Editor's Note: In this weekly series, SPACE.com explores how technology drives space exploration and discovery.

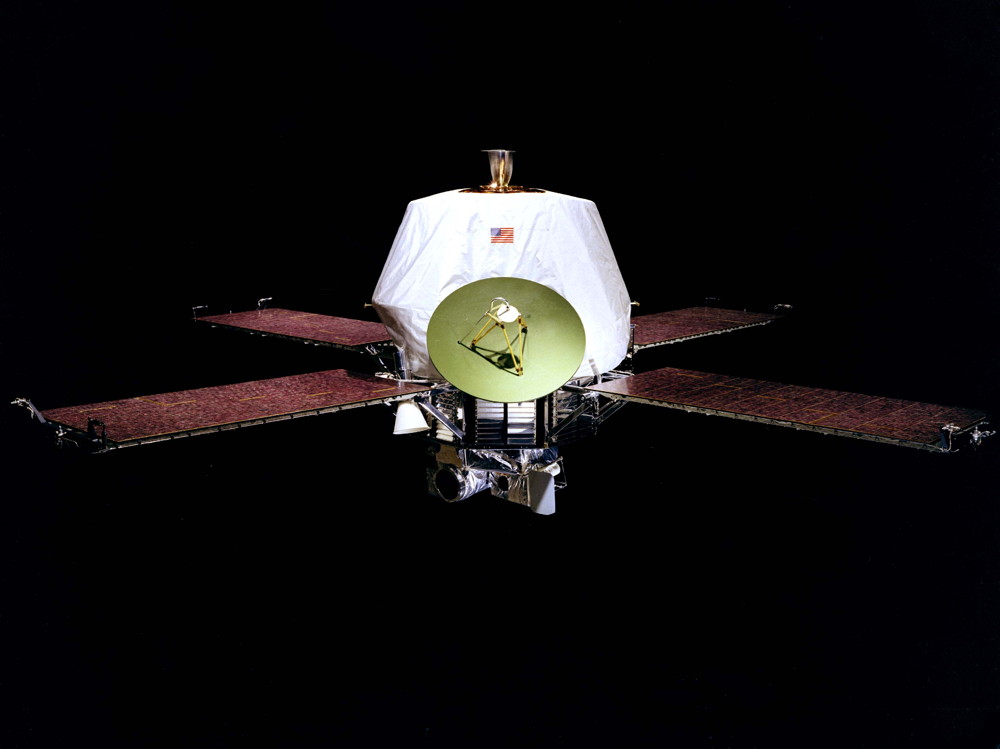

NASA plans to launch its next Mars orbiter today (Nov. 18), kicking off a mission that differs markedly from the space agency's many previous Red Planet efforts.

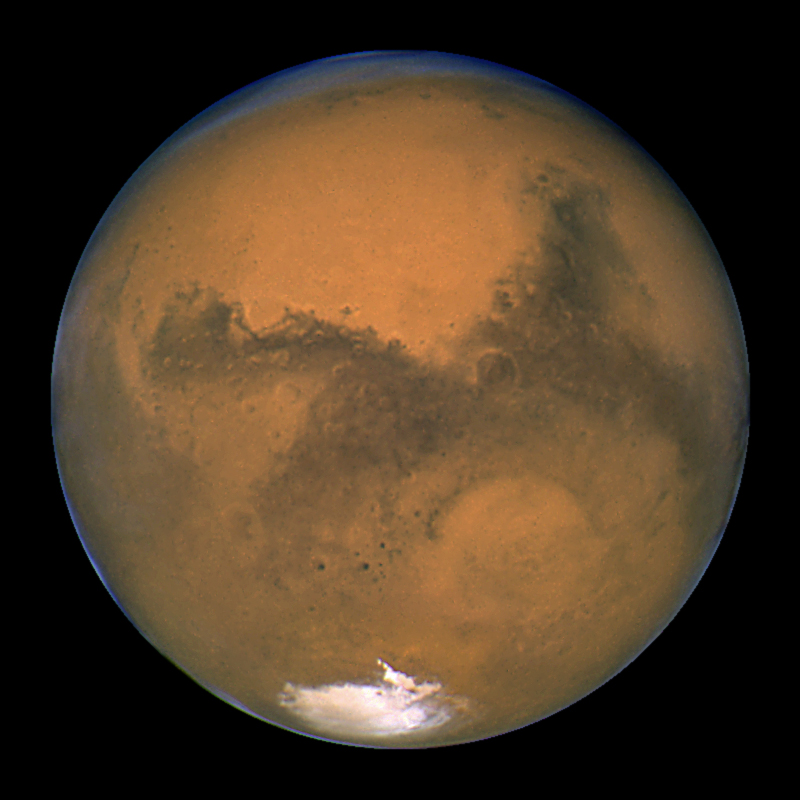

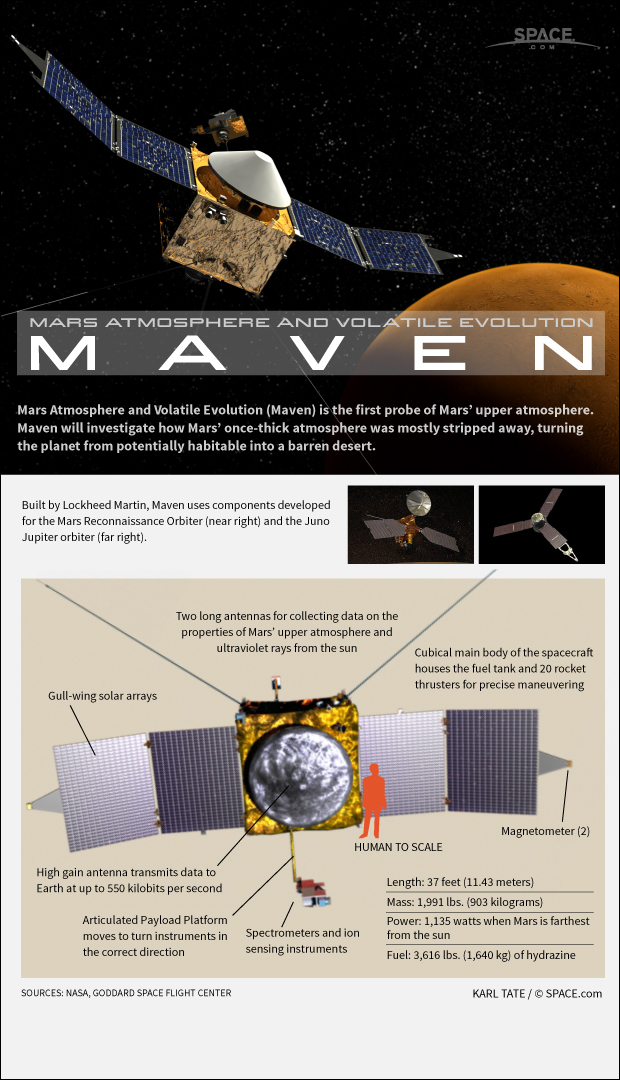

Unlike the nine other orbiters that NASA has blasted toward Mars over the last 40 years, the MAVEN spacecraft — short for Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution — will set its sights on the thin shell of air swirling above the Red Planet's dry and frigid surface. The spacecraft will lift off at 1:28 p.m. EST (1828 GMT) and you can watch the launch live on SPACE.com via NASA TV, beginning at 11 a.m. EST (1600 GMT).

"We're an atmospheric monitoring mission, whereas all the orbiters that come before us have really been surface-mapping, surface-observation-type missions," Guy Beutelschies, MAVEN project manager at Lockheed Martin Space Systems, which built the spacecraft, told reporters Friday (Nov. 15). [NASA's MAVEN Mars Probe: 10 Surprising Facts]

