Jupiter Moon Europa May Have Water Geysers Taller Than Everest

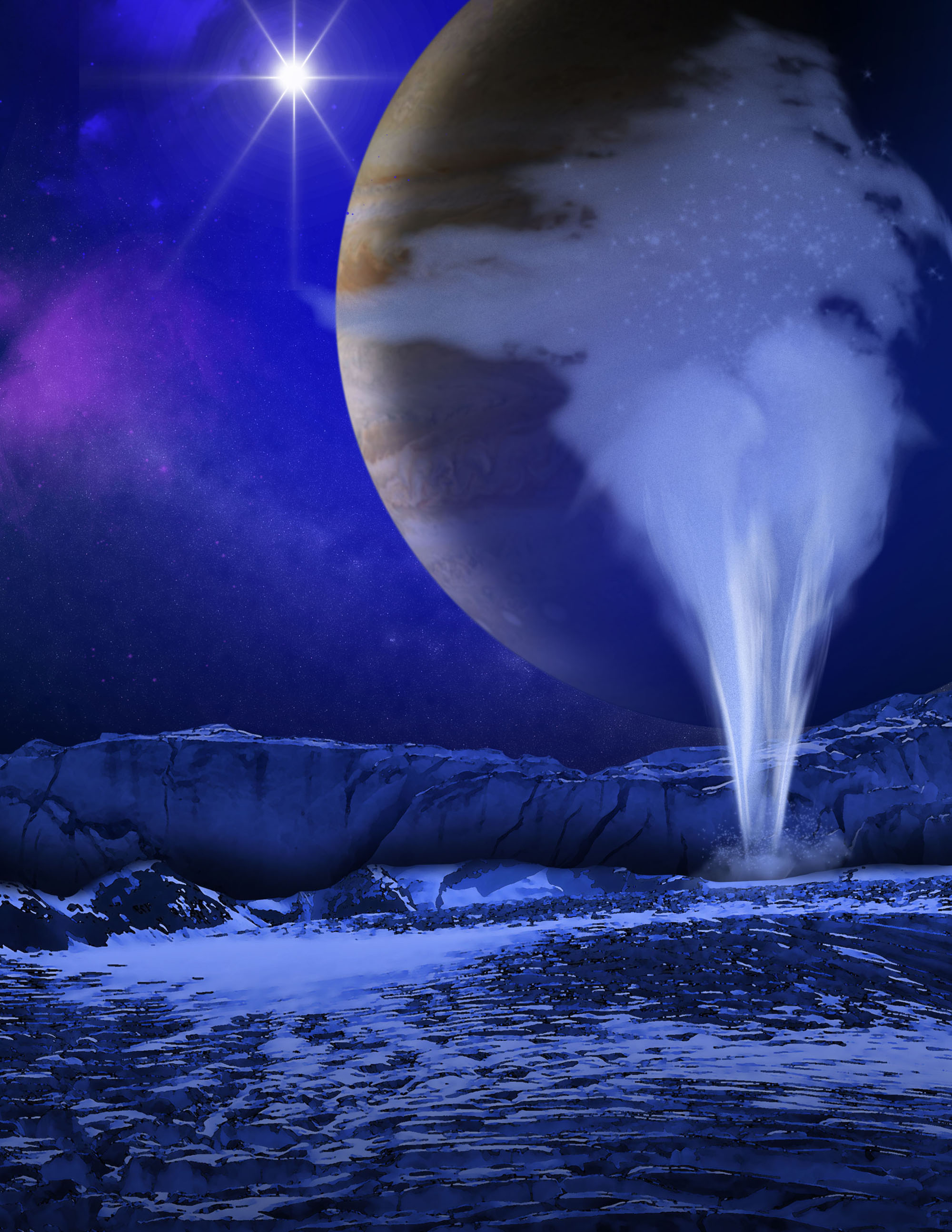

Jupiter's icy moon Europa may erupt with fleeting plumes of water more than 20 times the height of Mt. Everest, scientists say.

If these giant waterspouts are confirmed, they could be a way to detect signs of any life that might exist in the underground ocean that researchers suspect Europa has, scientists added. They were spotted by comparing recent and older images of Europa taken by the Hubble Space Telescope.

