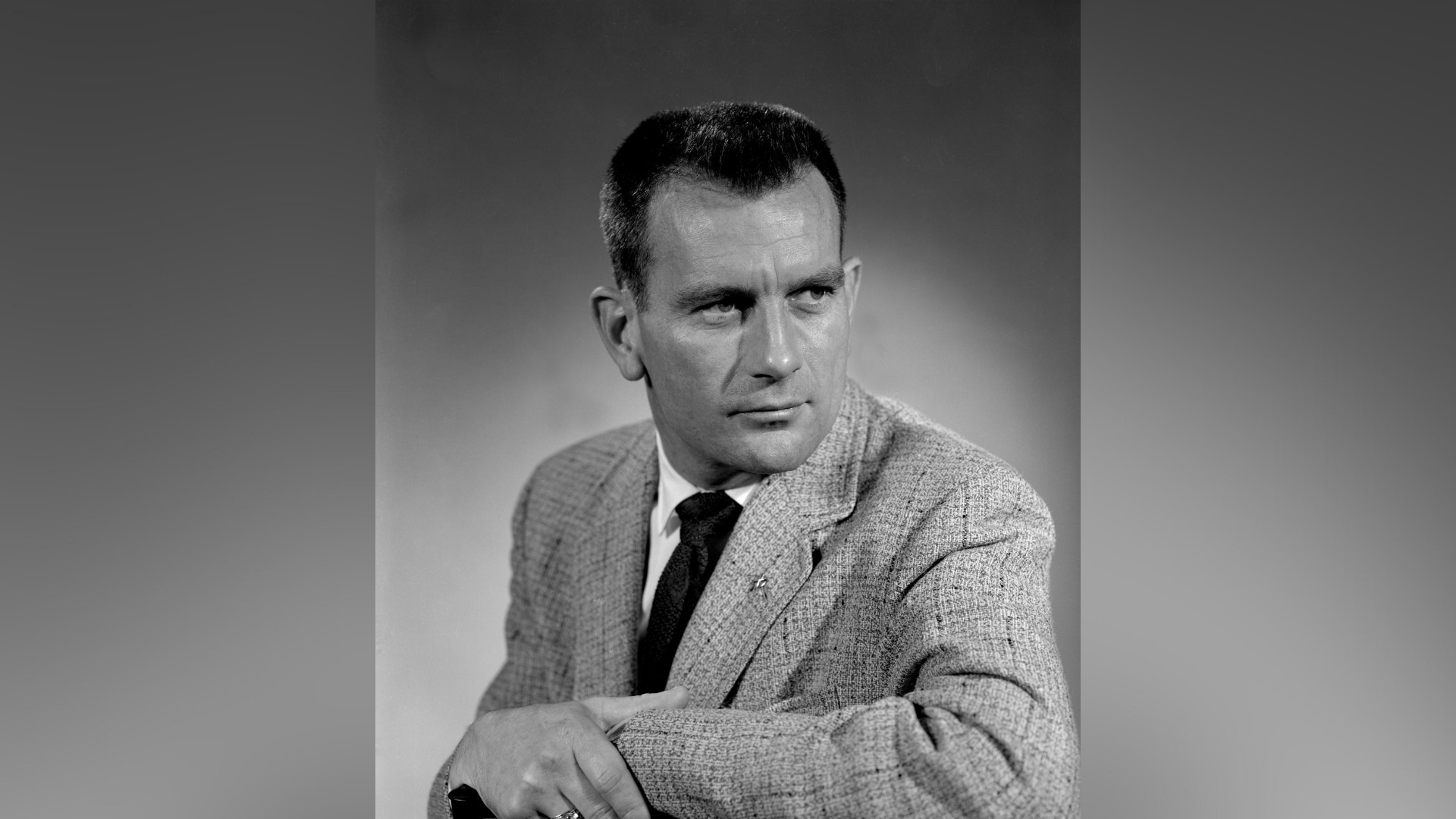

Donald "Deke" Slayton: Mercury astronaut who waited more than a decade to fly to space

Slayton made his first space flight in 1975 as the Apollo docking module pilot of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) mission.

