International Space Station: 15 Facts for 15 Years in Orbit

A new type of "sunrise" dawned above Earth on Nov. 20, 1998, with the launch of the first piece of the International Space Station.

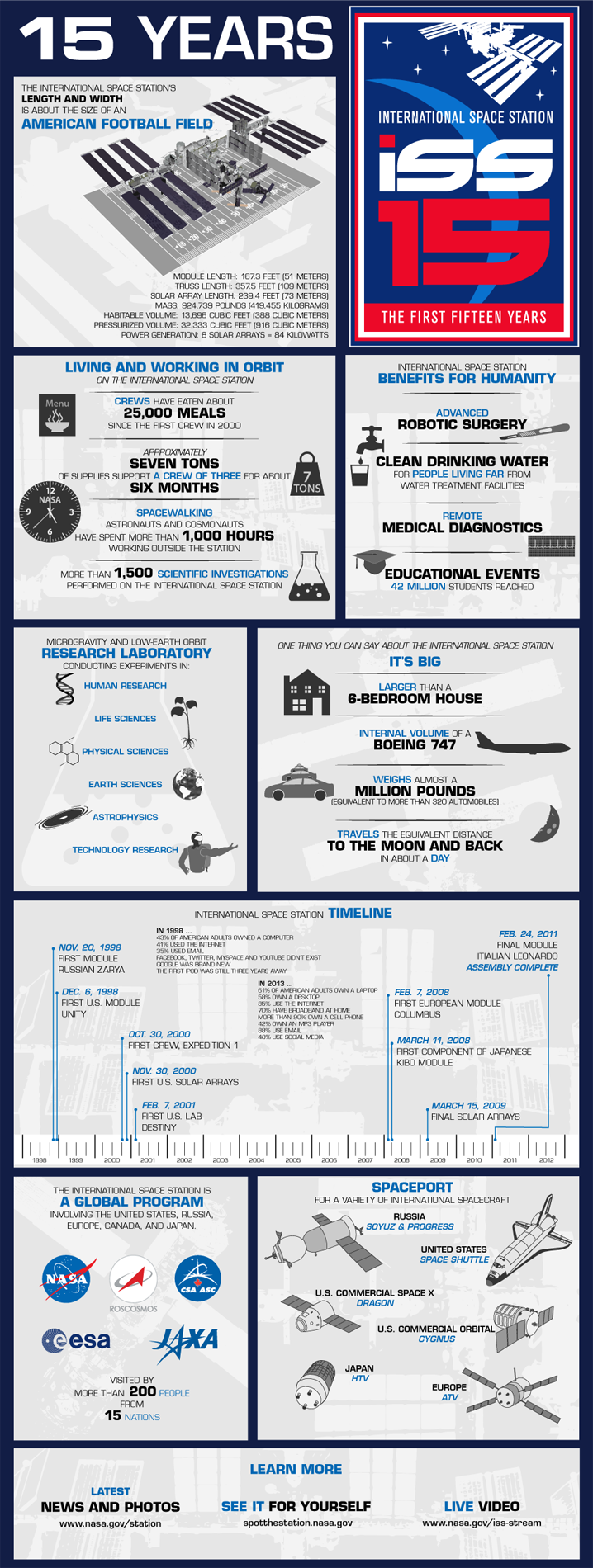

Fifteen years ago Wednesday (Nov. 20), the Russian-built Zarya, or "Sunrise," module, also known as the functional cargo block (FGB), lifted off atop a Proton rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan to begin the most complex scientific and engineering project in history.

Zarya supported orientation control, communications and electrical power for the emerging outpost. Two weeks after its launch, Zarya was joined on orbit by Unity, the station's first connecting node. [Building the International Space Station (Photos)]

It would take 13 years for the space station's assembly to be declared "complete," although it is still being expanded. Today, the station is an active laboratory with hundreds of science experiments being conducted onboard, advancing humanity's knowledge about how to live in space and how to improve life on Earth.

To mark the 15th anniversary, SPACE.com partner collectSPACE.com compiled a countdown of 15 facts about the International Space Station.

