High-Res Satellites Help Track Whale Populations

New high-resolution satellite imagery now allows researchers to spot and count whales from space, greatly expediting population analyses used in conservation efforts, according to a new report.

Traditionally, researchers have counted whales from the bows of ships by searching for blowhole sprays and tail flips, but that method is inherently flawed because it relies on chance encounters and because the field of view is often limited to several miles at a time, even on a clear day.

"If you are very skilled, you can judge how far away it is and work out the species from the size and shape of the blow," said Peter Fretwell, a researcher for the British Antarctic Survey. "But it's very difficult, and you have to look in the right place at the right time."

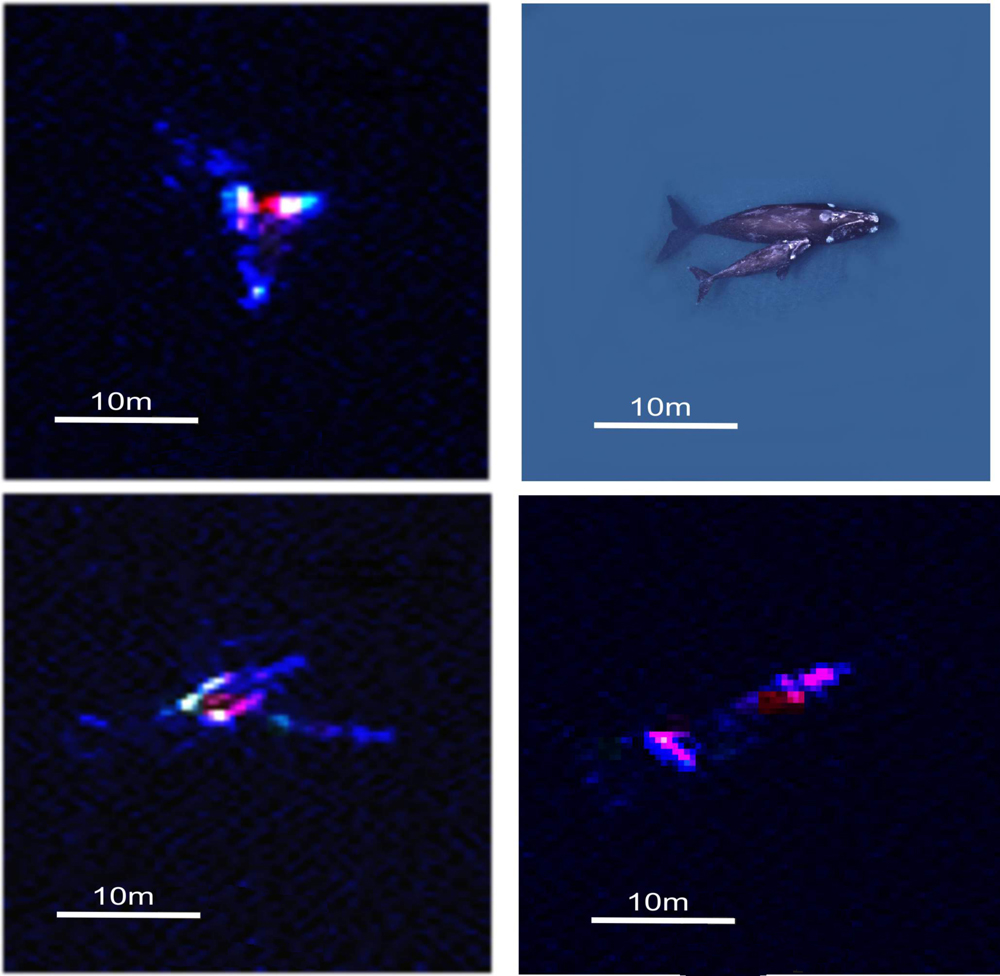

To make whale counts more accurate and efficient, Fretwell's team used what is known as very-high-resolution (VHR) satellite imagery to count a group of southern right whales breeding halfway up the coast of Argentina. The team chose to analyze southern right whales — a large species that grows to be roughly 45 to 55 feet (14 to 17 meters) long and travels around southern regions of the Pacific and Antarctic oceans — during this proof-of-concept study because the species tends to bask at the surface and breed in calm waters, making these whales relatively easy to spot from above. [Whale Album: Giants of the Deep]

The image that the team analyzed had a resolution of 4 pixels per 11 square feet (1 square meter), covered an area of 44 square miles (113 square kilometers) and picked up on a broad spectrum of colors, including dark blues found as deep as 50 feet (15 m) below the surface of the ocean.

The team first manually identified whales from the image and found 55 probable whales, 23 possible whales and 13 other underwater objects that were not whales, such as rocks. They then tested a series of automated image-processing systems, the best of which located 89 percent of the probable whales that they had counted manually, the team reports today (Feb. 12) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Similar techniques have been used to count other marine-animal populations, such as emperor penguins in Antarctica, but this is the first time that researchers have successfully used satellite imagery to count whales, the team said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers hope that this new tool will provide more reliable population counts for groups involved in whale conservation.

Hundreds of thousands of whales once swam the world's oceans, making them one of the most prevalent marine predators. But whaling during the last several centuries devastated many whale populations, leaving several species near extinction. Southern right whales, for example, once totaled nearly 70,000 individuals, but shrank down to only about 300 by the 1920s, Fretwell said. Their numbers have risen in recent decades to several thousand individuals, due largely to the International Whaling Commission's world moratorium on whaling that went into effect in 1986, but this is still only a small fraction of their prewhaling population, Fretwell told Live Science.

The satellite technology and automated image-processing software used in the study work best in calm waters, but Fretwell expects the technology to advance in the future to yield useful results in choppier ocean conditions. This year, a new satellite is scheduled to launch that will produce images with 9 pixels (opposed to 4 pixels) per 11 square feet, which will further improve the accuracy of whale counts from space, Fretwell said.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Residing in Portland, Maine Laura is a seasoned science and environmental journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Smithsonian, Scientific American, Wired, Audubon, National Geographic, Science, and on Space.com and Live Science. Her work at Live Science focused on earth and environmental news. She has a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a Bachelor of Science degree in geology from Bates College in Lewiston, Maine. Laura has a good eye for finding fossils in unlikely places, will pull over to examine sedimentary layers in highway roadcuts, and has gone swimming in the Arctic Ocean.