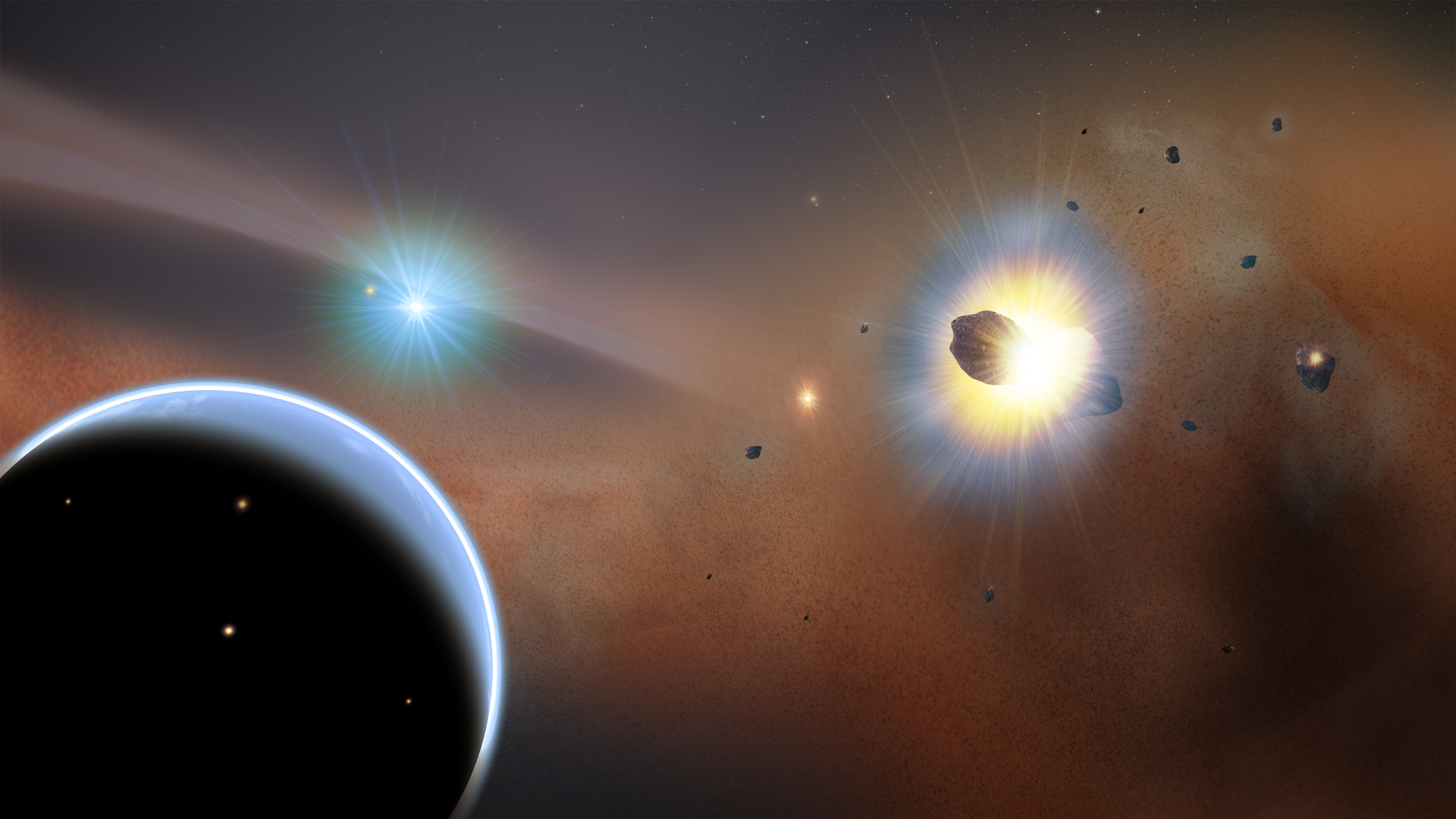

Astronomers have detected bizarre swarms of comets around a nearby star, icy bodies that may have been trapped by the powerful gravitational pull of a huge, undiscovered exoplanet.

