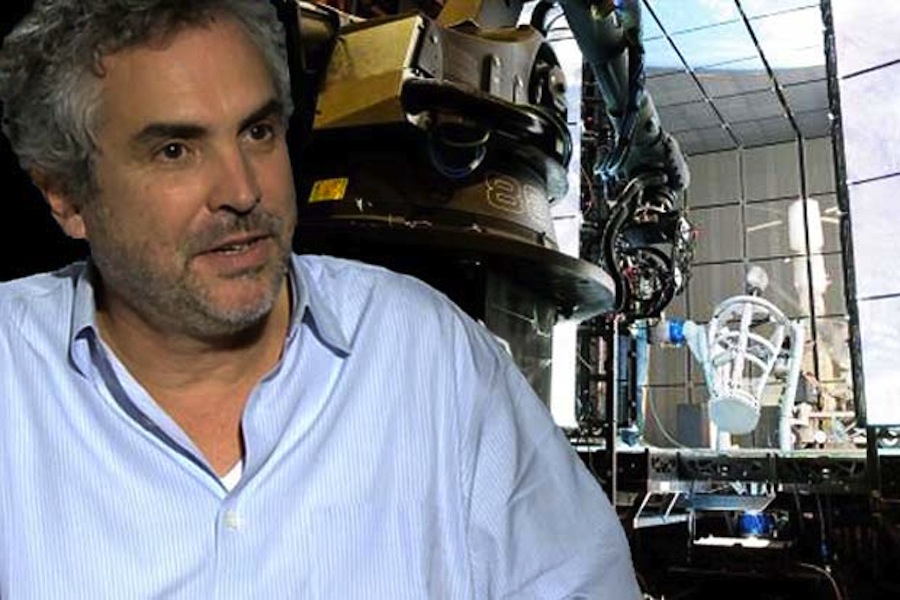

Making 'Gravity': How Filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón Created 'Weightlessness' Without Spaceflight

"Gravity" is a weighty movie. Alfonso Cuarón has been shouldering its crushing mass for nearly five years. Cuarón, who directed the film, based on a story by his son Jonas and a script they co-wrote, says he is done with space. But not before inventing a new way to light, shoot and direct, which will likely impact the way cinema will be made from now on.

"Gravity" is the story of a gifted medical researcher, self-alienated from Earth and the community of humans, who must confront her deepest demons, ultimately deciding the cost-benefit ratio of survival. The movie puts lead actor Sandra Bullock all alone in space — and on screen — for enormous stretches of time.

For the Cuaróns, space offered a rich field of metaphor. In weightlessness, the inertia of one's personality — gravitas — can become an almost physical force. There are cocoons of survival (spacesuits, ships, and stations) challenging the stark deadliness of the universe for an unprotected human. [See thrilling photos from the space film "Gravity"]

One can take little bits and pieces of Earth's environment into space. But the Mother Planet's immense gravity will always try to bring you home. That's when physics makes her life-giving atmosphere a potentially deadly barrier to cross, and a toll must be paid.

To bring this heavy story down to Earth and into audience's hearts meant making 90 minutes of flawlessly believable microgravity illusion on detailed sets depicting spacecraft that are well known worldwide. Cuarón calls this film his "love song to space." To be a faithful lover required that he celebrate the true space experience, portraying every aspect with as much realism as cinema technology could muster.

“Gravity” successfully recreates lack of gravity

Without a gravity vector, physical forces come out to play, with Sir Isaac Newton calling the tune. Set an object rotating in microgravity and it will not slow visibly until some other force acts upon it.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Watching the film, it's quite clear that astronauts — who have been there and done that — advised the filmmakers. The behavior of masses handled by intelligent gloved hands on an EVA is hard to fake. When that mass is a space-suited astronaut, "torqued" around by the movement of a much more massive spacecraft, only someone who has experienced it can describe the feeling. ["Gravity's" Astronaut Advisors: Fears and Family in Space (Video)]

What happens when a tethered astronaut is accelerated — or two spacewalkers, tethered together, jerk one another around — has emotional consequences that can only be felt by an audience if the filmmakers get the physics absolutely right.

