How long does it take to get to Mars?

We explore how long it takes to get to Mars and the factors that affect a journey to the Red Planet.

Have you ever wondered what it takes to journey to Mars?

A one-way trip to the Red Planet would take nine months but a return journey would be around three years.

While these estimates provide a general idea, the actual duration is influenced by several factors. The distance between Earth and Mars changes constantly due to their orbits, and the technology used to propel spacecraft plays a significant role in determining travel time. In this article, we delve into the mechanics of traveling to Mars using current technology and examine the variables that impact the length of the journey.

How far away is Mars?

To determine how long it will take to reach Mars, we must first know the distance between the two planets.

Mars is the fourth planet from the sun, and the second closest to Earth (Venus is the closest). But the distance between Earth and Mars is constantly changing as they orbit the sun.

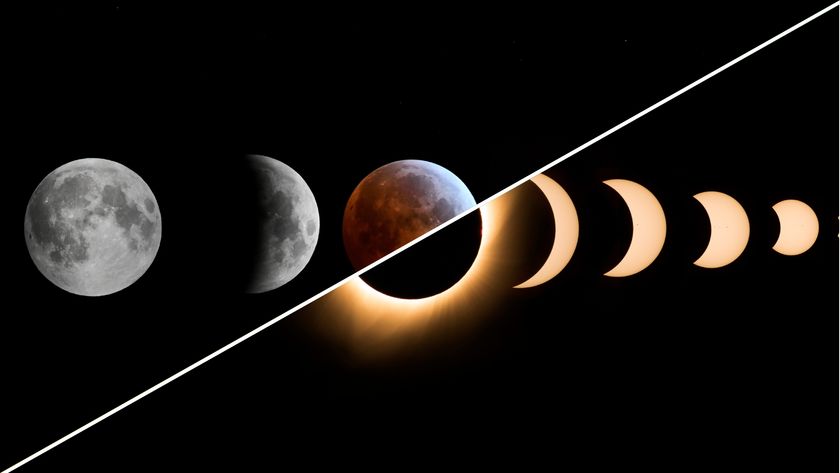

In theory, the closest that Earth and Mars would approach each other would be when Mars is at its closest point to the sun (perihelion) and Earth is at its farthest (aphelion). This would put the planets only 33.9 million miles (54.6 million kilometers) apart. However, this has never happened in recorded history. The closest recorded approach of the two planets occurred in 2003 when they were only 34.8 million miles (56 million km) apart.

The two planets are farthest apart when they are both at their farthest from the sun, on opposite sides of the star. At this point, they can be 250 million miles (401 million km) apart.

The average distance between Earth and Mars is 140 million miles (225 million km).

Related: What is the temperature on Mars?

How long would it take to travel to Mars at the speed of light?

Light travels at approximately 186,282 miles per second (299,792 km per second). Therefore, a light shining from the surface of Mars would take the following amount of time to reach Earth (or vice versa):

- Closest possible approach: 182 seconds, or 3.03 minutes

- Closest recorded approach: 187 seconds, or 3.11 minutes

- Farthest approach: 1,342 seconds, or 22.4 minutes

- On average: 751 seconds, or just over 12.5 minutes

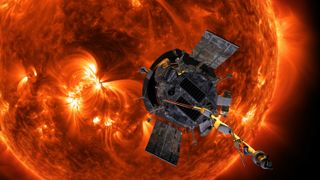

Fastest spacecraft so far

The fastest spacecraft is NASA's Parker Solar Probe, as it keeps breaking its own speed records. On Dec. 24, 2024, the Parker Solar Probe reached a top speed of 430,000 miles per hour (692,000 km per hour).

So if you were theoretically able to hitch a ride on the Parker Solar Probe and take it on a detour from its sun-focused mission to travel in a straight line from Earth to Mars, traveling at the speeds the probe reaches during its 22nd solar flyby 430,000 mph (692,000 kph), the time it would take you to get to Mars would be:

- Closest possible approach: 78.84 hours (3.3 days)

- Closest recorded approach: 80.93 hours (3.4 days)

- Farthest approach: 581.4 hours (24.2 days)

- On average: 325.58 hours (13.6 days)

Mars travel time Q&A with an expert

We asked Michael Khan, ESA Senior Mission Analyst some frequently asked questions about travel times to Mars.

Michael Khan is a Senior Mission Analyst for the European Space Agency (ESA). His work involves studying the orbital mechanics for journeys to planetary bodies including Mars.

How long does it take to get to Mars & what affects the travel time?

The time it takes to get from one celestial body to another depends largely on the energy that one is willing to expend. Here "energy" refers to the effort put in by the launch vehicle and the sum of the maneuvers of the rocket motors aboard the spacecraft, and the amount of propellant that is used. In space travel, everything boils down to energy. Spaceflight is the clever management of energy.

Some common solutions for transfers to the moon are 1) the Hohmann-like transfer and 2) the Free Return Transfer. The Hohmann Transfer is often referred to as the one that requires the lowest energy, but that is true only if you want the transfer to last only a few days and, in addition, if some constraints on the launch apply. Things get very complicated from there on, so I won't go into details.