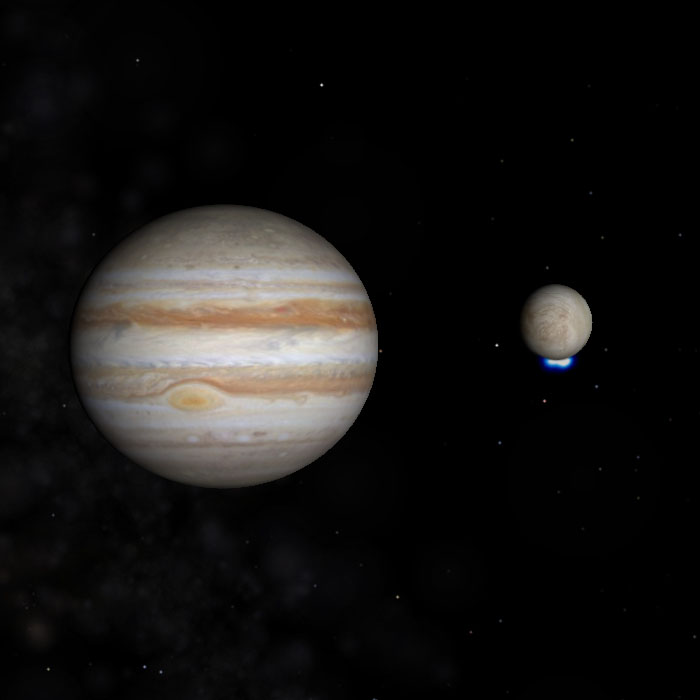

Europa is about the size of Earth's moon. Beneath an icy crust maybe 10 to 15 miles (15 to 25 kilometers) thick, investigators think Europa possesses a giant, churning ocean perhaps up to 100 miles (160 km) deep. Since there is life virtually wherever there is water on Earth, researchers have long wondered if Europa could support life. [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

"A subsurface ocean at Europa potentially provides all conditions for microbial life — at least life we know," study lead author Lorenz Roth, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, told SPACE.com.

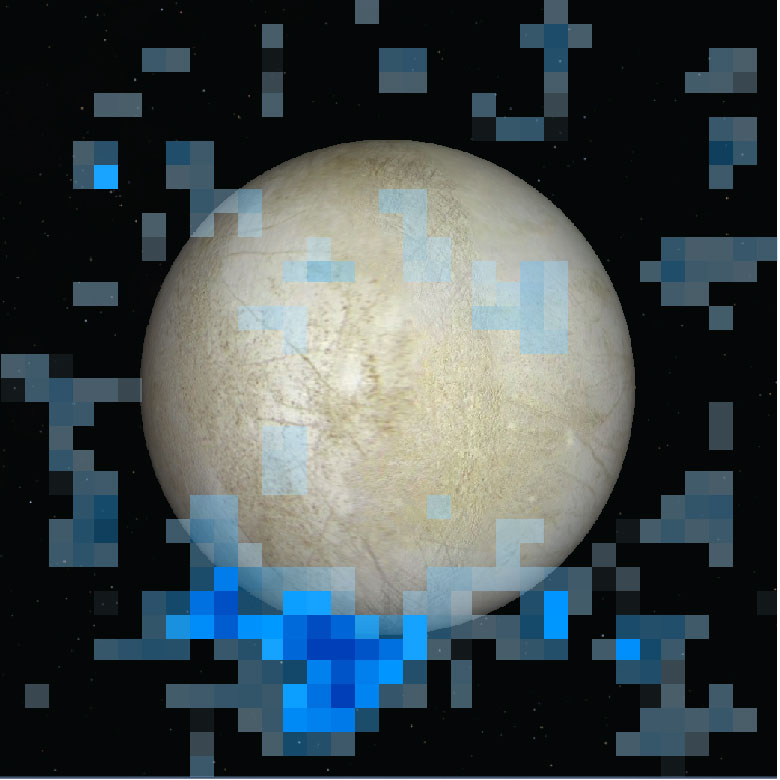

To learn more about the Jovian moon, scientists analyzed ultraviolet images of Europa taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in November and December of 2012 as well as older images taken by Hubble in 1999. They concentrated on finding hydrogen and oxygen, the elements that make up water.

The research was unveiled today (Dec. 12) in the journal Science and is being presented at the annual American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers discovered spikes in hydrogen and oxygen levels in two regions in Europa's southern hemisphere. Computer models suggest these anomalies may be plumes of water vapor 125 miles (200 km) high. These surges were relatively brief, only seen for about seven hours at a time.

These plumes apparently spout when Europa is nearly at its apocenter, or farthest point from Jupiter, and are not seen when Europa is almost at its pericenter, or closest point to Jupiter. This suggests Jupiter's gravity may cause these explosions — the gravitational pull Europa experiences from Jupiter can lead to tidal forces about 1,000 times stronger than what Earth feels from our moon.

It remains uncertain why these plumes happen when Europa is farthest away from Jupiter, when the gravitational pull it experiences from the planet is relatively weak. Perhaps the moon's cracks pull open when Jupiter's pull relaxes on Europa, letting water vapor rush out.

The researchers suggest Europa's plumes appear similar to geysers on Saturn's moon Enceladus, which seem to erupt strongest when the moon is farthest from its planet.

"Europa is half as far away as Enceladus, so Earth-based observations of Europa's plumes will provide higher resolution and sensitivity than possible for Enceladus," Roth said.

Future observations will hopefully confirm this discovery and help define the size, density, composition and timing of Europa's plumes, Roth said. Analyzing the composition of these plumes will allow researchers to scan the makeup of the moon's interior "without landing on Europa and drilling into the ground," Roth said.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us