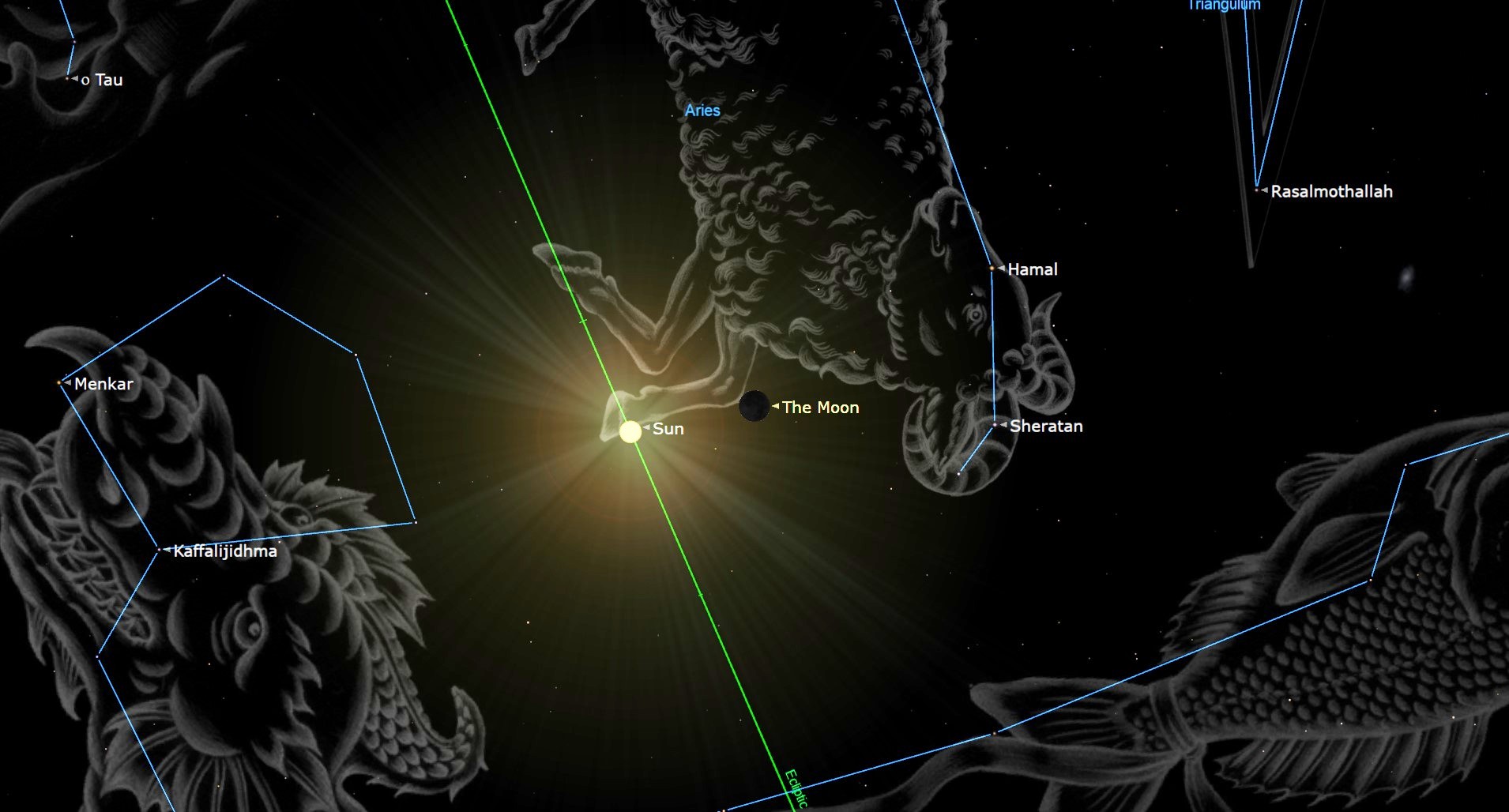

![Since the 1960s, humans have invaded our neighboring planet Mars with swarms of spacecraft. Only about half of the attempts have been successful. See how many robot missions to Mars have launched in this SPACE.com infographic. [See the Full Occupy Mars Infographic]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/axtSHqkGu8QzSEiswjhZ6d.jpg)

A mysterious planet comes into focus

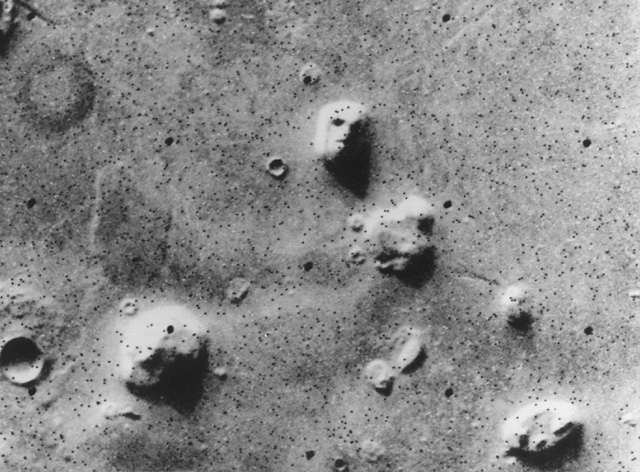

NASA has been sending probes toward Mars since November 1964, when the agency launched the Mariner 3 spacecraft on an attempted Red Planet flyby. That mission failed, but Mariner 4, which blasted off just three weeks later, managed to beam home 21 up-close photos of Mars — the first pictures of another planet ever returned to Earth from deep space.

NASA's first attempt at a Mars orbiter also failed when Mariner 8 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean shortly after liftoff in May 1971. But the space agency made history with Mariner 9, which became the first probe ever to orbit another planet when it arrived at Mars in November 1971.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mariner 9 sent more than 7,300 images back to Earth, allowing researchers to create a global map of the Martian surface. These photos painted the Red Planet in an entirely new light, revealing huge volcanoes, giant canyons and what appeared to be the remnants of ancient riverbeds. The probe also took the first up-close pictures of Mars' two tiny moons, Phobos and Deimos, according to NASA officials.

