Supermassive black holes could be quenching star formation in elliptical galaxies, forcing them to appear "red and dead," a new study reports.

Astronomers have long wondered why giant elliptical galaxies stop forming stars, becoming dominated over time with small, long-lived stars with a distinctive reddish tinge. Conventional wisdom had held that these galaxies lack the cold gas necessary for star birth.

But new observations suggest that a rethink is in order. Some big ellipticals do indeed harbor large amounts of cold gas — but these reservoirs likely get heated up or driven off by powerful jets of material blasted out by supermassive black holes, which lurk at the heart of most if not all galaxies. [The Strangest Black Holes in Space]

![Black holes are strange regions where gravity is strong enough to bend light, warp space and distort time. [See how black holes work in this SPACE.com infographic.]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/8GbuLi8DVtx8HoZeSyndT7.jpg)

"These galaxies are red, but with the giant black holes pumping in their hearts, they are definitely not dead," study lead author Norbert Werner, of Stanford University, said in a statement.

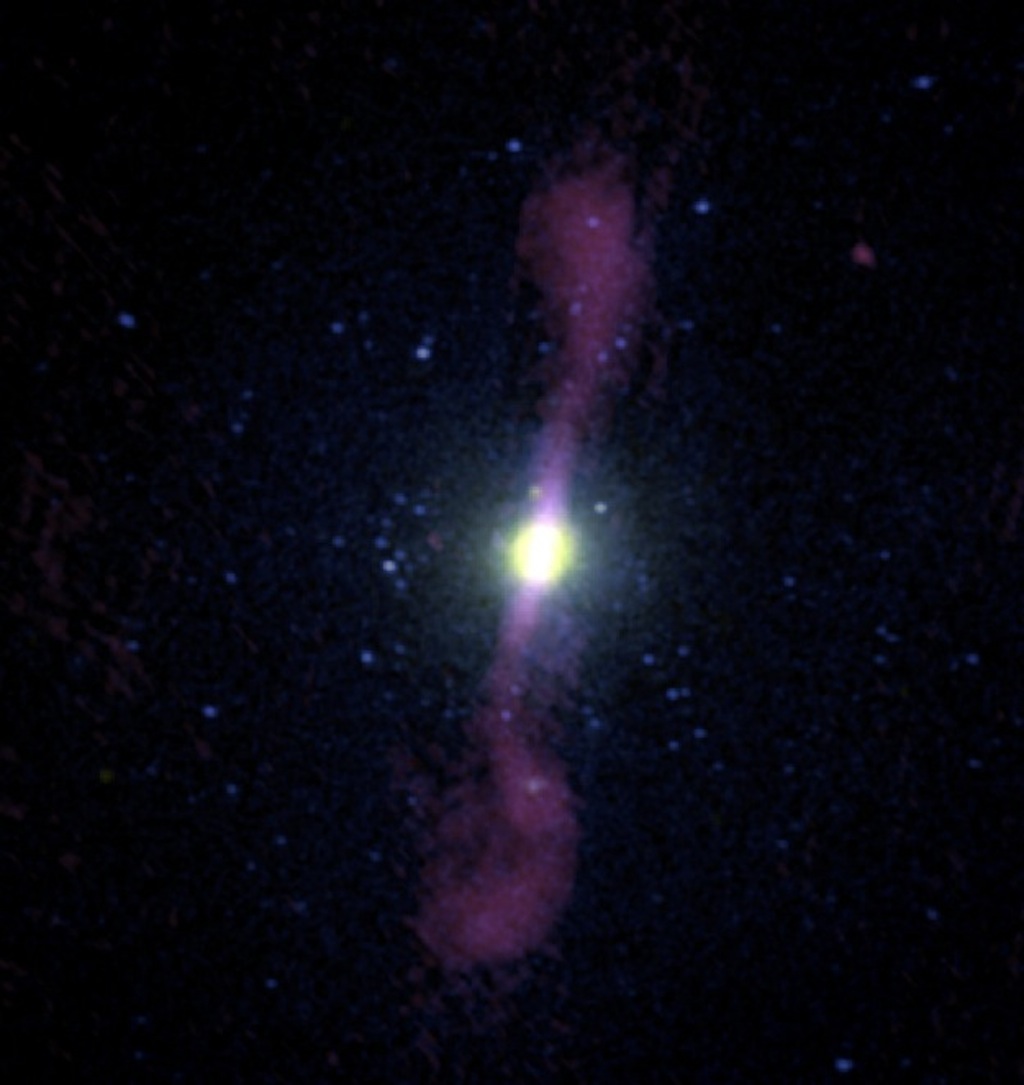

Werner and his colleagues studied eight giant elliptical galaxies using the European Space Agency's Herschel Space Observatory. They found that six of the eight have lots of cold gas, which Herschel detected as far-infrared emissions from carbon ions and oxygen atoms.

The team then investigated the galaxies' stockpiles of hotter gas, looking at optical images as well as X-ray data gathered by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory.

They determined that, in the six galaxies with large quantities of cold gas, the hotter stuff is cooling down, as predicted by theory — but the cooling process has stopped for some reason. In the two galaxies without cold gas, the hot material seems not to be cooling down at all, researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The contrasting behavior of these galaxies may have a common explanation: the central supermassive black hole," said co-author Raymond Oonk of ASTRON, the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy.

The two ellipticals without cold gas have incredibly active central black holes at their cores, which are accreting material at a breakneck pace and launching energetic jets out into space, researchers said. These jets could be reheating the cold gas or clearing it away from the galaxies altogether.

This process may explain why star formation has halted in all eight elliptical galaxies, study team members said.

"Once again, Herschel has detected something that was never seen before: significant amounts of cold gas in nearby red-and-dead galaxies," said Göran Pilbratt, Herschel project scientist at ESA. "Nevertheless, these galaxies do not form stars, and the culprit seems to be the black hole."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.