Universe's Biggest Explosions Shaped by Extreme Magnetic Fields

Scientists have captured their best view yet of how extreme magnetic fields shape superfast jets from the most powerful explosions in the universe.

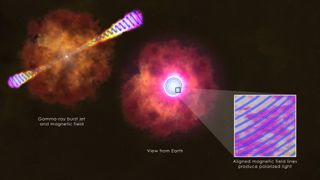

The new research tracked polarized light from cosmic explosions, known as gamma-ray bursts, and offered an unprecedented glimpse into how intense magnetic fields shape the evolution of the outbursts.

"Gamma-ray bursts are the most extreme particle accelerators in the universe," said Carole Mundell, a professor of extragalactic astronomy at Liverpool John Moores University, who led the new study. "They're objects of all kinds of extremes: extreme speeds, extreme gravity, extreme magnetic fields. So they're the ultimate laboratory for testing or laws of physics." [10 Strangest Things in Space]

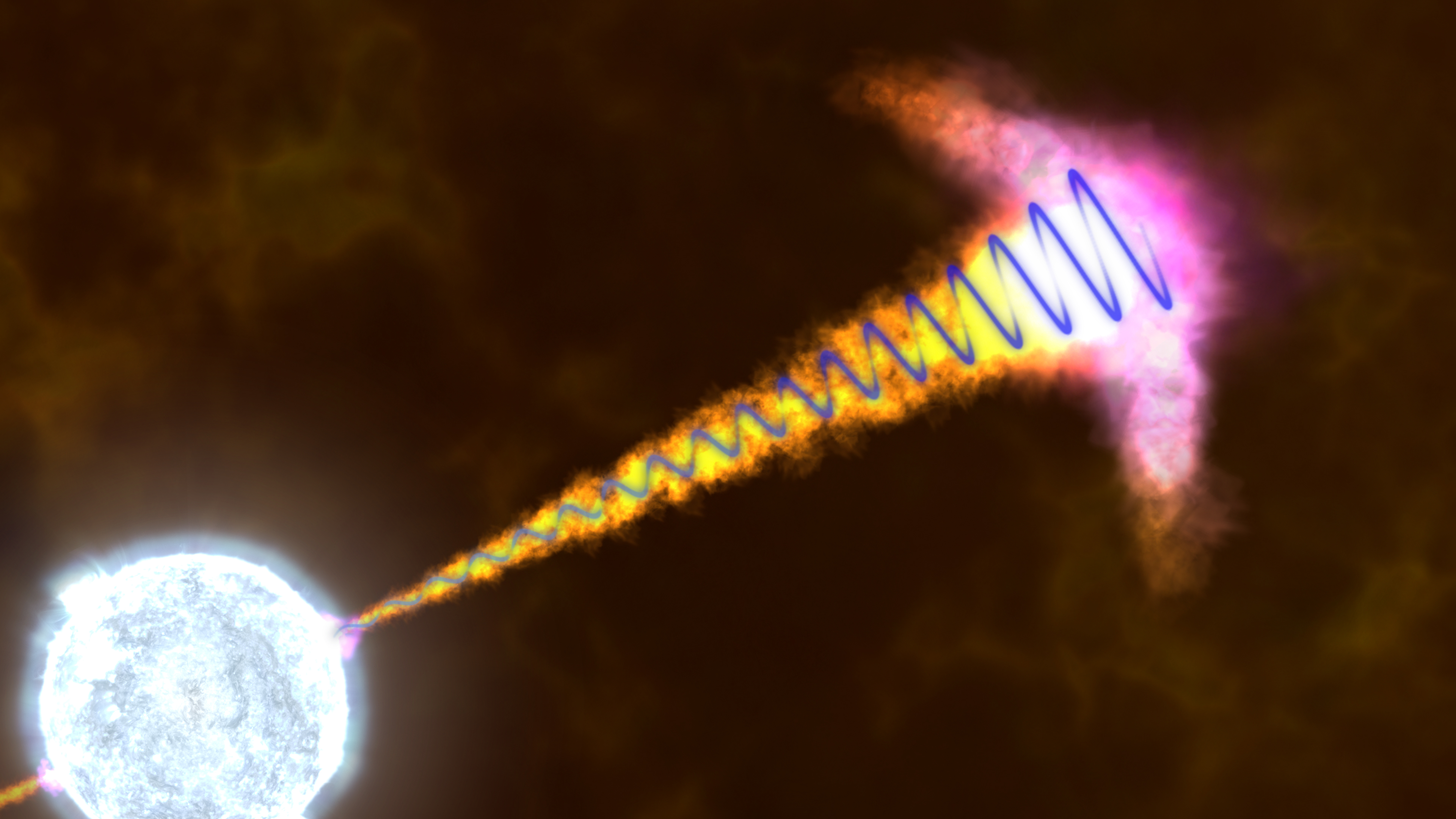

Gamma-ray bursts are believed to form at the end of a massive star's life, just as the body of the star collapses in on itself, creating a black hole. As this happens, the matter surrounding the black hole may release two jets of gamma-rays and highly energetic particles, in opposite directions away from the black hole. A single gamma-ray burst may radiate more energy in a few minutes than the star radiated in its entire lifetime.

Mysterious origins of cosmic explosions

Scientists still don't understand how the particles surrounding a black hole can generate the intense bursts of light and particles seen in gamma-ray bursts.

One theory suggests that an organized magnetic field will accelerate particles on an invisible track around the black hole, causing them to radiate light (what's known as synchrotron radiation). As the black hole rapidly contracts, so do the particles and the magnetic field, causing the particles to accelerate even faster. The theory suggests that it is this rapid bump in acceleration, combined with energy stored in the particles themselves, that creates two massive jets of gamma-rays and particles.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If the energy in a gamma-ray burst was at least partly due to synchrotron radiation, then scientists could expect to see an imprint of that magnetic field in the light produced by this violent event.

New telescope tool's magnetic find

Mundell and her colleagues designed an instrument named RINGO2 to measure the polarization of optical light that is produced as a byproduct of a gamma-ray burst. RINGO2 observed gamma-ray bursts for two years on the Liverpool optical telescope.

On March 8, 2012, NASA's Swift satellite — which tracks gamma-ray bursts — alerted the Liverpool telescope to a cosmic explosion dubbed GRB 120308A. The subsequent study, which was detailed in the Dec. 5 edition of the journal Nature, found that optical light emitted early on by GRB 120308A was 28 percent polarized, and decreased to 10 percent polarization over time.

"If you take optical light and you scatter it from dust, as it comes through our Milky Way galaxy, you might observe a few percent polarization," Mundell said. "Really the only way to produce this high degree of polarization is to have large-scale ordered magnetic fields that are producing the synchrotron radiation with the electrons spiraling around the magnetic field."

Mundell said the reduction in the polarization of the light over time demonstrates that the light is polarized upon its creation near the black hole, and loses its polarization as it travels through space. For this reason, RINGO2 must observe the optical light almost immediately after the start of the gamma-ray burst, in order to observe the polarity.

More observations of polarized light in future gamma-ray bursts are needed to confirm the findings, the researchers said. RINGO2 operated on the Livermore telescope for two years and collected data on multiple gamma-ray bursts.

"We're in the process of working on a sample paper about those other gamma-ray bursts," Mundell said. "Obviously, we want to look at more of them and really prove that this is a universal case and not just a special object. [GRB 120308A] wasn't special in any other way, and that's one good reason to suggest that it was typical."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter