If there were ever a planet with an unfair reputation for its inability to be readily observed, it would have to be Mercury, which is known in some circles as the "elusive planet." But over the next two weeks, skywatchers will have an excellent opportunity to see Mercury in the early morning dawn sky.

Mercury is often cited as the most difficult of the five brightest naked-eye planets to see, because it is the planet closest to the sun. As such, it never strays too far from the sun’s vicinity in our sky.

Mercury is called an "inferior planet" because its orbit is nearer to the sun than the Earth's orbit. From our vantage point, it always appears to be in the same general direction as the sun. Thus, relatively few people have set eyes on it; there is even a rumor that the great Polish astronomer, Nicolaus Copernicus, never saw it. [Mercury Quiz: How Well Do You Know the Innermost Planet?]

Yet, it's not particularly hard to see Mercury. You simply must know when and where to look, and find a clear horizon.

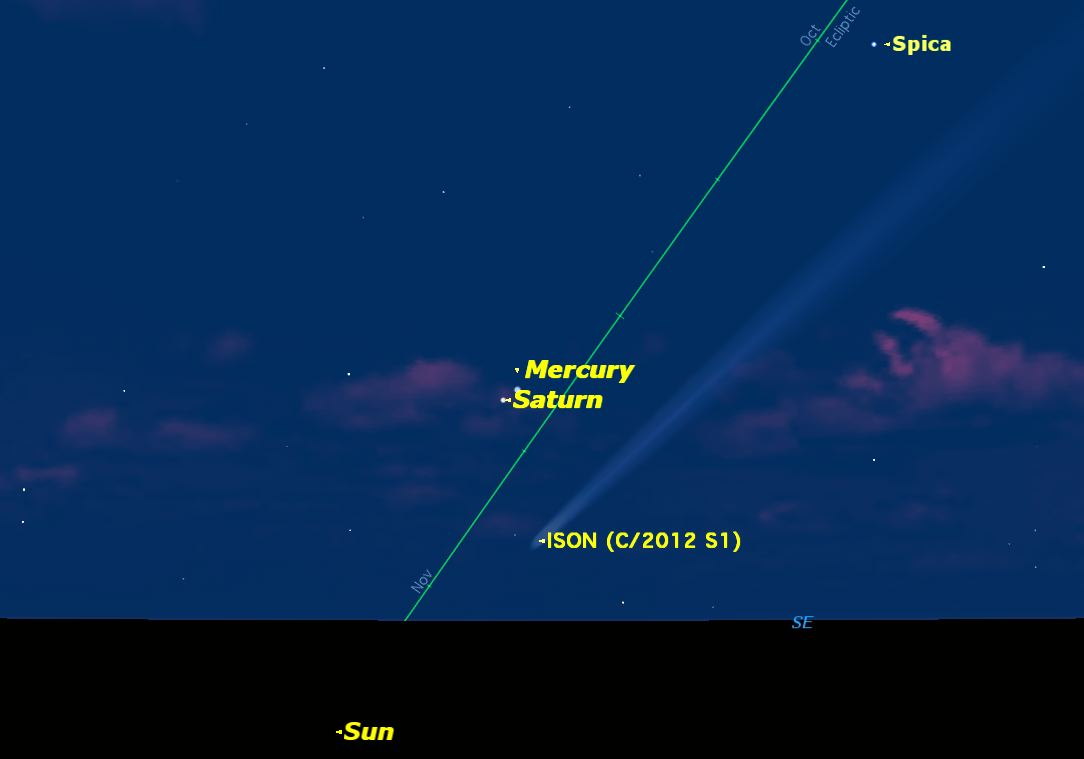

Mercury was very near to the sun on Nov. 1. In its orbit, Mercury crossed to the north side of the ecliptic, or the sun's apparent path, on Nov. 3 (a boon to observers in the Northern Hemisphere). The planet reached perihelion — its closest point to the sun — four days later, when its angular motion around the sun was greatest. This combination of geometries is what suddenly brought this speedy planet into view in the morning sky.

If you are an early riser, it's possible you may have stumbled across Mercury on your own recently. Since Nov. 12, it has been rising at least 90 minutes before sunrise, which is also just about the same time that morning twilight is beginning. If you scan low along the east-southeast horizon about 45 minutes before sunrise, Mercury is visible as a distinctly bright, yellowish-orange "star." [Stargazer Photos: Amazing November Night Sky Views]

This past weekend, Mercury rose more than 100 minutes before the sun, even before the break of dawn. This means, for a short while, Mercury will be visible against a completely dark sky.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

