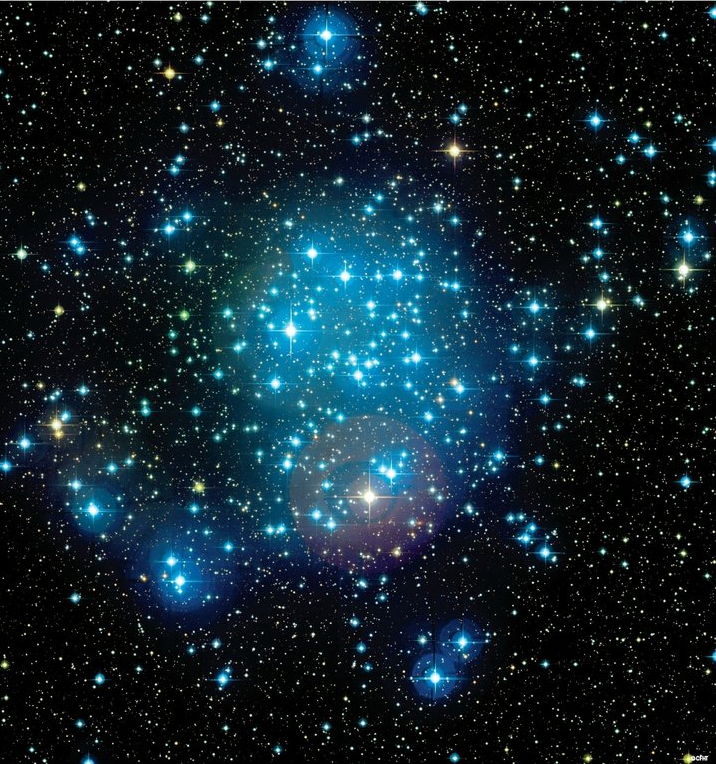

Winter Star Clusters Dot Milky Way Like Ornaments

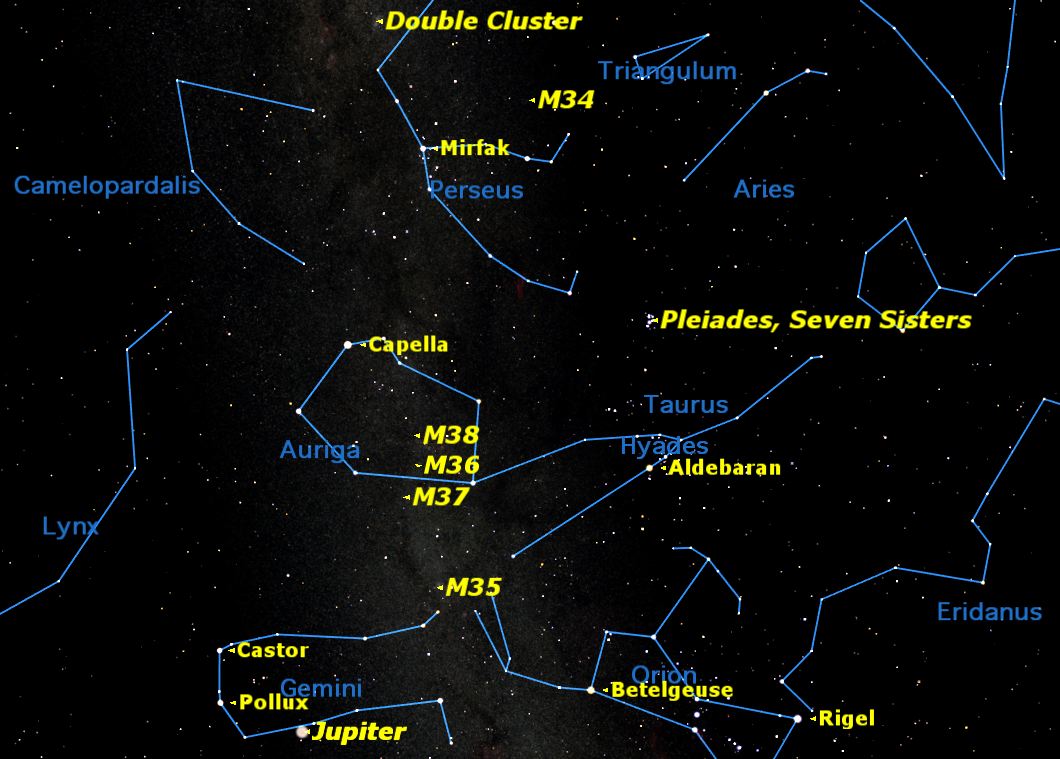

Now that autumn is fading into winter, the beautiful winter Milky Way is coming into view in the eastern sky. Though you need a dark country sky to see the Milky Way itself, even the city-bound stargazer can view many of the star clusters that decorate it like ornaments on a Christmas tree.

Stars are not born in isolation. Usually they form as a group within a cloud of gas and dust. For instance, such a star cluster is forming in the Orion Nebula, where the newly born stars and the nebula from which they form are visible simultaneously. Later in a star cluster's history, the gas and dust has dissipated, leaving a naked cloud of newborn stars.

Some of these newborn clusters are so close to Earth that they can easily be seen with the naked eye. The most famous of these is called the Pleiades, named after seven sisters in Greek mythology. This is the most easily spotted deep-sky object, and was noticed by many different cultures, each of which developed their own mythology around them. For example, in Japan this cluster is known as Subaru, and gives its name to a giant telescope in Hawaii and a line of automobiles. Look closely at the logo on a Subaru car, and you will see the brightest stars of the Pleiades. [See Amazing Night Sky Photos by Stargazers: November 2013]

It is odd that the Pleiades are sometimes called "the seven sisters," because most people can see only six stars in this cluster. This is probably a case of reality being adjusted to fit the legend, with seven being a much more interesting number than six. Binoculars reveal hundreds more fainter stars in this cluster.

The Pleiades lie 410 light-years away from the sun, and are easily visible because their stars are bright and closely packed. But they are not the nearest star cluster; that honor goes to the Hyades, only 150 light-years away.