Donald "Deke" Slayton was one of the original Mercury 7 astronauts — but he never flew in that program. Because of a heart condition, he was grounded for decades before being approved and flying in the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the first joint mission with the Soviet Union.

Slayton first got his wings in April 1943 and subsequently undertook dozens of combat flights in Europe and Japan during World War II. He then left the Air Force to study aeronautical engineering, worked at Boeing Aircraft Co. for two years, and then joined the Minnesota Air Guard in 1951, according to NASA.

After undertaking jobs such as maintenance flight test officer of an F-51 squadron, Slayton took classes at the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California and then became a test pilot there before being selected in 1959 for the NASA astronaut program.

Mercury selection

The selection of Slayton and his fellow six astronauts for Mercury gained worldwide attention. At the time, the United States was engaged in what became known as a "Space Race" with the Soviet Union; the two superpowers were using space as a frontier to demonstrate their technical prowess. The fight was on to send a man into space first, and then (eventually) to aim for the moon.

Mercury was the program the United States used to prove that humans could function effectively in zero gravity. Slayton was assigned to the first orbital flight, but was reassigned after NASA changed the schedule to make the third Mercury flight (piloted by John Glenn) an orbital flight rather than a suborbital one.

While Slayton was in training for this second orbital mission, NASA pulled him from flight status in March 1962 over concern about his variable heart rate (or idiopathic atrial fibrillation) that was first discovered three years before.

Slayton was upset. He in part blamed Dr. Larry Lamb (an Air Force flight surgeon who also was cardiologist for President Lyndon Johnson) for raising "hell at a pretty high level" in 1961, which prompted an investigation. The fibrillation also drew concern from then-NASA administrator Jim Webb that it would "cause newspaper headlines," Slayton said in his memoir, "Deke!" "[Lamb] felt quite strongly that this heart fibrillation should disqualify me from flight. He hadn't said so in 1959, but he said so now," he added.

Heading the Astronaut Office

Scott Carpenter took over Slayton's flight, and Slayton was reassigned to other duties within NASA. He became the assistant director of flight crew operations of the new Astronaut Office in 1962 and in 1966, was director of flight crew operations. These roles meant that he had a "key role" in selecting astronaut crews, according to a NASA biography.

Slayton set up a rotation system where astronauts would, generally speaking, become prime crewmembers two flights after serving as a backup crew. He felt this was a fair system, according to "Apollo: The Race to the Moon," and at least some astronauts spoke with respect about his careful selection. "More than a boss, he became the trusted 'Godfather' to the corps of astronauts, respected by all, including NASA senior management," wrote Apollo 17 astronaut Eugene Cernan in his biography, "The Last Man on the Moon."

Dreams of flying in space hadn't left Slayton, however, as he did what he could to try to get his heart back in shape, including exercise, ceasing smoking and taking vitamins. When Slayton finally got flight status again in March 1972, he celebrated by taking a T-38 trainer out of Ellington Air Force Base in Texas and flying aerobatic maneuvers for an hour, NASA said.

Apollo-Soyuz

Slayton was then assigned to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, which was a single mission designed to have the United States and the Soviet Union working closely together in space. NASA astronauts Slayton, Thomas Stafford and Vance Brand did two years of training between 1973 and 1975, while the Russians got Aleksey Leonov and Valeriy Kubasov ready.

Besides learning how to work their spacecraft, the astronauts and cosmonauts learned each other's languages. "When I added up the hours later, I found I spent more time studying Russian than doing any other kind of training for Apollo-Soyuz," Slayton wrote in "Deke!" The Apollo crew launched into space on July 15, 1975, and spent nine days there, docking with the Russian Soyuz spacecraft for 44 hours and performing joint diplomatic and scientific operations.

After Apollo-Soyuz, Slayton shifted his attention to the upcoming shuttle program. He was the manager for the Enterprise shuttle prototype approach and landing tests, which concluded in late 1977. He then managed NASA's orbital flight training program before retiring in February 1982, about one year after the shuttle started flying in April 1981.

After retirement from NASA, Slayton held roles with Space Systems Inc., International Formula One Pylon Air Racing and Columbia Astronautics, among other organizations. Slayton died of brain cancer in 1993.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.

- Elizabeth HowellFormer Staff Writer, Spaceflight (July 2022-November 2024)