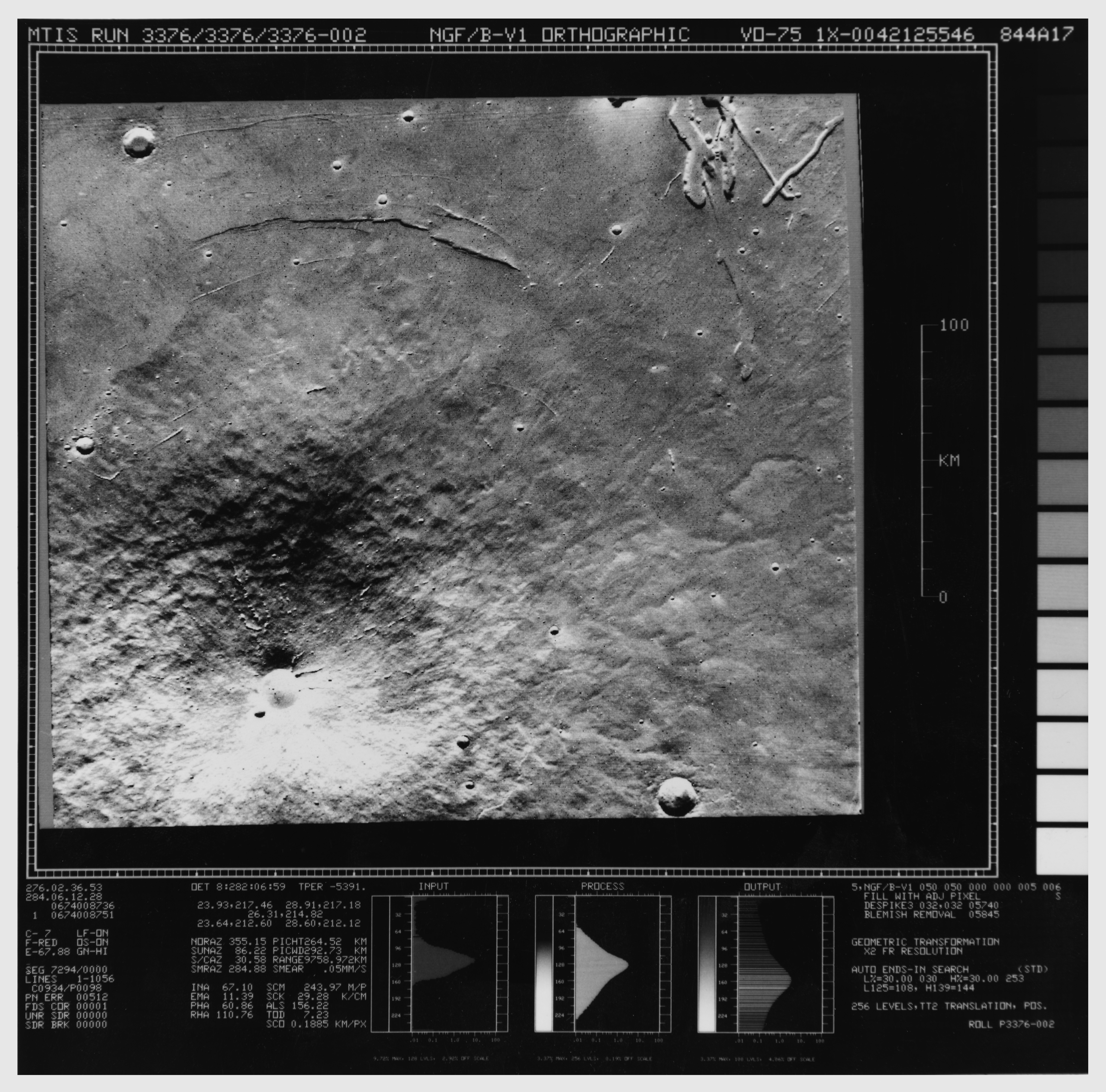

Next up were the twin Viking orbiters, which launched a few weeks apart in 1975. Viking 1 and 2 flew with landers designed to search for signs of Mars life, so part of the orbiters' mission involved supporting these surface craft. But the two orbiters returned a wealth of scientific data in their own right, improving researchers' understanding of the Red Planet's topography and finding evidence that large amounts of water flowed across the Red Planet's surface long ago.

"Volcanoes, lava plains, immense canyons, cratered areas, wind-formed features and evidence of surface water are apparent in the orbiter images," NASA officials write in a summary of the Viking mission. "The planet appears to be divisible into two main regions, northern low plains and southern cratered highlands."

