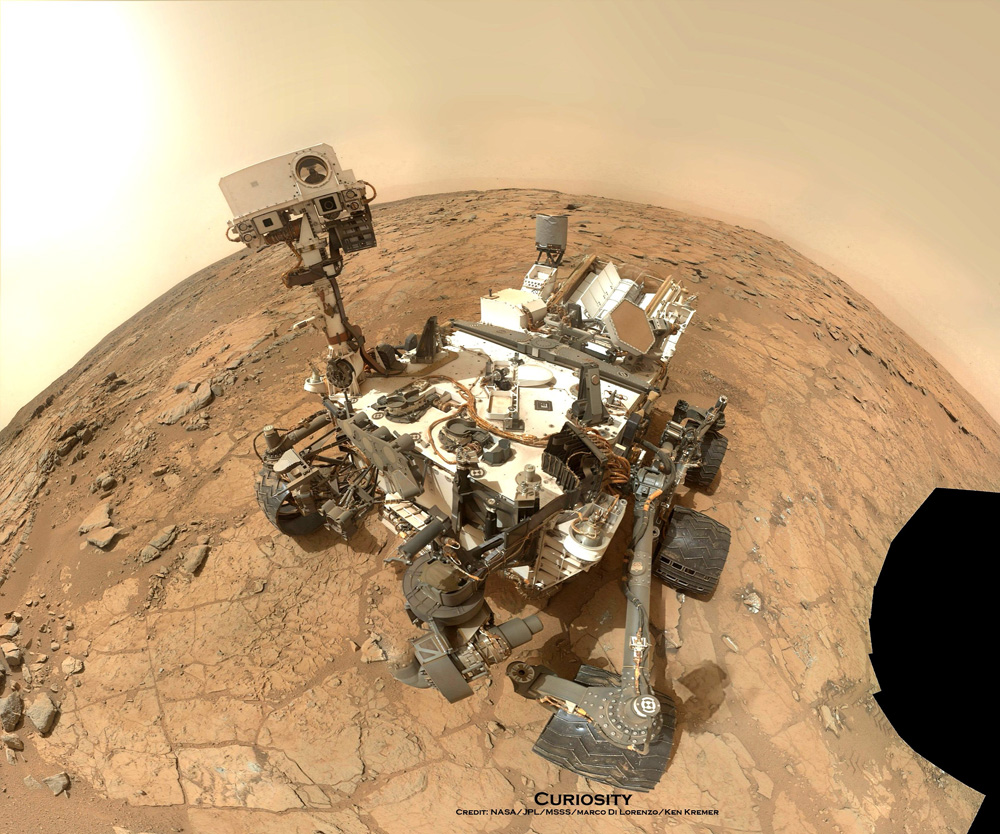

Mars Rover Curiosity Proves Some Earth Meteorites are Martian

Some pieces of rock that fell to Earth from space are indeed from Mars, new measurements reveal.

New data collected by NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has pinned down the exact ratio of two forms of the inert gas argon in the Martian atmosphere. These new measurements will not only help confirm the origins of some meteorites, they could also help researchers understand how and when Mars lost most of its atmosphere, transforming from a warm, wet planet to the red desert it is today.

By understanding exactly how much of the lighter isotope argon-36 is present in the Martian atmosphere and comparing it to the heavier isotope, argon-38, scientists were able to confirm what the composition of a Martian meteorite on Earth should be. [Mars Meteorites: Pieces of the Red Planet on Earth (Photos)]

"We really nailed it," Sushil Atreya of the University of Michigan and lead author of an Oct. 16 paper reporting the finding in Geophysical Research Letters, said in a statement. "This direct reading from Mars settles the case with all Martian meteorites."

Curiosity found that the argon ratio for Mars is 4.2. The lighter form of argon has escaped more readily than the heavier isotope, NASA officials wrote in a statement.

If Mars had not lost atmosphere through the course of its planetary history, its argon ratio would be 5.5 — the same as the sun and Jupiter, two cosmic bodies with so much gravity that isotopes cannot escape, NASA officials said.

Before this new study, scientists had placed the argon ratio somewhere between 3.6 and 4.5 by analyzing gas trapped inside Martian meteors on Earth, but one of Curiosity's precise instruments — called Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) — allowed NASA researchers to find the more exact proportion.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Other isotopes measured by SAM on Curiosity also support the loss of atmosphere, but none so directly as argon," Atreya said. "Argon is the clearest signature of atmospheric loss because it's chemically inert and does not interact or exchange with the Martian surface or the interior. This was a key measurement that we wanted to carry out on SAM."

Although Curiosity is unable to directly investigate how much atmosphere Mars is losing, NASA's next Mars mission is designed to do just that, officials with the space agency said. The MAVEN spacecraft (the name is short for Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution Mission) will launch toward the Red Planet in November.

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has been roaming the surface of the Red Planet since it landed in August 2012.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.