Megafloods May Have Carved Canyons on Earth & Mars

Nearly 50,000 years ago, a megaflood may have washed across the area that is now Idaho, carving a gorge — a discovery that could explain similar canyons on Mars, a new study finds.

Canyons are ravines typically created by rivers slicing into rock over eons. The shapes of canyons are clues to how water has flowed in the past — not just on Earth, but also on Mars.

"Landforms on Earth and Mars record information about past environments and events that predate the historical record," said study lead author Michael Lamb, a geologist at the California Institute of Technology. "As geologists, we are always seeking new insight to read this record to better understand our planet and its potential for change."

Huge flood

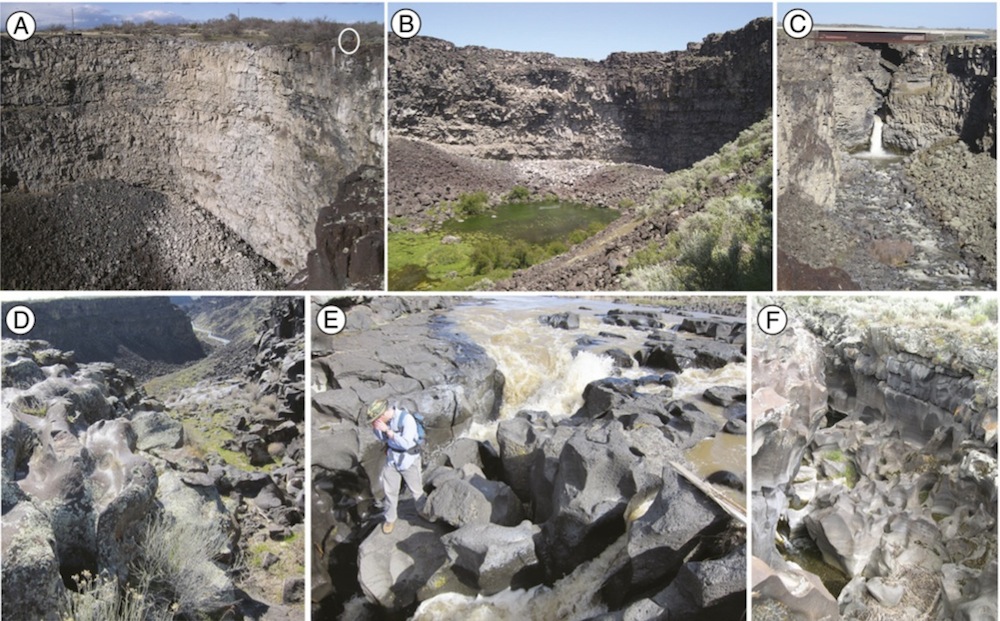

The heads of canyons — the parts of gorges created by the downstream waters of a river — can have a variety of shapes. At times, canyon heads can resemble amphitheaters — the heads are curved when seen from above (think Niagara Falls), and the walls of the canyon heads rise straight up vertically.

"Amphitheater-headed canyons are relatively rare on Earth, but they abound on the surface of Mars," Lamb told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet. [7 Most Mars-Like Places on Earth]

Scientists had suggested amphitheater-headed canyons on Mars were formed by a slow and steady process of erosion from upwelling springs. To find out more about their origins, Lamb and his colleagues examined Malad Gorge in Idaho, a network of ravines cut into volcanic basaltic rock with three heads: Woody's Cove, Stubby Canyon and Pointed Canyon. Both Woody's Cove and Stubby Canyon possess amphitheater heads with vertical walls rising straight up about 165 feet (50 meters) high. In contrast, Pointed Canyon has — as its name suggests — a pointed head, and its walls are stepped in shape.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers estimated the ages of the canyons by analyzing isotopes of elements (atoms with differing numbers of neutrons in their nuclei) in rocks there and examining their physical features, such as canyon rims and scoured rock. Unexpectedly, the researchers discovered the amphitheater-headed canyons of Malad Gorge formed at the same time as the amphitheater-headed Box Canyon, about 11 miles (18 kilometers) to the south — about 46,000 years ago.

These findings, detailed online Dec. 16 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest these amphitheater-headed canyons were formed by the same flood, "and that this flood must have been truly extraordinary in scale," Lamb said. The research team calculated that the flood was at least 30 feet (9 m) deep, flowing at a rate of at least 330,000 gallons per second (1.25 million liters per second).

"The shape of canyon heads may bear important information about the occurrence of extraordinary floods," Lamb said.

'Exciting time to be a geologist'

A brief, powerful flood could have created these amphitheater-headed canyons by exploiting fractures in the rock, "resulting in very rapid erosion," Lamb said. In contrast, Pointed Canyon apparently formed progressively by river erosion over tens of thousands of years.

The amphitheater-headed canyons originated around the same time as the volcanic eruption that led to the creation of the nearby McKinney Butte Basalt. This suggests the catastrophic megaflood that formed them was triggered by lava flows diverting an ancient river.

These insights into ancient megafloods on Earth could, in turn, tells scientists what may have occurred on the surface of Mars millions of years ago.

"Mars has the largest volcanoes in the solar system, and basalt — a volcanic rock — likely covers much of the surface of Mars, implying that many amphitheater-headed canyons on Mars may also owe their origin to large-scale floods," Lamb said.

But Lamb cautioned that amphitheater-headed canyons in rock other than basalt could have different origins.

"For example, amphitheater-headed canyons in loose sand seem to be tied to the slow process of groundwater seepage erosion," Lamb said. "In layered sedimentary rocks with a strong cap rock, long-lived river flows can carve amphitheater-headed canyons like Niagara Falls without the need for extraordinary floods."

The researchers are now developing models simulating canyon formation by megafloods. "We intend to test the model against our data at Malad Gorge and to apply it to specific examples on Mars," Lamb said. "Using Earth as our guide, the early history of Mars surface environments, including the amounts and duration of flowing surface water, is waiting to be discovered through careful analysis of the landforms and sedimentary deposits on the Red Planet. It's an exciting time to be a geologist."

Follow OurAmazingPlanet @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us