Mock Mars Mission: Utah Habitat Simulates Life on Red Planet

OTTAWA, CANADA — Scientists, engineers and legions of volunteers have worked hard to make a mock Mars habitat in Utah as realistic as possible.

The Mars Desert Research Station (MDRS), which is run by the nonprofit Mars Society, aims to help humanity prepare for the rigors and challenges of life on the Red Planet. It was designed in line with Mars Society founder Robert Zubrin's "Mars Direct" settlement approach, which sees crews living off the land as much as possible, MDRS director Shannon Rupert told SPACE.com.

"The idea was a small crew on these kind of preplanned set of missions that would allow astronauts to get there and have a functioning habitat in place," Rupert said. "We approached it from the idea that it's there and ready to go, and they [the crew] just have to land." [The 9 Coolest Mock Space Missions]

Mars on Earth

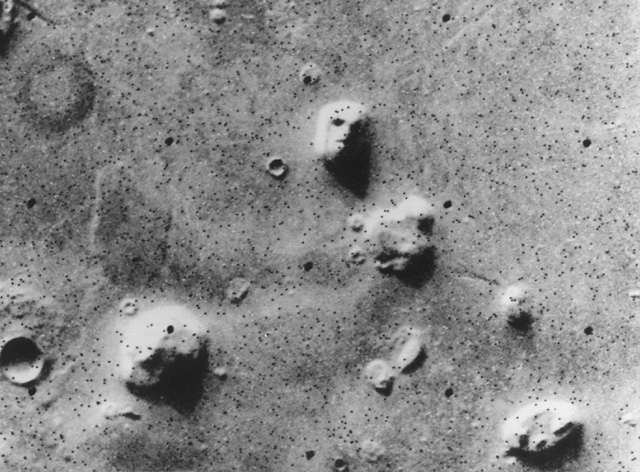

Reading through an unofficial "geology guide" to MDRS (published by past visitors) reveals a dry landscape shaped by wind — a similar environment to many areas of the modern-day Red Planet.

The MRDS habitat near Hanksville, Utah, lies in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, the 2008 guide from MDRS Crews 42 and 71 says. The area only gets about 10 to 20 inches (25 to 50 centimeters) of precipitation of year — some of that rain, and some of it snow.

Colors and landscape blur together to the untrained eye, but a scientist sees a very different picture. For example, layers of material laid down over geologic time are relatively undisturbed, implying that the area doesn't have a lot of tectonic activity. Cracks in the soil, which look somewhat like polygons, were formed mostly because the area is so dry, the guide adds.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While my University of North Dakota-led crew is getting ready to sample the area's geology during our mission, which runs from Jan. 4-19, Mars Society volunteers spent the past few months getting the 1,200-square-foot (111 square meters) habitat ready for residents. This year's research season runs from December to May.

It sure feels like Mars on the outside, past crewmembers say, but the Mars Society also wanted to make the habitat as similar to potential living spaces on the Red Planet as possible.

Unlimited power and scarce water

The habitat is the product of a great deal of analysis over the years, as the Mars Society and its advisors have considered what would be abundant resources on Mars — and which would be scarce ones.

Power, the planners reason, would be easy to get with the help of solar panels. (Right now, two large diesel generators fill that need for the habitat.) Water, however, would be limited, which is why the crew must send daily reports of water usage and keep showers to a military-style, two-minute sprint every other day. Each crew receives two bins of shelf-stable food to eat, and they can even harvest something from a nearby greenhouse (once the plants have grown enough).

While limited Internet connectivity is available to the crew, phone conversations are prohibited because these are not an accurate representation of how Earth-to-Mars communications would proceed. To communicate with the outside world and Mission Control, crew members send updates by e-mail, pictures and more recently, through videos that are all uploaded to the Mars Society website and social media feeds.

Hundreds of volunteer hours

In very rough terms, MDRS costs about $50,000 a year to operate, but that does not take into account the hundreds of volunteer hours that go into preparing the habitat for crews and communicating with them during missions, Rupert said.

There is a mission support crew of 50 to 60 volunteers scattered all over the world. A GreenHab team monitors the greenhouse, a CapCom keeps in contact with the crew, an engineering team helps if something breaks and more teams pitch in for a variety of other needs.

"I think they're awesome," Rupert said of the current teams, although she acknowledged some past seasons were a challenge. MDRS had some "benign neglect" a few years ago due to personnel problems, Rupert said, but she emphasized things are back on track now.

Amid the constant upgrades any aging space habitat needs — a new kitchen was installed four years ago, for example — Rupert also has her eye on improvements in the next couple of years. A tunnel will be built between the observatory and the habitat, and a new greenhouse is likely coming soon.

"Often the focus is on the crews," Rupert said of coverage of MDRS, but she added the unsung heroes are the volunteers who help make those crews as comfortable as possible. "They work all year long on this."

Elizabeth Howell will embark on a two-week simulation at the Mars Desert Research Station operated by the Mars Society from Jan. 4 to 19. Have a burning question about the mission or a picture you really would like to see from the site? E-mail contact@elizabethhowell.ca for the chance to get your question answered in a future story.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.