Concerning transfers to Mars, these are by necessity interplanetary transfers, i.e., orbits that have the sun as central body. Otherwise, much of what was said above applies: the issue remains the expense of energy. An additional complication lies in the fact that the Mars orbit is quite eccentric and also its orbit plane is inclined with respect to that of the Earth. And of course, Mars requires longer to orbit the sun than the Earth does. All of this is taken into account in a common type of diagram called the "pork chop plot", which essentially tells you the required dates of departure and arrival and the amount of energy required.

The "pork chop plot" shows the trajectory expert that opportunities for Mars transfers arise around every 25-26 months, and that these transfers are subdivided into different classes, one that is a bit faster, with typically around 5-8 months and the other that takes about 7-11 months. There are also transfers that take a lot longer, but I’m not talking about those here. Mostly, but not always, the second, slower one turns out to be more efficient energy-wise. A rule of thumb is that the transfer to Mars takes around as long as the human period of gestation, approximately 9 months. But that really is no more than an approximate value; you still have to do all the math to find out what applies to a specific date.

Why are journey times a lot slower for spacecraft intending to orbit or land on the target body e.g. Mars compared to those that are just going to fly by?

If you want your spacecraft to enter Mars orbit or to land on the surface, you add a lot of constraints to the design problem. For an orbiter, you have to consider the significant amount of propellant required for orbit insertion, while for a lander, you have to design and build a heat shield that can withstand the loads of atmospheric entry. Usually, this will mean that the arrival velocity of Mars cannot exceed a certain boundary. Adding this constraint to the trajectory optimisation problem will limit the range of solutions you obtain to transfers that are Hohmann-like. This usually leads to an increase in transfer duration.

The problems with calculating travel times to Mars

The problem with the previous calculations is that they measure the distance between the two planets as a straight line. Traveling through the farthest passing of Earth and Mars would involve a trip directly through the sun, while spacecraft must of necessity move in orbit around the solar system's star.

Although this isn't a problem for the closest approach, when the planets are on the same side of the sun, another problem exists. The numbers also assume that the two planets remain at a constant distance; that is, when a probe is launched from Earth while the two planets are at the closest approach, Mars would remain the same distance away over the length of time it took the probe to travel.

Related: A brief history of Mars missions

In reality, however, the planets are moving at different rates during their orbits around the sun. Engineers must calculate the ideal orbits for sending a spacecraft from Earth to Mars. Like throwing a dart at a moving target from a moving vehicle, they must calculate where the planet will be when the spacecraft arrives, not where it is when it leaves Earth.

It's also not possible to travel as fast as you can possibly go if your aim is to eventually orbit your target planet. Spacecraft need to arrive slow enough to be able to perform orbit insertion maneuvers and not just zip straight past their intended destination.

The travel time to Mars also depends on the technological developments of propulsion systems.

According to NASA Goddard Space Flight Center's website, the ideal lineup for a launch to Mars would get you to the planet in roughly nine months. The website quotes physics professor Craig C. Patten, of the University of California, San Diego:

"It takes the Earth one year to orbit the sun and it takes Mars about 1.9 years (say 2 years for easy calculation) to orbit the sun. The elliptical orbit which carries you from Earth to Mars is longer than Earth's orbit but shorter than Mars' orbit. Accordingly, we can estimate the time it would take to complete this orbit by averaging the lengths of Earth's orbit and Mars' orbit. Therefore, it would take about one and a half years to complete the elliptical orbit.

"In the nine months it takes to get to Mars, Mars moves a considerable distance around in its orbit, about three-eighths of the way around the sun. You have to plan to make sure that by the time you reach the distance of Mars' orbit, Mars is where you need it to be! Practically, this means that you can only begin your trip when Earth and Mars are properly lined up. This only happens every 26 months. That is, there is only one launch window every 26 months."

The trip could be shortened by burning more fuel — a process not ideal with today's technology, Patten said.

Evolving technology can help to shorten the flight. NASA's Space Launch System (SLS) will be the new workhorse for carrying upcoming missions, and potentially humans, to the red planet. SLS is currently being constructed and tested, with NASA now targeting a launch in March or April 2022 for its Artemis 1 flight, the first flight of its SLS rocket.

Robotic spacecraft could one day make the trip in only three days. Photon propulsion would rely on a powerful laser to accelerate spacecraft to velocities approaching the speed of light. Philip Lubin, a physics professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and his team are working on Directed Energy Propulsion for Interstellar Exploration (DEEP-IN). The method could propel a 220-lb. (100 kilograms) robotic spacecraft to Mars in only three days, he said.

"There are recent advances which take this from science fiction to science reality," Lubin said at the 2015 NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) fall symposium. "There's no known reason why we cannot do this."

How long did previous Mars missions take to reach the Red Planet?

Here is an infographic detailing how long it took several historical missions to reach the Red Planet (either orbiting or landing on the surface). Their launch dates are included for perspective.

Additional resources

Explore NASA's lunar exploration plans with their Moon to Mars overview. You can read about how to get people from Earth to Mars and safely back again with this informative article on The Conversation. Curious about the human health risks of a mission to the Red Planet? You may find this research paper of particular interest.

Bibliography

- Lubin, Philip. "A roadmap to interstellar flight." arXiv preprint arXiv:1604.01356 (2016).

- Donahue, Ben B. "Future Missions for the NASA Space Launch System." AIAA Propulsion and Energy 2021 Forum. 2021.

- Srinivas, Susheela. "Hop, Skip and Jump—The Moon to Mars Mission." (2019).

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!

- Nola Taylor TillmanContributing Writer