Diamond Rain May Fill Skies of Jupiter and Saturn

Diamonds, the saying goes, are a girl's best friend and Jupiter and Saturn just might be filled to the brim with them, scientists say.

Chunks of diamonds may be floating in hydrogen and helium fluid deep in the atmospheres of Saturn and Jupiter. What's more, at even lower depths, the extreme pressure and temperature can melt the precious gem, literally making it rain liquid diamond, researchers said.

"The new data available has confirmed that at depth, diamonds may be floating around inside of Saturn, some growing so large that they could perhaps be called 'diamondbergs,'" officials from California Specialty Engineering in Pasadena, Calif., wrote in a statement announcing the discovery today (Oct. 9). Planetary scientists Mona Delitsky of CSE and Kevin Baines of the University of Wisconsin-Madison conducted the research. [Amazing photos of monster storm in Saturn's atmosphere]

Diamonds can form when elemental carbon, like graphite or soot created by huge lightning storms on Saturn, falls into the deep atmosphere of the planet where it is crushed into the gem, Baines and Delitsky said. Those solid diamonds then move farther into the depths of the planet, where they turn into a liquid near the core.

Scientists have known that stable diamonds may exist in the relatively chilly cores of Neptune and Uranus, but until now, Jupiter and Saturn were thought too hot to allow for solid, stable diamond formation.

"Diamonds are forever on Uranus and Neptune and not on Jupiter and Saturn," Delitsky and Baines wrote.

In a book called Alien Seas (Springer 2013), Baines and Delitsky detailed the story of how robotic mining ships may eventually be able to roam the interior of Saturn sometime in the future to collect diamonds and return them to Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Although it is still a mysterious process, scientists think that, on Earth, diamonds form naturally when carbon is buried about 100 miles (160 kilometers) below the surface. The future diamond then needs to be heated to approximately 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1093 degrees Celsius) and squeezed under pressure of around 725,000 pounds per square inch. It also needs to quickly move to the Earth's surface — usually catching a ride with some fast-moving magma — to cool down.

The new diamond research was presented today (Oct. 9) at the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences 45th annual meeting in Denver.

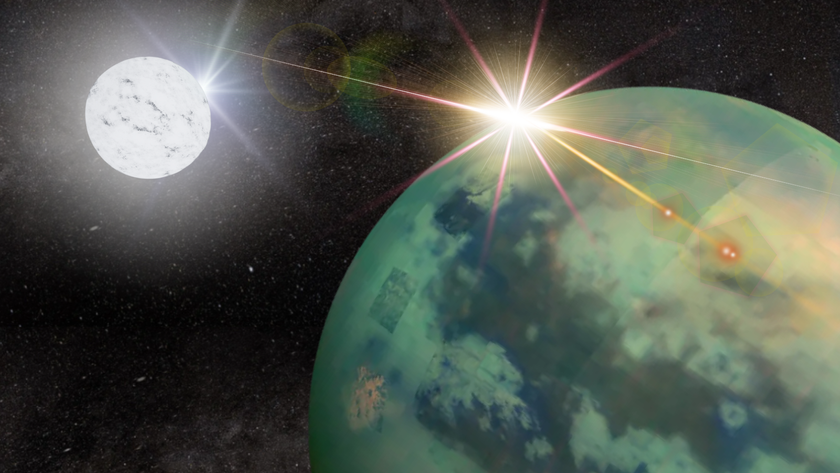

Alien planets could also play host to diamonds. An exoplanet 40 light-years from the solar system is made largely out of diamond, astronomers have said. Scientists think the planet (named 55 Cancri e) is more carbon-rich than Earth, an ideal environment for diamond formation.

A new study from the University of Arizona casts doubt on that conclusion, however. The new research suggests that 55 Cancri e might not be quite so diamond laden because its host star is not as carbon-rich as expected.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.