you'll have to know exactly where to look for it.

Barely visible by a keen naked eye on very dark, clear nights, Uranus is now visible during the evening hours among the stars of Pisces, the Fishes. Astronomers measure the brightness of objects in the night sky as magnitude. Smaller numbers indicate brighter objects, with negative numbers denoting exceptionally bright objects. But Uranus is currently shining at magnitude +5.7, relatively dim on the scale.

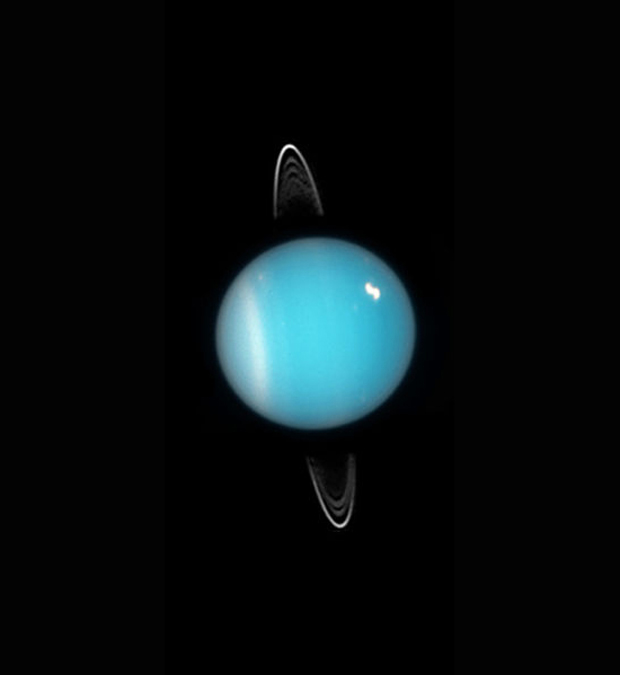

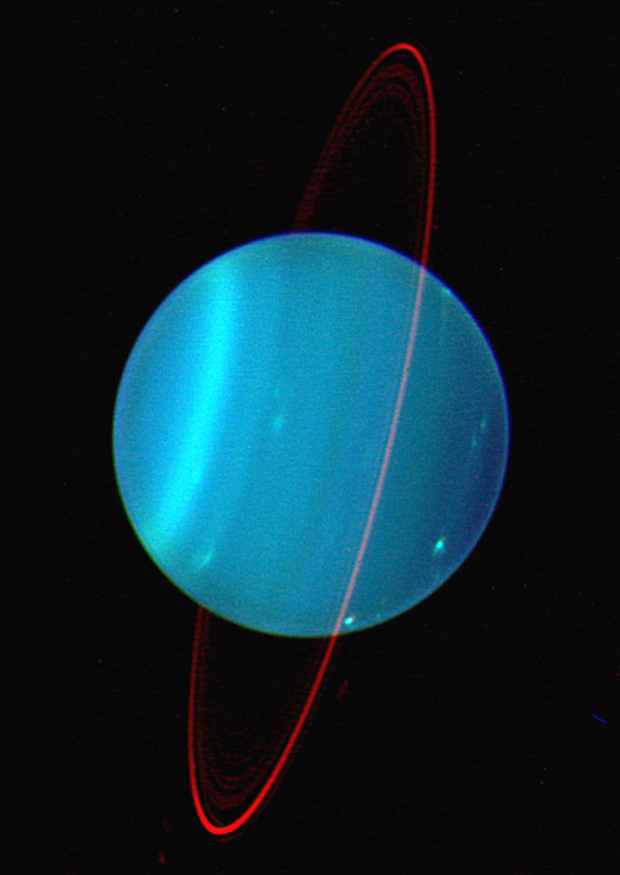

When hunting Uranus, it is best to carefully study a star map of that part of the sky where the planet is located, and then scan that region with binoculars. A small telescope with at least a 3-inch aperture and magnification of 150-power, you should be able to resolve it into a tiny, pale-green featureless disk.

Bizarre circumstances for Uranus

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This week, Uranus is 1.77 billion miles (2.85 billion kilometers) from Earth and 1.86 billion miles (3 billion km) from the sun.

