Water Found in Atmosphere of Nearby Alien Planet

Water vapor has been detected in the atmosphere of one of the first alien planets ever identified by astronomers.

Advances in the technique used to scan the atmosphere of this "hot Jupiter" could help scientists determine how many of the billions of planets in the Milky Way contain water like Earth, researchers said.

The exoplanet Tau Boötis b was discovered in 1996, when the search for worlds outside our solar system was just kicking off. At about 51 light-years away, Tau Boötis b is one of the nearest known exoplanets to Earth. The planet is considered a "hot Jupiter" because it is a massive gas giant that orbits close to its parent star. [A Gallery of the Strangest Alien Planets]

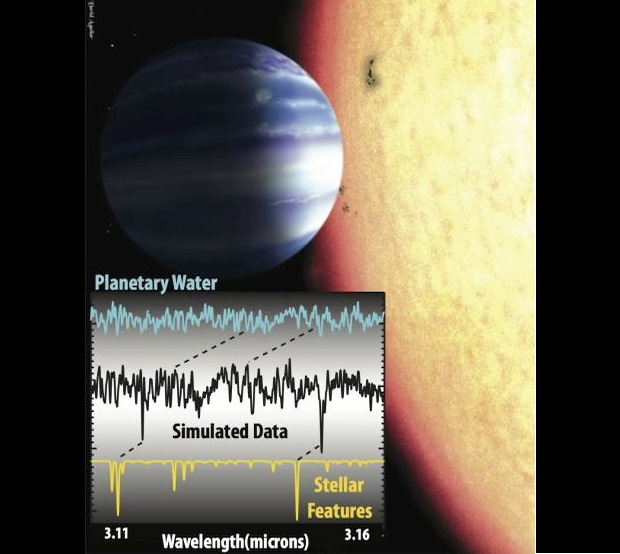

To analyze the atmosphere surrounding Tau Boötis b, scientists looked at its faint glow. Different types of molecules emit different wavelengths of light, resulting in signatures known as spectra that reveal their chemical identify.

"The information we get from the spectrograph is like listening to an orchestra performance; you hear all of the music together, but if you listen carefully, you can pick out a trumpet or a violin or a cello, and you know that those instruments are present," study researcher Alexandra Lockwood, a graduate student at Caltech, explained in a statement.

"With the telescope, you see all of the light together, but the spectrograph allows you to pick out different pieces; like this wavelength of light means that there is sodium, or this one means that there’s water," Lockwood added.

Scientists have used spectrographic analyses to find water signatures on other alien planets before, but only when those worlds passed in front of their parent stars. Tau Boötis b does not transit in front of its parent star from our viewpoint on Earth, but Lockwood and colleagues were able to tease out the weak light emitted by the planet using the Near Infrared Echelle Spectrograph (NIRSPEC) at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Researchers had previously used a similar technique to find carbon monoxide around Tau Boötis b. That compound is thought to be the second-most common gas in the atmospheres of hot Jupiters, after hydrogen.

The new analysis showed that the glow of the planet's atmosphere matches the distinct molecular signature of water, the researchers say.

The spectrographic technique is presently limited to big planets orbiting closely to bright stars, like hot Jupiters, but it could eventually be used to study super-Earths (planets slightly larger than Earth) and worlds in the "habitable zone" around their parent stars, where liquid water and perhaps life as we know it could exist.

"While the current state of the technique cannot detect Earth-like planets around stars like the sun, with Keck it should soon be possible to study the atmospheres of the so-called 'super-Earth' planets being discovered around nearby low-mass stars, many of which do not transit," Caltech professor Geoffrey Blake said in a statement.

"Future telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope and the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) will enable us to examine much cooler planets that are more distant from their host stars and where liquid water is more likely to exist," Blake added.

Astronomers found the first evidence of an exoplanet in 1992. Since then, more than 1,000 worlds have been discovered outside of our solar system, and many more await confirmation.

The new findings were detailed in the Feb. 24 online version of The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The results are also freely available on the preprint service Arxiv.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.