NASA Mars Probe Shifts Orbit to Study Early-Morning Fogs and Frosts

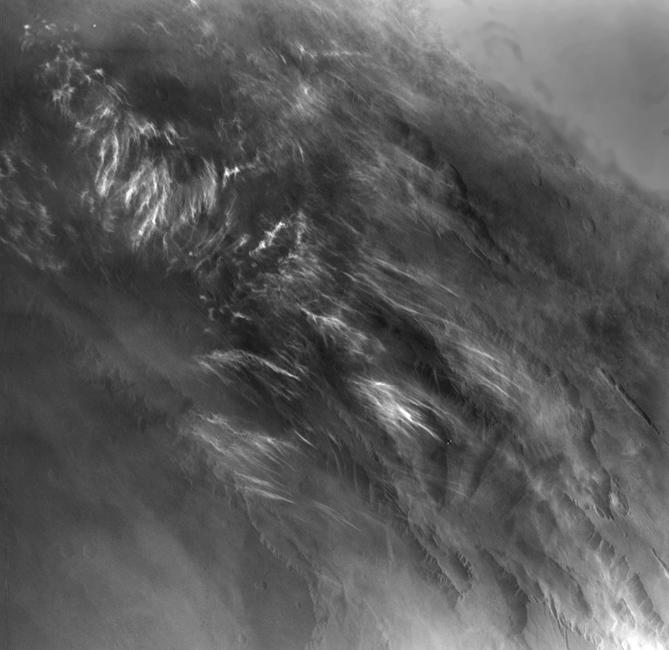

The longest-working Martian spacecraft recently made a slight change to its orbit that will allow it to make the first systematic observations of morning fog, clouds, and surface frost on the Red Planet.

On Feb. 11, NASA's Odyssey orbiter — which arrived at the Red Planet in 2001 — underwent a gentle acceleration to put it into the first sunrise and sunset orbit in almost 40 years.

"We're teaching an old spacecraft new tricks," Odyssey project scientist Jeffrey Plaut, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. "Odyssey will be in a position to see Mars in a different light than ever before." [See photos from NASA's Mars Odyssey mission]

Morning fog and frost

From its new position, Odyssey will make the first sunrise and sunset observations since Voyager visited the planet in the 1970s. Looping the planet several times a day from the north to south pole, and then again from the south to north, the orbiter will follow the dawn and dusk regions around the planet.