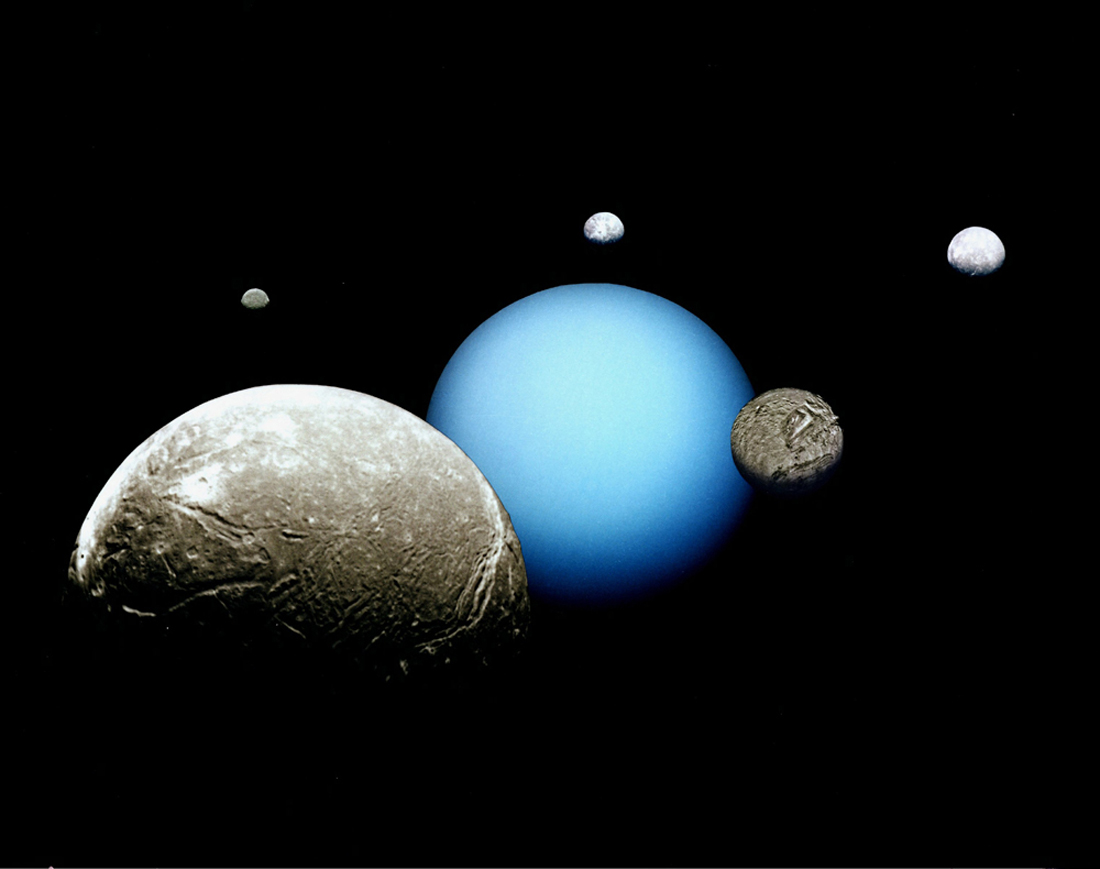

The planet is 31,800 miles (51,200 km) in diameter and according to flyby magnetic data from Voyager 2 in 1986, has a rotation period of 17.4 hours. At last count, Uranus has 27 moons, all in orbits lying in the planet’s equator in which there is also a complex of nine narrow, nearly opaque rings, which were discovered in 1978. [How Well Do You Know Uranus? Take Our Quiz!]

Uranus likely has a rocky core, surrounded by a liquid mantle of water, methane, and ammonia, encased in an atmosphere of hydrogen and helium. A very strange feature is how far over Uranus is tilted; its axis of rotation is tilted sideways, nearly into the plane of its revolution about the sun. Its north and south poles therefore lie where the other planets have their equators.

Its north pole lies 98 degrees from being directly up and down to its orbit plane. Thus, its seasons are extreme: when the Sun rises at its north pole, it stays up for 42 Earth years; then it sets and the north pole is in darkness for 42 Earth years.

Saga of discovery

The British astronomer Sir William Herschel discovered Uranus on March 13, 1781, noting that it was moving slowly through the constellation Gemini. Uranus was actually observed on many occasions prior to its discovery by Herschel.

The earliest known observation was made in 1690 by John Flamsteed an English astronomer and the first Astronomer Royal. He catalogued over 3000 stars, one of which later turned out to be Uranus. He had unknowingly made at least half a dozen other observations of the planet, yet on each occasion he mistakenly recorded it as nothing more than a faint star.

When Herschel first caught sight of Uranus, he had thought he had discovered a new comet. Soon the name of Herschel became known over all of Europe together with the news of his discovery. King George III, who loved the sciences, had the astronomer presented to him and provided him with a life pension and a residence at Slough, in the neighborhood of Windsor Castle.

Eventually it was determined that Herschel's "comet" was in fact, a new planet. For a while, it actually bore Herschel's name. But Herschel himself proposed the name Georgium Sidus, "The Star of George," after his benefactor.

However, Herschel's proposed name was not popular outside of Britain, and alternatives were soon proposed. The custom for a mythological name ultimately prevailed and the new planet was finally named Uranus.

Uranus is the only planet whose name is derived from a figure from Greek mythology rather than Roman mythology like the other planets, from the Latinized version of the Greek god of the sky, Ouranos. Prior to its discovery, the outermost planet was considered to be Saturn, named for the ancient god of time and destiny, but Uranus was the father of Saturn and considered the most ancient deity of all.

I think in retrospect that this was probably for all for the best. After all, if Herschel's request had been granted, just think of how we might have eventually listed the planets in order from the sun: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and … George?

Editor's note: If you snap a great telescope photo of Uranus, pr any other night sky view, and you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y.Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.