What is Space?

Space, the final frontier, what is it?

We often refer to our expanding universe with one simple word: space. But where does space begin and, more importantly, what is it?

Space is an almost perfect vacuum, nearly void of matter and with extremely low pressure. In space, sound doesn't carry because there aren't molecules close enough together to transmit sound between them. Not quite empty, bits of gas, dust and other matter floats around "emptier" areas of the universe, while more crowded regions can host planets, stars and galaxies.

From our Earth-bound perspective, outer space is most often thought to begin about 62 miles (100 kilometers) above sea level at what is known as the Kármán line. This is an imaginary boundary at an altitude where there is no appreciable air to breathe or scatter light. Passing this altitude, blue starts to give way to black because oxygen molecules are not in enough abundance to make the sky blue.

Related: Where DOES Space Begin? Virgin Galactic Flies Right into the Debate

No one knows exactly how big space is. It's difficult to determine because of what we can see in our detectors. We measure long distances in space in "light-years," representing the distance it takes for light to travel in a year (roughly 5.8 trillion miles (9.3 trillion kilometers)).

From the light that is visible in our telescopes, we have charted galaxies reaching almost as far back as the Big Bang, which is thought to have started our universe about 13.8 billion years ago. This means we can "see" into space at a distance of almost 13.8 billion light-years. But the universe continues to expand, making "measuring space," even more challenging.

Additionally, astronomers are not totally sure if our universe is the only one that exists. This means that space could be a whole lot bigger than we even think.

Space radiation invisible to human eyes

The majority of space is relatively empty, with just stray bits of dust and gas floating around. This means that when humans send a probe to a distant planet or asteroid, the craft will not encounter "drag" in the same way that an airplane does as it sails through space.

In fact, the vacuum environment in space and on the moon, is one reason why the lunar lander of the Apollo program was designed to have an almost spider-like appearance, as it was described by the Apollo 9 crew. Because the spacecraft was designed to work in a zone with no atmosphere, it didn't need to have smooth edges or an aerodynamic shape.

In addition to the bits of debris that speckle the "emptier" regions of space, research has shown that these areas are also home to different forms of radiation. In our own solar system, the solar wind — charged particles that stream from the sun — emanate throughout the solar system and occasionally cause auroras near Earth's poles. Cosmic rays also fly through our neighborhood, stemming from supernovas outside of the solar system.

In fact, the universe as a whole is inundated with what is known as the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which is essentially the leftover radiation from the explosion mostly commonly known as the Big Bang. The CMB is the oldest radiation that our instruments can detect.

Infographic: Cosmic Microwave Background Explained

Dark matter and energy

There remain two giant mysteries about space: dark matter and dark energy.

While scientists have provided extensive evidence for the existence of dark matter and dark energy, they are each still poorly understood as, so far, scientists cannot directly observe them and can only observe their effects.

Roughly 80% of all of the mass in the universe is made up of what scientists have dubbed "dark matter," but it's not known what it actually is or if it is even matter by our current definition. However, while dark matter doesn't emit light or energy and cannot, therefore, be directly observed, scientists have found overwhelming evidence that it makes up the vast majority of the matter in the cosmos.

Dark energy might have a similar name to dark matter, but it's a whole different component entirely.

Thought to make up nearly 75% of the universe, dark energy is a mysterious and unknown force or entity that scientists think is responsible for the universe's ongoing expansion.