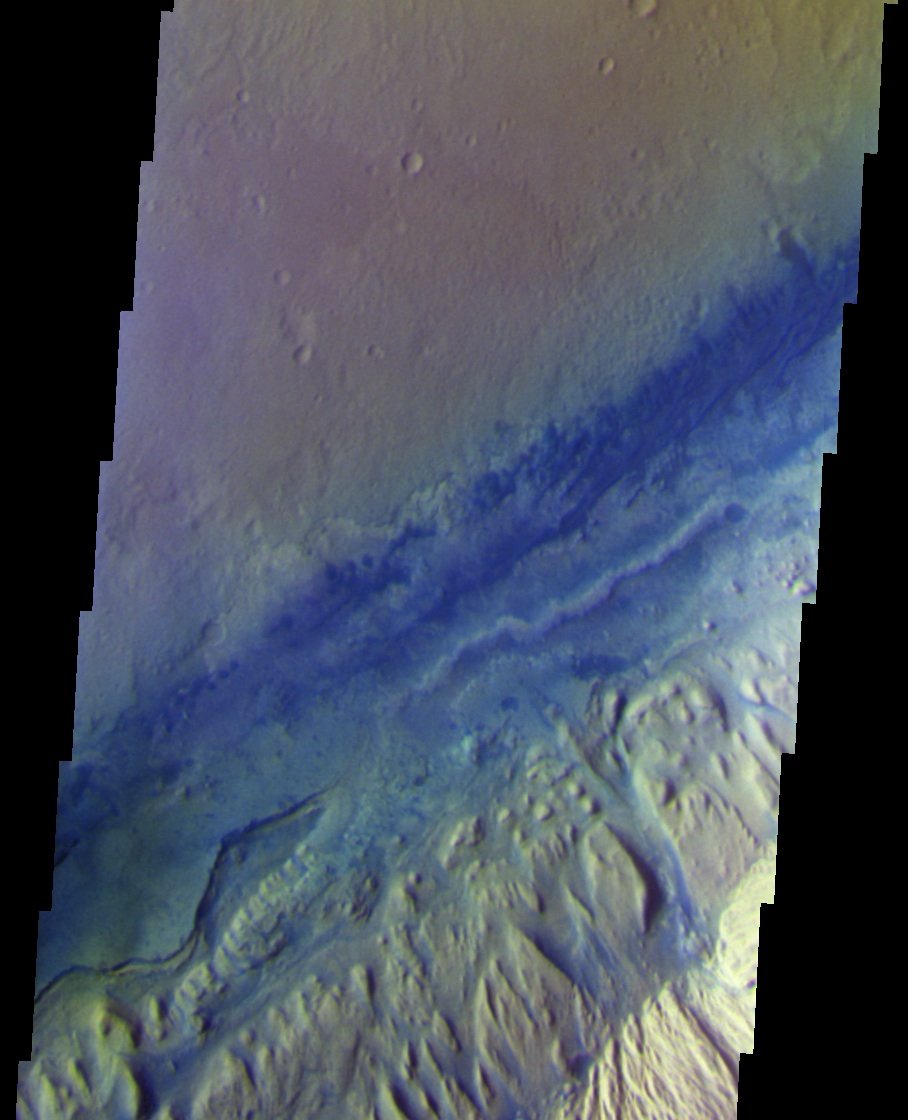

The new orbit will allow the craft to observe the changing ground temperatures just after the sun rises and sets, potentially yielding insight about ground composition. The orbiter's Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) will explore frosts, early-morning clouds and hazes, ground fogs, and other atmosphere-related features that vanish over the course of the Martian day.

"We don't know exactly what we'll find when we get to an orbit where we see Mars just after sunrise," Philip Christensen of Arizona State University said in a statement. Christensen is the designer and principal investigator for THEMIS. "We know that in places, carbon dioxide frost forms overnight. And then it sublimates immediately after sunrise. What would this process look like in action? How would it behave? We've never observed this kind of phenomenon directly."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The long-running mission will allow observations of changing atmospheric features over time, providing greater insights on the Red Planet it and its atmosphere.

"We can look for seasonal differences," Christensen said. "Are fogs more common in winter or spring? Do they vary from day to day? From one part of the year to another? From year to year? We'll check it out."

Scientists also hope to see clues about temperature-driven processes, such as warm-season flows and geysers fed by spring thawing of carbon-dioxide ice.

The times they are a-changin'

Odyssey spent most of its first six years since its 2001 arrival orbiting Mars at about 5 o'clock local solar time. Making a dozen passes each day from the north to the south polar region, the craft observed the Red Planet around 5 a.m., while its south-to-north observations occurred at 5 in the evening. During these passes, the Gamma Ray Spectrometer searched for evidence of water near the Martian surface, and made important discoveries relating to the distribution of water ice on the surface.

The orbiter also spent 3 years at a 4 o'clock orbit, allowing THEMIS to map minerals across the surface. Although the mid-afternoon temperatures made mineral signatures easier to identify, the craft spent more of its orbit in the shadow of the Red Planet, reducing the energy supplied by the solar panels and putting more stress on the orbiter's power system.

In 2012, Odyssey served as a radio-relay support for the landing of NASA's Curiosity rover. Afterward, it began a slow drift to later times of day to preserve the craft's battery.

Christensen suggested letting the orbit shift to just past 6 local time, and making morning observations on the south-to-north half. Four thrusters, burning for 29 seconds on Feb. 11, accelerated the craft toward its final morning orbit, which it should reach after a second burn in November 2015.

Odyssey will continue scientific observations as it gradually shifts its position. The orbiter, which is the longest-running spacecraft ever sent to Mars, should have enough propellant to last another decade based on estimated consumption rates.

"Mars is a dynamic world," Christensen said."And for a generation, we've not been positioned to explore this part of it so thoroughly."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd