Cosmic Lights: Bright Venus, Solar Eclipse Dominate Sky This Week

Editor's Note: For the latest info and skywatching guides for the Nov. 3 solar eclipse, read: Secrets of Sunday's Rare Solar Eclipse Explained

This week marks two celestial events characterized by cosmic objects that are either far apart or very close.

Venus reaches maximum elongation from the sun Friday (Nov. 1) evening, and the moon passes directly in front of the sun, creating a solar eclipse Sunday morning.

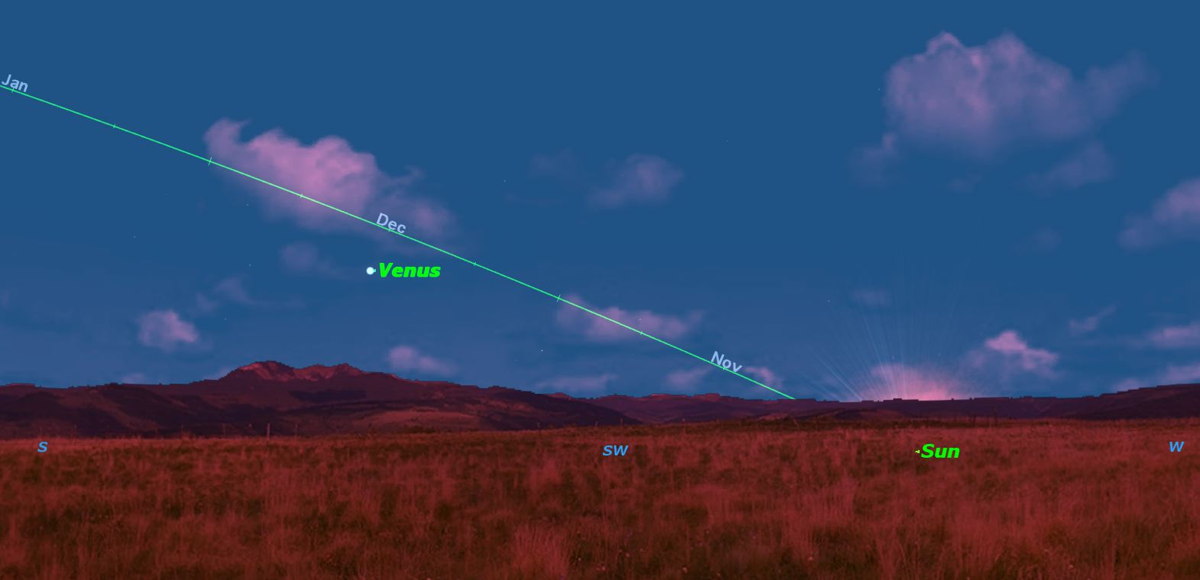

On Friday, Venus reaches a point as far from the sun in our sky as it can get. Because Venus is closer to the sun than the Earth, it never strays very far from the sun in the sky. This week it will be 47 degrees east of the sun, setting in the southwestern sky a little more than two hours behind the sun. [Photos of Venus, the Mysterious Planet Next Door]

Have you seen Venus lately? Although it is the brightest object in our sky after the sun and moon, you may have missed it, especially if you live in the Northern Hemisphere. Usually Venus is a brilliant "evening star," but this year it is playing shy. Because of its current position relative to the sun, it has been unusually hard to see.

The sun, moon, and planets move around the sky on a path called the ecliptic. Because the Earth is tipped 23 degrees to this path, it isn’t parallel to the celestial equator. At present, when the sun sets, this path is tipped down close to the horizon, so that Venus is quite low at sunset.

In addition, Venus is currently quite a bit to the south of this path. The result is that, at sunset, Venus is only about 15 degrees above the horizon. If you have any obstructions on your southwestern horizon, you can easily miss Venus, despite its brilliance.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Venus' position at its greatest elongation has some interesting effects. Because the planet is located at the right angle in a triangle formed by the sun, Venus, and Earth, it is illuminated exactly from the right. Because of this, people on Earth see exactly one half illuminated and one half in shadow. In a telescope, Venus at this time looks like a tiny perfect half moon.

It's actually more perfect than the moon, because instead of a rough cratered surface, Venus shows a perfectly smooth featureless cloud deck.

To the naked eye, Venus is brilliant and pure. In a telescope, it is a perfect half-lit sphere. But underneath these placid clouds lurks a nightmare world.

Because of its dense clouds, Venus provides an example of the greenhouse effect gone mad. Those clouds trap the sun's heat and raise the surface temperature of the entire planet to 867 degrees Fahrenheit (464 degrees Celsius). This is significantly hotter than the melting point of lead, 621 degrees Fahrenheit (327 degrees Celsius).

To make matters worse, Venus' atmosphere is loaded with sulfur dioxide, so the planet's surface is continuously pelted with sulfuric acid rain.

Remarkably, the Soviet Union managed to land several robotic probes on Venus during the 1970s. In 1975, Venera 9 and 10 even returned images from the surface.

The second event this week is a hybrid eclipse of the sun on Sunday. This mostly takes place over the Atlantic Ocean and central and east Africa, but will be visible as a partial eclipse at sunrise over much of northeastern North America.

Even though the sun will be close to the horizon, take all the usual precautions for viewing the sun, such as a #14 welder’s glass. Even though it may appear safe to the eye, the damaging infrared and ultraviolet radiation still penetrates.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.