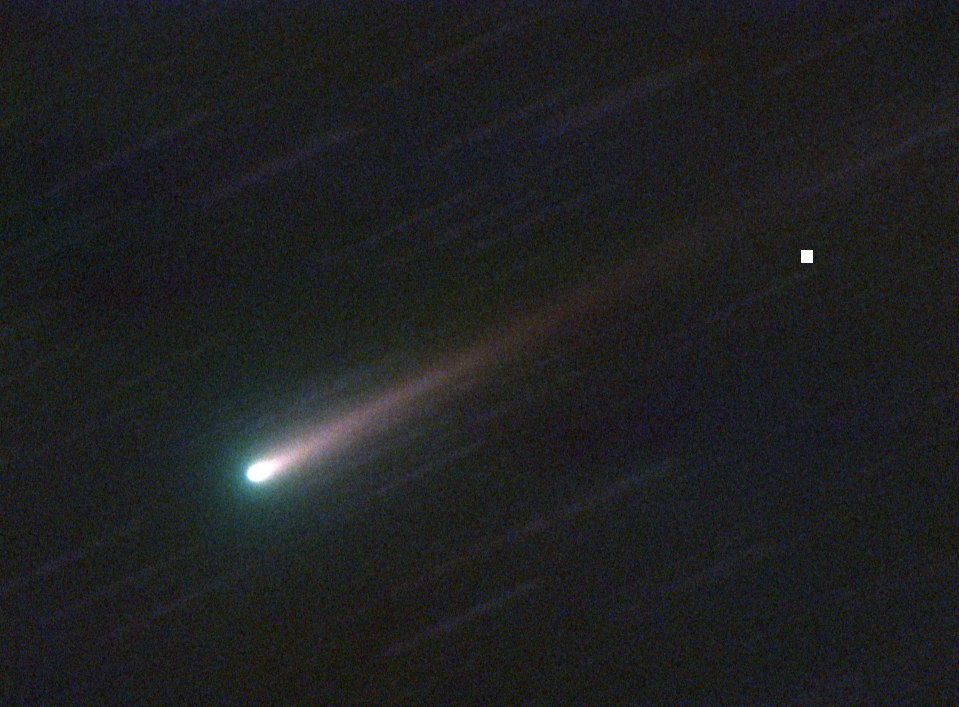

An international team of scientists spotted an enormous belt of carbon monoxide (CO) gas in the disk of debris surrounding Beta Pictoris, a young star that lies 63 light-years from Earth. The source of the gas is probably comets, and lots of them; one large comet must be getting destroyed every five minutes to keep replenishing the CO, which is destroyed by starlight, researchers said. You can see a video description of the mystery planet around Beta Pictoris here.

The swarms are likely corralled by a big, Jupiter-like alien planet orbiting far from Beta Pictoris, which is already known to host one gas giant (known as Beta Pictoris b) much closer in. [The Strangest Alien Planets]

"Detailed dynamical studies are now underway, but at the moment we think this shepherding planet would be around Saturn's mass and positioned near the inner edge of the CO belt," study co-author Mark Wyatt, from the University of Cambridge in England, said in a statement. "We think the Beta Pictoris comet swarms formed when the hypothetical planet migrated outward, sweeping icy bodies into resonant orbits."