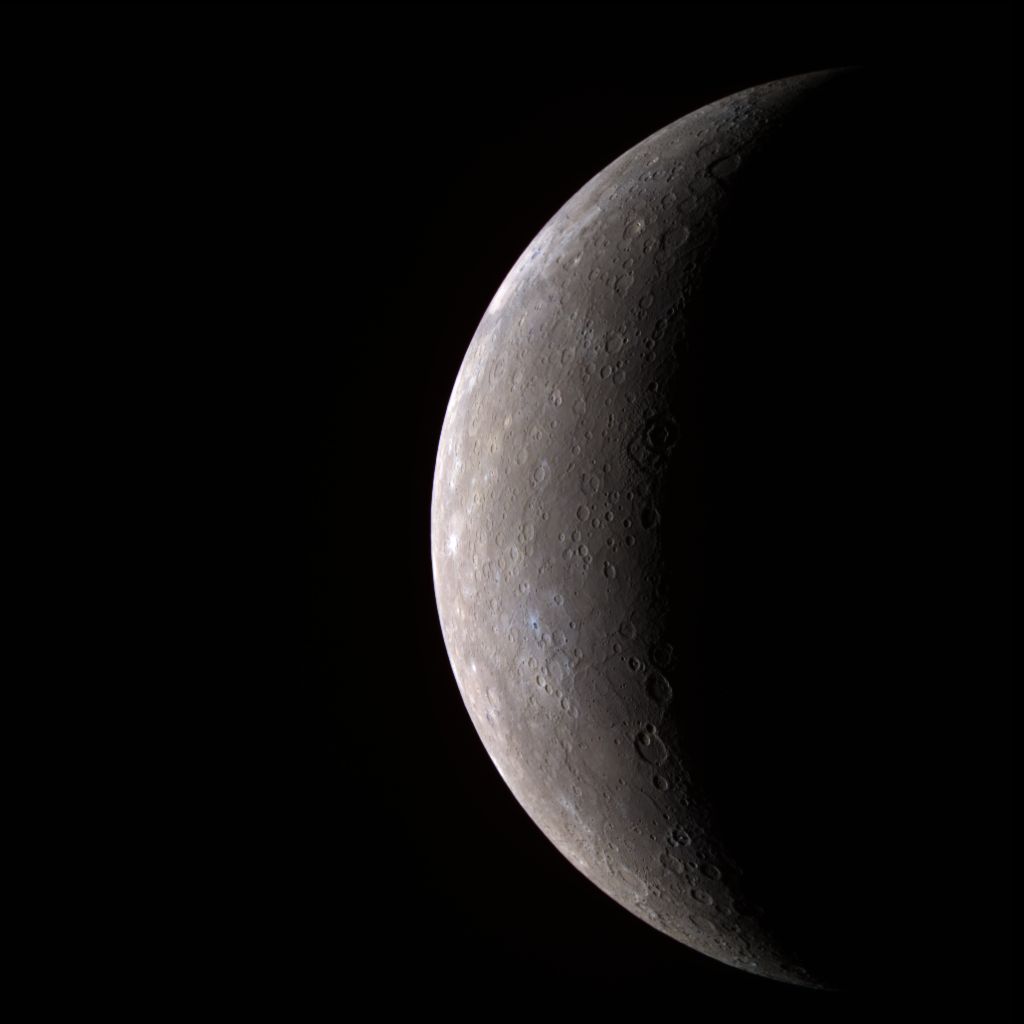

Mercury's greatest western elongation, or its greatest angular distance from the sun in the sky, occurred Monday morning (Nov. 18), with the planet appearing a full 20degreesfrom the sun. Mercury, like Venus, appears to go through phases like the moon. Soon after it moved into the morning sky, Mercury was just a skinny crescent.

Currently, the planet appears roughly half-illuminated and the amount of its surface illuminated by the sun will continue to increase in the days to come. The phases are best viewed by aiming a telescope at Mercury and tracking it through sunrise, to bring the planet higher in the sky.

Although it will begin to turn back toward the sun's vicinity this week, it will brighten a bit more, which should help keep it in easy view over the next couple of weeks.

Toward the end of November, Mercury will increase in brightness to magnitude –0.6. Astronomers refer to the magnitude of a star or planet to determine how bright an object appears in the night sky. Put simply, the lower the magnitude of an object, the brighter it appears in the sky. Among stars, only Canopus and Sirius are brighter than magnitude -0.6. At the end of the month, Mercury should still be relatively easy to find, low in the east-southeast sky about 45 minutes before sunrise.

Here comes Saturn

Near the end of the month, Mercury will also have a close encounter with another bright planet: Saturn.

Like two ships passing in the twilight, Mercury will approach the ringed planet Saturn during the final week of November. Mercury will appear to fall back toward the sun, while Saturn will appear to climb out of the solar glare. The two planets will appear closest together on Nov. 26.

We will have more to say about this "dynamic duo" later this month.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing photo of Mercury or any other night sky object, and you'd like to share it for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+. Original story on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.