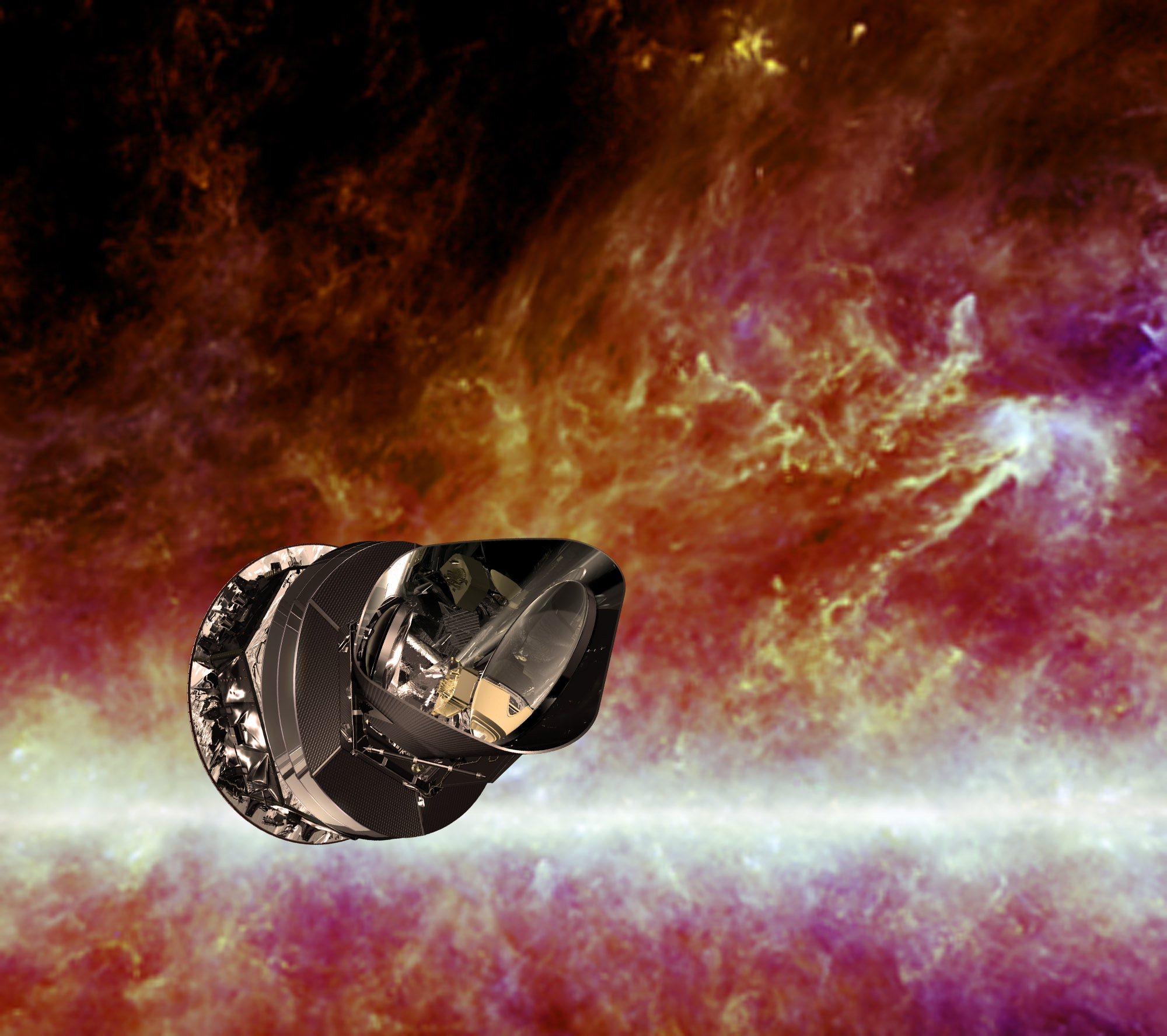

Europe's Planck Space Telescope 'Time Machine' Shuts Down

After hunting for the earliest clues about the evolution of the universe for more than four years, Europe's Planck Space Observatory has gone dark.

Officials with the European Space Agency sent the Planck observatory its final command on Wednesday (Oct. 23), marking the end of its prolific mission. The space observatory launched in May 2009 on a mission to scandeep space for the faint relic radiation called cosmic microwave background — the oldest light in the universe — created 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

ESA officials described the Planck observatory as a sort of cosmic "time machine" because of its ability to peer back into the universe's history. They sent the final command to Planck at 12:10:27 GMT (8:10:27 a.m. EDT) on Wednesday. [Gallery: Planck Spacecraft Sees Big Bang Relics]

"It is with much sadness that we have carried out the final operations on the Planck spacecraft, but it is also a time to celebrate an extraordinarily successful mission," Steve Foley, operations manager for Planck at ESAs European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany, said in a statement.

The Planck telescope's major achievements include piecing together the most accurate map of the cosmic microwave background to date — essentially the best "baby photo" of the universe ever seen. Before this light was created in the universe's infancy, everything was too hot and dense for light to pass though.

Planck's map also helped cosmologists get a better handle on the age of the universe. When researchers unveiled the new picture in March, they said it showed that the universe was 100 million years older than previously thought, bringing its age to 13.82 billion years.

Planck was equipped with two powerful tools: the High Frequency Instrument (HFI), which could detect frequency bands between 30 and 70 GHz, and the Low Frequency Instrument (LFI), which could pick up bands in the range of 100 to 857 GHz. Both instruments completed five full-sky surveys — beyond the original target of two.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The satellite was also outfitted with a high-tech cooling system that allowed the telescope to operate near absolute zero, just one-tenth of a degree above minus 459.67 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 273.15 degrees Celsius). Keeping the sky-mapping instruments at frigid temperatures was necessary to let Planck's sensors detect heat from some of the coldest parts of the universe without being swamped by the spacecraft's own warmth.

In January 2012, the HFI exhausted its supply of liquid helium coolant needed to maintain such cold temperatures. The LFI, meanwhile, had enough coolant to keep making observations until Oct. 3, 2013.

When Planck's mission began winding down in August, the satellite was pushed away from its operational orbit around the Lagrange Point 2 (L2) — a place where the gravity of Earth and the sun roughly balance out — to a long-term orbit around the sun. In the last few weeks, the spacecraft was prepped for hibernation and used up all of its remaining fuel before its transmitter was finally switched off.

Planck was launched with a sibling spacecraft, the Herschel telescope, which ceased scientific work in April and was turned off on June 17.

Though the telescope has been powered down, the wealth of data it collected will be scrutinized by scientists for years to come, mission scientists said.

"Planck has given us a fresh look at the matter that makes up our universe and how it evolved," project scientist Jan Tauber said in a statement, "but we are still working hard to further constrain our understanding of how the universe expanded from the infinitely small to the extraordinarily large, details which we hope to share next year."

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.