15 Sunrises, sunsets

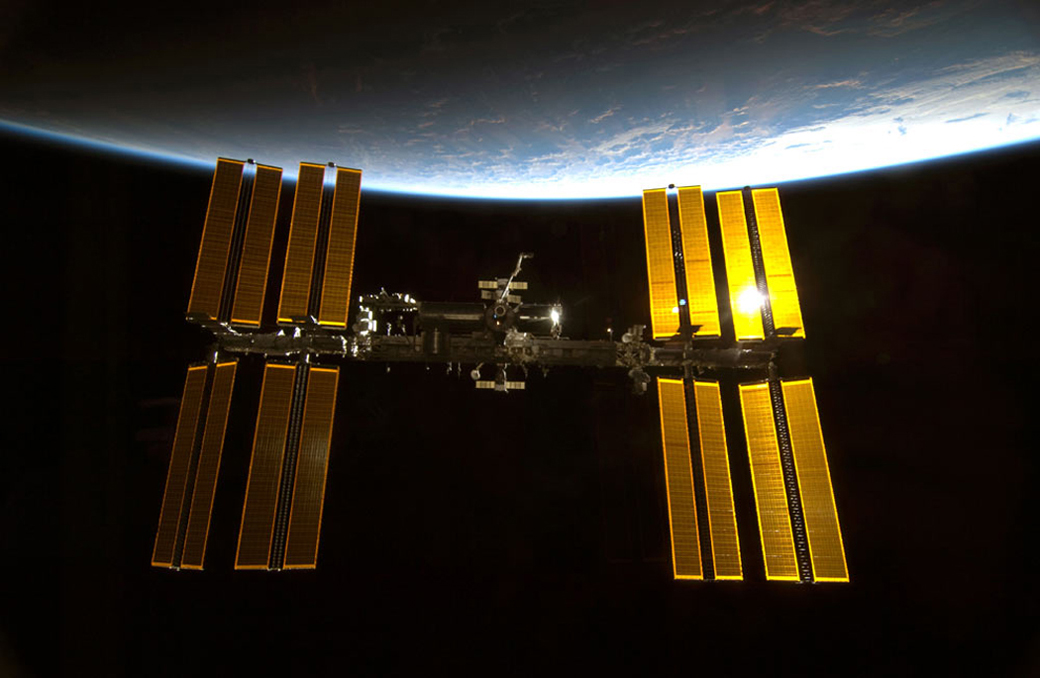

Circling Earth at 17,500 miles per hour (28,000 kilometers per hour) every 92 minutes, the crew members aboard the International Space Station "experience 15 or 16 sunrises and sunsets every day," NASA's Earth Observing System (EOS) Project Office describes.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The whole station glows with the light of dawn," Canadian astronaut and former ISS commander Chris Hadfield told NPR in a recent interview. "You can see the dawn come across the world towards you."

"Then you go back to work and wait another 92 minutes, and it happens again. It's not to be missed, and I tried to watch as many sunrises and sunsets as the work would allow," he said.

Since the launch of the first "Sunrise" (Zarya), the station has "seen" more than 175,000 sunrises and sunsets.

14 Rooms

The space station today has more livable room than a six-bedroom house — spread across 14 pressurized modules or components.

There are three laboratories — the U.S. Destiny module, European Columbus module and Japan's Kibo lab — and three connecting nodes (Unity, Harmony and Tranquility). On the Russian side, there are two docking compartments (Pirs and Rassvet), the Zarya FBG and Zvezda service module. [15 Years of Space Station Science and Construction (Video)]

Quest serves as the U.S. operating segment's airlock and the Leonardo permanent multipurpose module (PMM) acts as a closet for storage space. The Kibo module also has its own supply closet (the "JLP") and lastly is the Cupola, a seven-windowed observatory.

The space station's internal volume is about the same as a Boeing 747 jumbo jetliner.

13 Years of continuous residency

It took two years of construction before the space station was ready for tenants. The three-member Expedition One crew, NASA astronaut William Shepard and cosmonauts Sergei Krikalev and Yuri Gidzenko, arrived at the orbiting outpost on Nov. 2, 2000, and the space station has been continuously occupied ever since.

Initially, the station's crew was limited to three people, and for a period of time, that was reduced to only two. Today, the Expedition 38 crew has six members.

Over the past 4,766 days (as of Nov. 20), 88 people have lived aboard the space station as resident crew members, with another 120 or so people visiting the orbiting outpost to help with construction and deliver supplies.

12 Months for the first yearlong mission

To date, the longest expedition on board the International Space Station was 215 days and 8 hours, logged by the Expedition 14 crew of Michael Lopez-Alegria and Mikhail Tyurin from September 2006 to April 2007. Their seven months in space was one and a half months longer than the typical resident crew's stay, which averages about five and a half months in duration.

But as attention turns to sending astronauts out into the solar system, NASA and its international partners are now preparing for the first yearlong stay on the space station.