Pre-visualization rules

The requirement of realism, paradoxically, compelled Cuarón and his team to pre-visualize the entire film, shot for shot, long in advance of bringing Sandra Bullock and co-star George Clooney onset. This was an animation technique. Each shot was blocked, timed, and the actors "key-framed," creating an "animatic" of the entire script.

Animators had to unlearn years of expectations. Everybody "knows" that objects fly on curved trajectories to the ground based on their weight. But in orbit, weight translates to inertia, there is no ground, and there is only the tiniest hint of gravitational force to change the path. [Making Gravity: How Alfonso Cuarón Created 'Weightlessness' (Video)]

"It took a lot of education for the animators to fully grasp that the usual laws of cause and effect don’t apply," Cuarón said in a press statement. "In outer space, there is no up; there is no down."

It took more than two years of this "previs" process before the director's first "Action!" call.

When cameras finally did roll, Bullock and Clooney found themselves under some tight space and time constraints. There wasn't much room for improv. Each shot's pacing was closely defined by the "previs," which tended to tie the actors tightly to time. This effectively took many possibilities for spontaneous moments off the table.

Visual effects supervisor Tim Webber ("The Dark Knight") worked diligently to retain options for the live shoot. But in most cases Cuarón would make the call to commit, locking the live-action yet to be shot months in advance.

Cuarón credits Bullock and Clooney with finding myriad ways to convey deep emotions under unyielding technical limitations. "Watching their performances, no one will feel the limitations placed on them, and that is a testament to what amazing actors they are," he said.

How to light a space movie

Early in the "previs" process, Director of Photography Emmanuel Lubezki ("Children of Men") recognized a looming problem: In space, light comes from the sun and bounces off everything else, most prominently the dayside of Earth. But the script called for rapidly changing lighting as primal forces whip characters around. How could the film crew, essentially, move the sun around instantly?

Lubezki's answer was to invent something new under the sun: A "Light Box," made of 196 panels, each containing 4096 LEDs. Actors and set pieces could be placed inside. Panels could move to accommodate cameras and props. Visual effects technicians piloting software could instantaneous change any individual LED.

The whole rig was more than 20 feet (6 meters) tall and over 10 feet (3 m) wide.

Imagine yourself as Sandra Bullock or George Clooney, hanging on an intricate 12-wire rig, inside a small house made of flat-screen TV's. Not only can the Light Box make instant and interactive changes of light falling your face, your costume, your props; it also can show you the scene to which you are supposed to be reacting.

Specific areas of the Earth, parts of the International Space Station, your co-stars' spacesuit helmet lights in proper perspective; any object making, reflecting or refracting light – or the absence of light – can be painted on the Light Box. And that light drives the story as the orbits cycles in and out of metaphorical darkness.

Bullock used the loneliness of the Light Box as motivation for bringing the character forth. "There was no human connection, other than the voices coming through my little earwig, which helped because it made me feel so alone," she wrote in a statement.

We have all seen how the robot arms on NASA's space shuttles and the International Space Station work. Ironically, a computer-controlled camera on a highly specialized robot was the only "living" thing sharing the Light Box with Bullock for much of the shoot.

In tight coordination with the light changes mad possible by the Box, the robot camera made for precise moves, ranging from delicate and subtle to bombastic and radical, with the complete repeatability needed to nail the perfect take.

The Light Box/robot camera combination is almost certain to be a game-changer in movie making hereafter.

Tracking shots: You are there

With the lighting problem solved, the free realm of virtual microgravity made it possible – but very challenging technically — for Cuarón to play one of his favorite cards: Long, complex, tracking shots.