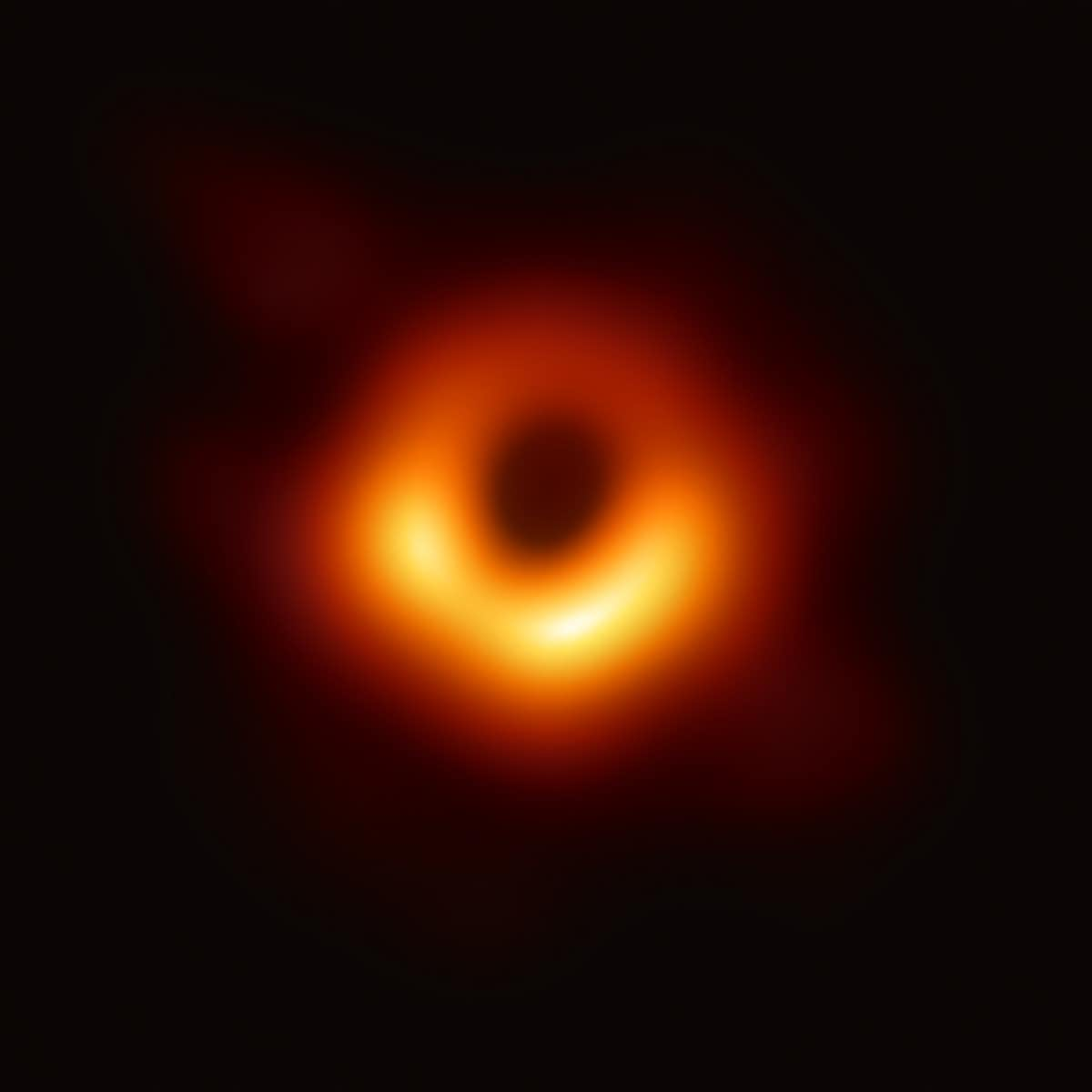

Black holes

Smaller black holes can form from the gravitational collapse of a gigantic star, which forms a singularity from which nothing can escape — not even light, hence the name of the object. No one is quite sure what lies within a black hole, or what would happen to a person or object who fell into it – but research is ongoing.

An example is gravitational waves, or ripples in space-time that come from interactions between black holes. This was first predicted by Albert Einstein at the turn of the last century, when he showed that time and space are linked; time speeds up or slows down when space is distorted.

As of mid-2017, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) Scientific Collaboration has announced three black-hole interactions and mergers detected through gravitational waves, in just two years.

The team found these three events in about two years, indicating that when LIGO is implemented at full sensitivity, the observatory may be able to find these sorts of events frequently, scientists said in May 2017. Should a bunch of these black hole events be detected, it could help scientists learn how black holes of a certain size (several tens of sun masses) are born, and later merge into new black holes.

