Could Incoming Comet ISON Lose Its Tail to a Thanksgiving Sun Storm?

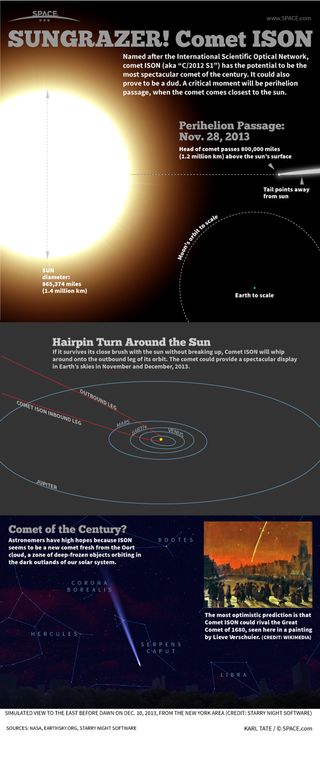

It's difficult to predict exactly what will happen when the potentially great Comet ISON makes a sharp turn around the sun on Thanksgiving Day (Nov. 28). But one thing is certain: The journey will be dangerous.

At less than 730,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from the sun's surface, solar eruptions could rock the icy comet. Experts with NASA say lessons from another comet's tail-clipping encounter with the sun in 2007 presents a forbidding example of what could happen to Comet ISON.

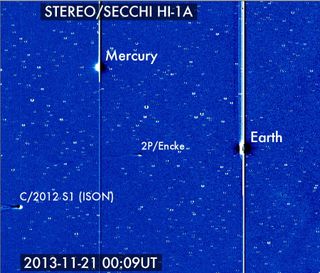

That lesson comes from Comet Encke, which faithfully completes one orbit around the sun every 3.3 years and is one of the most studied comets in history. When it approached the sun in 2007, a coronal mass ejection, or CME, burst from our star and struck the comet, tearing off its tail. NASA's STEREO spacecraft captured images of the violent encounter as this video animation of the comet shows.

The U.S. Naval Research Lab's Angelos Vourlidas, who is participating in NASA's Comet ISON Observing Campaign (CIOC) explained why Comet ISON, at about 30 times closer to the sun than Comet Encke, could face an even worse fate. [Photos of Comet ISON: A Potentially Great Comet]

"For one thing, the year 2007 was near solar minimum," Vourlidas said in a statement from NASA. "Solar activity was low. Now, however, we are near the peak of the solar cycle and eruptions are more frequent."

Vourlidas was referring to sun's 11-year weather cycle. The solar maximum is typically marked by an increase in sunspots, the dark, temporary regions on the sun's surface that can give rise to CMEs.

When Comet ISON approaches the sun, it might be headed for a "hot zone" of CMEs, said Karl Battams, an astronomer at the Naval Research Lab who is also watching the comet. On Thursday, Comet ISON is expected to pass over the sun's equator on the same side of a recently active cluster of sunspots.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I would absolutely love to see Comet ISON get hit by a big CME," Battams said in a NASA statement. "It won't hurt the comet, but it would give us a chance to study extreme interactions with the comet's tail."

Because the gas inside a CME is not very dense, the impact of this magnetized cloud of plasma would not be strong enough to tear apart a comet's core, according to NASA. A CME could, however, yank the comet's fragile tail.

And while the CME that hit Comet Encke back in 2007 was quite slow, Vourlidas believes a CME slamming into Comet ISON could have a more dramatic effect.

"Any CME that hits Comet ISON close to the sun would very likely be faster, driving a shock wave with a much stronger magnetic field," Vourlidas explained in a statement. "Frankly, we can't predict what would happen."

Both Comet ISON and Comet Encke are in the field of view STEREO-A's Heliospheric Imager, their tails waving back and forth with the solar wind. According to NASA, it is possible that both could be hit by the same CME, which would give researchers a chance see how these objects would react to widely separated locations

While ISON has slipped out of view for skywatchers on the ground, NASA's space-based fleet of solar observatories will be watching when ISON's close encounter, including STEREO-A and STEREO-B, the Solar Dynamics Observatory and the Solar and Heliophysics Observatory.

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing picture of Comet ISON or any other night sky view that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

You can follow the latest Comet ISON news, photos and video on SPACE.com.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.