Humanoids to 4-Legged Machines: 'Robot Olympics' Shows Off Diverse Designs

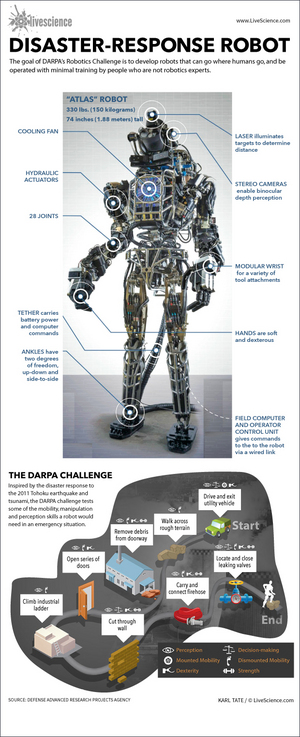

HOMESTEAD, Fla. — This week, teams of engineers from around the world are competing in the DARPA Robotics Challenge Trials, a prestigious robotics competition that will showcase some of the most advanced machines in development. From two-legged creations that resemble humans to bots that drive around on tracks like a tank, the contest boasts a diverse range of robot designs.

The DARPA Robotics Challenge Trials is being held today and tomorrow (Dec. 20-21) here at the Homestead Miami Speedway. The 17 participating teams will be evaluated based on how well their robots tackle eight challenging tasks, which are designed to mimic actions that robots could perform in place of human responders in the wake of natural or man-made disasters.

DARPA, a branch of the U.S. Department of Defense tasked with developing new technologies for the military, hopes the Challenge will foster the development of robots that could one day work in emergency settings deemed too dangerous for humans, said Gill Pratt, program manager of the DARPA Robotics Challenge (DRC). [Watch Live: DARPA Robotics Challenge]

The robots on display in Florida will be various shapes and sizes, with each robotic design having inherent benefits and drawbacks, he added. As such, it can be difficult to predict which type of robot may prevail at the trials.

Different designs, different functions

At this week's Challenge, the majority of competing robots will stand upright on two legs, and were built to resemble human beings. This is largely because DARPA envisions these robots eventually working alongside, and in the same environment, as humans, Pratt said. [Images: DARPA Robotics Challenge]

"If you want a robot to get around and do things in that environment, there's a pull, or engineering desire, to make robots have the same form [as humans]," Pratt told reporters in a news briefing.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Machines that resemble humans, the thinking goes, may operate more seamlessly in a world built around human specifications, such as being able to wield tools designed for human hands. But, there are downsides, said Chris Jones, director of strategic technology development at iRobot Corporation, the Bedford, Mass.-based company behind the well-known robotic Roomba vacuum, which can autonomously clean floors while avoiding obstacles around the house.

"Legged [robots] are interesting, but technically very challenging to accomplish," Jones told LiveScience. "Yes, you can build humanoid robots, and yes, they can fit in the human environment, but can you do it in a cost-effective fashion to justify the inherent complexity?"

iRobot is not competing in the Robotics Challenge, but the company did design a three-fingered robotic hand that will be used by several groups that qualified for the DARPA trials.

Tackling mobility

With a humanoid robot, some of the most challenging issues involve figuring out how it will move around effectively, said Rodney Brooks, founder and CTO of Rethink Robotics, a commercial robotics company based in Boston, Mass. (Rethink is not participating in the DARPA Challenge.) Brooks, who was a professor of robotics at MIT, also co-founded iRobot in 1990, but he is no longer affiliated with the company. [Super-Intelligent Machines: 7 Robotic Futures]

"You have to balance, and that's really hard," Brooks told LiveScience. "There's also a lot of work to be done in figuring out efficient walking algorithms to get good performance."

With four- and six-legged robots, maintaining balance is less precarious. Similarly, robots on tracks are more stable when they move, compared with two-legged machines.

"Tracked vehicles can get over rough terrain without having to worry about where to put a foot down, or how to control the dozen motors required for the walking motion," Jones said. "It's easier that way to keep balance."

Pushing the limits

Right now, human muscles are also simply more agile than their mechanical counterparts. This becomes particularly challenging for larger, humanoid robots, because their mechanical legs have to contend with a greater distribution of mass.

"Building a big thing that walks is harder than building a small thing that walks — things work differently on a micro scale," Brooks said. "It has to do with the strength to weight ratio. This is why an elephant's legs are much weaker, relative to its body mass, compared to an ant."

And then there's a clumsiness of sorts. "Where we are right now, robots are roughly at the same level of dexterity and mobility of a 1-year-old child," Pratt said. "They fall down, they drop things out of their hands all the time — in general, they need to try things many times to get them right. That's about where the field is now."

Yet, DARPA is well aware that the robotics industry has a ways to go before these types of machines live up to the imaginations of Hollywood filmmakers and science-fiction writers, and the agency hopes incentive-based contests like the Robotics Challenge will spur continued growth in the field. But for now at the DARPA trials, the robots that do walk on two legs will likely take slow and deliberate steps, event organizers have said. Even the multi-legged robots, and those that will move on tracks, represent advanced technologies in a fledgling industry.

And, testing a variety of robot designs at the DARPA trials will help engineers better understand which features work best in different disaster scenarios.

"That's part of the point," Brooks said. "You take a bunch of designs and see how far you can push them."

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.