In early October, the mid-evening (9 to 10 p.m.) sky is in transition.

Many of the constellations and rich Milky Way star fields of summer evenings past are still very much in evidence in the western heavens, while the brilliant yellow-white star Capella ascending from low in the northeast is a promise of even more dazzling stars to come. In another couple of months, Orion and his retinue will be dominating the eastern sky as we approach the start of another winter season.

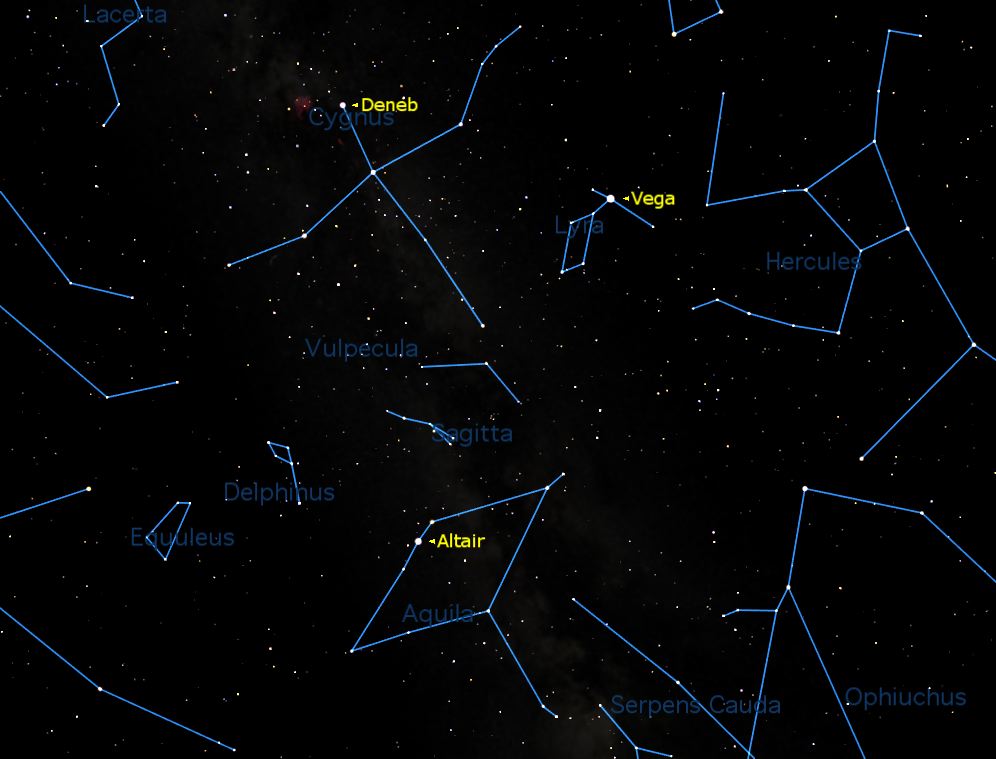

Still very well placed for viewing high in the southwest sky is the famous "Summer Triangle," a large, roughly isosceles figure composed of three of the 21 brightest stars in the sky: Vega, Altair and Deneb. [Night Sky: Visible Planets, Moon Phases & Events, October 2013]

Interestingly, at this time of year, the stars still maintain their steady drift westward and set four minutes earlier each night, but this is somewhat compensated by the fact that darkness is coming rapidly earlier every night – during October as seen from mid-northern latitudes, the sun is setting about 1 1/2 minutes earlier each night, so the star positions appear to be only slightly displaced.

Case in point: The position of the stars at 9:30 p.m. local daylight time this week will have changed little as seen at 6:30 p.m. local standard time during the first week of November. It might seem odd that a star pattern so closely identified with balmy summer nights is still in plain view high in the sky at nightfall on chilly mid-autumn evenings, but take advantage of these circumstances. Unlike the summer, when nights are often hazy across the northern tier of the United States, football weather brings many clear, crisp nights with far better observing conditions.

A milky split

Using binoculars, try sweeping through the Summer Triangle and explore the beautiful star clouds of the "summer" Milky Way.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

From a location far from the glare of bright city lights, the view of this section of the sky is nothing short of breathtaking. Try to take it all in with just the naked eye and you’ll soon become aware of an enormous dark lane running south along the Milky Way from Deneb and then practically midway between Vega and Altair.

This is the famous splitting or "bifurcation" of the Milky Way, which provides clear evidence that some parts of interstellar space are far from transparent. The split is caused by thick clouds of interstellar dust positioned along the plane of our galaxy. Such clouds that are so dense that they cut off our view of more distant bright objects are sometimes referred to as dark nebulae.

The neck of the constellation Cygnus (The Swan) runs straight on down through the bifurcation. Cygnus is also popularly referred to as the Northern Cross; the neck of the Swan also serves as the upright of the Cross. Deneb marks the top of the upright, while at the foot of the Cross is a much dimmer star known as Albireo.

I went into greater detail about this star a few months back, but since it’s still in good viewing position, I again urge you to check it out with binoculars or a small telescope; optical aid reveals it to be in actuality a beautiful double star. Look particularly at the striking color contrast between the two components: orange for the primary and diamond blue for the companion.

Speaking of autumn

Of course, since it is autumn there are a number of much dimmer stars of the fall season that cover much of the southern and eastern sections of the sky.

The dim zodiacal constellation Aquarius is very much in evidence over in the southern sky. This star pattern traditionally represents a man holding a water jar (marked by an inverted Y-shaped group of four stars), which is supposedly spilling a vaguely marked stream of water southward into the mouth of Piscis Austrinus, the Southern Fish.

Here we find a somewhat isolated 1st-magnitude star, Fomalhaut, whose identity can be definitively checked by extending a line along the western (right) side of the Great Square of Pegasus about three times its own length.

Fomalhaut announces the arrival of autumn. When you see it hanging low near the southeast horizon at nightfall at this time of year, the turning (and falling) of the leaves have begun.

And when you see Fomalhaut already beginning to sink in the southwest by nightfall in late November, it usually means that the leaves have stopped falling . . . and fall starts leaving.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.