Cuarón’s prior films "Children of Men" and "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban," as examples, contain elaborate continuous sequences, traveling over large distances without a cut. These transform audiences from observers to participants in the scenes, living in the tempos of these movies.

But in "Gravity's" universe, the distances can be much larger; the timeframes much longer, and the camera angles can pivot fully through three dimensions.

This let DP Lubezki expand Cuarón’s love of long uninterrupted takes into what they began calling “elastic shots;” extended floating sequences where the camera, actor and scene could rotate and roll around one another in apparently complete dimensional freedom. This instantly communicates the feeling of true space operations.

When your guts aren't being knocked about in resonance with the emotional slalom run of Sandra Bullock's character, you're getting woozy (in an exhilarating way) with the view through Cuarón's loopy moving camera. He'll take you around, over/under, through, and in and out of micro-spaces within the ultimate macro: space itself.

One moment you're inside the spacesuit helmet Bullock's character, her breath whispering in your ears. The next, you're a kilometer out from the International Space Station hearing her only as distant radio chatter, then you're up close with co-star George Clooney's character — and there hasn’t been a cinematic cut.

Suspending disbelief

Getting these shots required precise choreography, over several years, between pre-vis, live action and laborious tasks of final animation.

Cuarón insisted that this film create a photorealistic world of high fidelity space artifacts, objects and astronauts. "Gravity" is not a fantasy, nor a cartoon, nor is it even close to much classic science fiction. It is a metaphor-driven dramatic story of a flesh and blood and soul human being.

Most of us have seen images from space for most of our lives. VFX Supervisor Webber had to stay totally faithful to that body of imagery. "Astronauts actually make very good photographers," he writes. "We would look at the time lapse shots they did from the ISS and say 'Gosh, if we did something like that, no one would believe it was real.'"

The film’s art director painstakingly recreated the look of spacecraft and tools, which many of us have seen and could quickly judge as phony if not near perfect. Then they added a layer of distress, wear and tear to reference the continuous occupation of the International Space Stationand other craft.

They also took some liberties needed to drive the story. Purists will note some "mods" to the Soyuz, for example.

Much of this work was done with computer modeling of surfaces, including spacesuits. There is no moment when you, the viewer, can discern what was actually present on the set and what was generated in final rendering.

There IS sound in space

Sound, of course, doesn't travel through vacuum. But it absolutely conducts through structures and spacesuits.

Touch a tool or an active spacecraft and you hear and feel its acoustic signature; let it go and it sounds entirely inert. A lot of "Gravity's" sound design is carefully planned to convey this alien experience.

Cuarón and the sound team also surprises us with silence, when needed to tell the tale. And in some cases, sonic structures that are part musical and part effects suggest the moods of spaces.

Final cut

Though there are some exquisitely delicate moments, this film isn't subtle. Some of the havoc Alfie wreaks on elegant and expensive space structures will make strong engineers whimper in professional pain.

Cuarón is also not above giving us a horror film-style human-remains gut-punch or two. You may be shocked but you won’t feel disgusted; and you won't ever feel cheap.

The complex tech needed to bring "Gravity" to life never overshadows Cuarón's metaphorical purpose. Space is the perfect place to lay the human soil bare.

"I thought the film would be a lot simpler," says Cuarón, "It was not until we started trying conventional techniques that I realized … we were going to have to create something entirely new …We wanted it to look like we took our camera into space."

That isn't (yet) possible. But the techniques pioneered on Cuarón’s "Gravity" should make for some amazing motion pictures set in space and other exotic environments.

After the last fade to black, what you keep is the story. "Gravity" tells a hefty one with a whole lot of heart.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Dave Brody has been a writer and Executive Producer at SPACE.com since January 2000. He created and hosted space science video for Starry Night astronomy software, Orion Telescopes and SPACE.com TV. A career space documentarian and journalist, Brody was the Supervising Producer of the long running Inside Space news magazine television program on SYFY. Follow Dave on Twitter @DavidSkyBrody.