Stars, planets, asteroids and comets

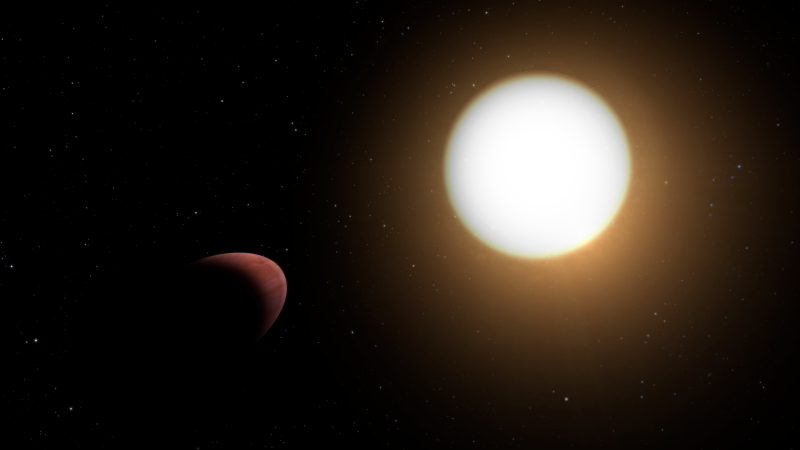

Stars (like our own sun) are immense balls of gas that produce their own radiation. They can range from red supergiants to cooling white dwarfs that are the leftovers of supernovas, or star explosions that occur when a big one runs out of gas to burn. These explosions spread elements throughout the universe and are the reason that elements such as iron exist. Star explosions can also give rise to incredibly dense objects called neutron stars. If these neutron stars send out pulses of radiation, they are called pulsar stars.

Planets are objects whose definition came under scrutiny in 2006, when astronomers were debating whether Pluto could be considered a planet or not. At the time, the International Astronomical Union (the governing body on Earth for these decisions) ruled that a planet is a celestial body that orbits the sun, is massive enough to have a nearly round shape, and has cleared its orbit of debris. Under this designation, Pluto and similar small objects are considered "dwarf planets," although not everyone agrees with the designation. After the New Horizons spacecraft flew by Pluto in 2015, principal investigator Alan Stern and others again opened up the debate, saying the diversity of terrain on Pluto makes it more like a planet.

The definition of extrasolar planets, or planets outside the solar system, is still not firmed up by the IAU, but essentially astronomers understand it to mean objects that behave like planets in our neighborhood. The first such planet was found in 1992 (in the constellation Pegasus) and since that time, thousands of alien planets have been confirmed — with many more suspected. In solar systems that have planets under formation, these objects are often called "protoplanets" because they aren't quite the maturity of those planets we have in our own solar system.

Asteroids are rocks that are not quite big enough to be dwarf planets. We've even found asteroids with rings around them, such as 10199 Charilko. Their small size often leads to the conclusion that they were remnants from when the solar system was formed. Most asteroids are concentrated in a belt between the planets Mars and Jupiter, but there are also many asteroids that follow behind or ahead of planets, or can even cross in a planet's path. NASA and several other entities have asteroid-searching programs in place to scan for potentially dangerous objects in the sky and monitor their orbits closely.

In our solar system, comets (sometimes called dirty snowballs) are objects believed to originate from a vast collection of icy bodies called the Oort Cloud. As a comet approaches the sun, the heat of our star causes ices to melt and stream away from the comet. The ancients often associated comets with destruction or some sort of immense change on Earth, but the discovery of Halley's Comet and related "periodic" or returning comets showed that they were ordinary solar system phenomena.

Galaxies and quasars

Among the biggest cosmic structures we can see are galaxies, which essentially are vast collections of stars. Our own galaxy is called the Milky Way, and is considered a "barred spiral" shape. There are several types of galaxies, ranging from spiral to elliptical to irregular, and they can change as they come close to other objects or as stars within them age.

Often galaxies have supermassive black holes embedded in the center of their galaxies, which are only visible through the radiation that each black hole emanates as well as through its gravitational interactions with other objects. If the black hole is particularly active, with a lot of material falling into it, it produces immense amounts of radiation. This kind of a galactic object is called a quasar (just one of several types of similar objects.)

Large groups of galaxies can form in clusters that are groups as large as hundreds or thousands of galaxies bound together gravitationally. Scientists consider these the largest structures in the universe.

This page was updated in Jan. 2022 by Space.com senior writer Chelsea Gohd.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

- Chelsea GohdSenior Writer