The Viking landers, meanwhile, found no solid evidence of Martian organisms, though researchers are still arguing about the results of their experiments today. [The Search for Life on Mars (A Photo Timeline)]

Taking a closer look

A long lull followed the Viking mission; NASA launched its next Red Planet explorer, an orbiter called Mars Observer, in 1992. The probe failed just before reaching Mars — a fate shared by the agency's Mars Climate Orbiter, which blasted off in December 1998.

But sandwiched between these two ill-fated missions was the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS), which studied the Red Planet for more than nine years after arriving in orbit in September 1997.

The probe used five different instruments to make a host of discoveries about the Red Planet. For example, MGS before-and-after images of two different gullies suggest that liquid water may have flowed on Mars within the last decade or so, NASA officials have said.

Further, the orbiter's laser altimeter helped scientists create the best-ever topographic map of the Red Planet, and readings from its magnetometer indicate that Mars once had a global magnetic field, just like Earth. (Earth has retained its field, but Mars has not.)

NASA's next Red Planet orbiter, Mars Odyssey, eventually wrested the longevity record away from MGS. Odyssey arrived in orbit around Mars in October 2001 and continues to study the Red Planet to this day. [The Boldest Mars Missions in History]

Using its three main science instruments, Odyssey has mapped the global distribution of many minerals and chemical elements across the Martian surface, found evidence of large amounts of buried water ice near the planet's poles and measured the radiation environment in low Mars orbit, which could help NASA plan out future manned missions to the Red Planet.

The probe also serves as a vital communications link, relaying data gathered by NASA's Mars rovers back home to Earth. (The agency currently has two rovers exploring the Red Planet's surface — Opportunity, which landed in January 2004, and Curiosity, which touched down in August 2012.)

NASA's next Mars-circling craft, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, has also enjoyed a long and successful mission.

MRO has been studying the Red Planet with six different instruments since arriving in orbit in March 2006. This gear allows the probe to analyze surface minerals, hunt for underground water, monitor Martian weather and take spectacular up-close images of the planet's surface.

MRO's HiRISE camera (short for High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment) can distinguish Martian objects as small as a dinner table, allowing researchers to study the planet's surface features more completely than ever before. This capability has also helped NASA select suitable landing sites for surface craft, such as the Phoenix lander and Curiosity rover.

Like Odyssey, MRO also serves a vital relay function, helping send information from Opportunity and Curiosity back to the robots' handlers on Earth.

MAVEN joins the ranks

Some of the above missions have gathered data about the Martian atmosphere, which was thick long ago when the Red Planet was relatively warm and wet but has been largely lost to space over the eons. However, the Red Planet's air was not their primary focus.

"There's a heavy emphasis earlier, in other missions, on what's happening on the surface of Mars — what happened to the water and understanding topography and so on," David Mitchell, MAVEN project manager at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., said during the Nov. 15 press conference.

MAVEN's chief goal, on the other hand, is figuring out what happened to the Red Planet's atmosphere. The probe will use its eight science instruments to study the solar wind and Mars' upper atmosphere, discerning its composition and how quickly its volatile compounds are escaping into space.

"We collectively, as a team, came up with instrumentation that really goes after, ultimately, the question that we're on, which is the climate — what's happened in the history of Mars?" Mitchell said. "Why did it go from a wetter, Earth-like environment with a thicker atmosphere to where it is today?"

Not just NASA

Not all Mars-orbiting spacecraft have flown American flags over the years, of course. The Soviet Union had a very active Mars program in the 1960s and '70s and succeeded in placing three spacecraft in orbit around the Red Planet between 1971 and 1974.

These probes — known as Mars 2, Mars 3 and Mars 5 — returned a total of 120 images of the Red Planet and gathered data about Mars' gravity and magnetic fields. (Many Soviet/Russian Mars efforts have failed over the years, most recently 2011's Phobos-Grunt mission to Phobos, which never made it out of Earth orbit.)

Europe has a robotic ambassador circling the Red Planet as well. The European Space Agency's Mars Express probe continues to image and study the surface of the Red Planet and gather data about the Martian atmosphere today, nearly 10 years after arriving in orbit around Mars.

On Nov. 5, India launched its first interplanetary probe, the Mars Orbiter Mission, on a mission to probe the Red Planet. Like MAVEN, the Indian Mars probe will arrive at Mars in September 2014 if all goes well.

Visit SPACE.com for the latest MAVEN news, photos and videos. You can also follow MAVEN coverage through the Mission Status Center at SPACE.com's partner, Spaceflight Now.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.