Beginning in March 2015, NASA astronaut Scott Kelly and Roscosmos cosmonaut Mikhail Korniyenko will live and work on the orbiting complex for 12 months. Their stay will further inform scientists' understanding of how the human body reacts to extended exposure to microgravity.

11 Hundred hours spacewalking

Earlier this month, two cosmonauts ventured outside the space station to mount a camera platform and perform a symbolic relay holding an Olympic torch. It was the 174th spacewalk in the space station's history, bringing the total time spent on ISS extravehicular activities (EVA) to 1,094 hours and 39 minutes, or 45.6 days.

"I remember pre-ISS talking about the hundreds, or more than one hundred, EVAs that are going to be required for assembly [of the space station] and thinking that was a huge mountain to climb," ISS Expedition 16 astronaut Dan Tani said in December 2007 after completing the station's 100th spacewalk.

One hundred and thirteen (113) expedition crew members have donned either U.S. EMU or Russian Orlan suits to work on assembling and maintaining the space station.

10 Space agencies sending astronauts

Fifteen nations partnered to build the International Space Station — the U.S., Russia, Japan, Canada and members of the European Space Agency (ESA) — but the people who have visited the ISS have not been limited to those countries.

In addition to NASA, Roscosmos, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), Canadian Space Agency and ESA, astronauts have visited the outpost representing five other space agencies, including France's CNES, Brazil's AEB, Malaysia's Angkasa, South Korea's KARI and Italy's ASI.

9 Hundred, 25 thousand pounds in orbit

When Zarya launched in 1998, it weighed 42,600 pounds (19,300 kg). A decade and a half later, the International Space Station now masses almost one million pounds — 925,000 pounds (420,000 kg).

The station is the largest spacecraft ever assembled or flown in space, spanning the length and width of an U.S. football field.

8 Space tourist flights

Not every individual to fly to the station did so under the auspices of a country or space agency. Seven so-called "space tourists," or "spaceflight participants," funded their own multimillion dollar trips to the space station under an agreement with Roscosmos and the U.S. space tourism agency Space Adventures. [The International Space Station: Inside and Out (Infographic)]

California businessman Dennis Tito was the first to pay his own way to the station in 2001. Following Tito into orbit were South African software developer Mark Shuttleworth, New Jersey entrepreneur Gregory Olsen, Iranian-American engineer Ahousheh Ansari, Hungarian-American Microsoft Office inventor Charles Simonyi, second-generation U.S. astronaut and computer game pioneer Richard Garriott and Canadian Cirque du Soleil co-founder Guy Laliberte.

Simonyi enjoyed his first space trip in 2007 so much that he returned for another flight two years later.

7 Visiting vehicles

Zarya's launch began the effort, but it wasn't until NASA's space shuttle delivered and mated the Unity module that the International Space Station was really born.

The shuttle fleet was critical to the assembly of the space station, delivering to orbit the truss segments that formed the outpost's backbone, as well as most of the modules. When the ISS was completed, the orbiters were retired.

Six other spacecraft have and continue to supply and staff the station.

Since Expedition 1 in 2000, Russia's Soyuz has been the primary means for astronauts and cosmonauts to travel to and from the outpost. Similarly, the station's primary cargo craft has been Russia's unmanned Progress craft, which on Nov. 25 will lift off for the 53rd flight to the station.

JAXA's H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV) and ESA's Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) have each resupplied the station four times to date.

Most recently, NASA has contracted with U.S. companies SpaceX and Orbital Sciences to send cargo to the space station on their Dragon and Cygnus vehicles, respectively. Moving forward, the U.S. space agency is also planning to hire private spacecraft to fly its astronauts to and from the space station, with flights starting in 2017.

6 Sleep stations

Although the space station is often compared (including in this article) to the volume of a six-bedroom house, the ISS does not include traditional bedrooms for its resident crew. Rather, six phone-booth-size pods serve as sleep stations and private space for each astronaut and cosmonaut.

"Originally, they were going to put us all in one habitation module with sleep stations all around it, but the way the station was eventually built, we have sleep stations inside [Unity] Node 2, which is in the forward part of the station, and inside the service module, which is in the aft," Chris Hadfield described in a video he filmed about sleeping in space.

"Inside each one is just a sleeping bag tied to the wall. You might think it's uncomfortable not having a mattress and a pillow but without gravity, you don't need anything to hold you up. You can just completely relax and you don't even need a pillow," said Hadfield.

Continue the countdown at collectSPACE.com to read the remaining five facts about the International Space Station’s first 15 years in orbit.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2013 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.