Because they are nearer, the Hyades are appear to be spread across a wider area of sky, so they are not as obvious as the Pleiades. They are best appreciated in a dark country sky, or through binoculars. The jewel in the Hyades is the red giant star Aldebaran. Its presence in the Hyades is an accident of perspective, since it is actually much closer to Earth than the cluster itself, only 65 light-years away. It just happens to lie in our line of sight, slightly less than half the distance to the Hyades.

With ordinary binoculars, there are many more star clusters in this part of the sky awaiting observers' discovery. Star clusters are the easiest deep-sky objects for the beginner to see, and provide fine views in binoculars and small telescopes even in light-polluted city skies.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Several such clusters are associated with the constellation Perseus. In fact, most of the brightest stars in this constellation, surrounding the star Mirfak, are part of another nearby cluster 600 light-years away, named simply "the Perseus Cluster." Perseus is also the home of the beautiful Double Cluster, two clusters located close together in the sky but lying at different distances from Earth, 7,000 and 8,100 light-years away. It's surprising that Charles Messier missed these bright clusters in his catalog, while catching the much less prominent Messier 34 cluster.

Auriga is another constellation rich in open clusters. Messier catalogued three of the brightest as numbers 36 through 38. All of these make fine sights in a small telescope, and are easily located because they are close to the brilliant star Capella. Just below these, at the feet of the Gemini twins is Messier 35, one of the finest telescopic sights in the sky.

While the dedicated observer will seek out and identify these individual gems, even the most casual skygazer can simply sweep along the Milky Way with binoculars and enjoy this treasure trove of celestial jewels. Start just to the right of Jupiter, and follow the Milky Way upward to Perseus, high overhead.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.