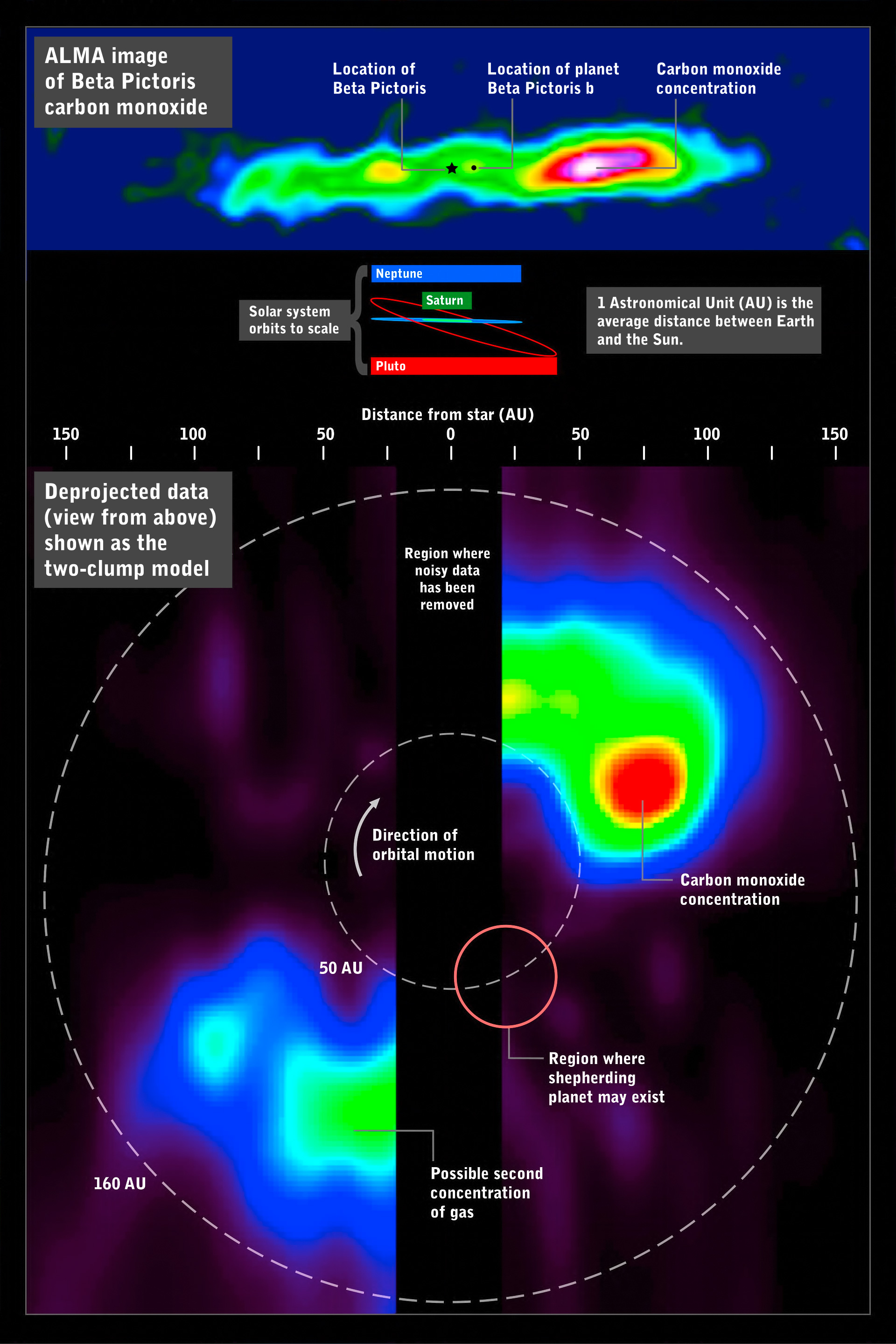

The astronomers used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile to map out millimeter-wavelength light from dust and carbon monoxide in the disk around Beta Pictoris, which is just 20 million years old.

ALMA's observations revealed a giant belt of CO totaling more than 200 million billion tons — about one-sixth the mass of Earth's oceans, researchers said. Much of the gas is contained in a single cloud 8 billion miles (13 billion kilometers) from the star. (For comparison, Earth orbits the sun at an average distance of 93 million miles, or 150 million km).

But there may actually be two clouds — and therefore two comet swarms — at this distance, researchers said. Because ALMA viewed the Beta Pictoris system edge-on, a separate cloud on the other side of the star may have been missed.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Researchers favor the two-cloud scenario, which implies the existence of a big exoplanet orbiting far from Beta Pictoris — perhaps 10 times farther away than Beta Pictoris b lies. This idea has a parallel in our own solar system: Jupiter has corralled the space rocks in the asteroid belt into two clumps, with one group leading and the other trailing as they cruise around the sun.

But the thinking changes if Beta Pictoris is determined to contain just a single comet swarm. In that case, the most likely explanation would be a mammoth smashup between two icy, Mars-size planets about 500,000 years ago, researchers said. Ongoing collisions among the fragments generated by this original crash could replenish the CO cloud.

The presence of CO around Beta Pictoris also suggests that the system may eventually become a good candidate to host life as we know it, researchers said.

"Carbon monoxide is just the beginning — there may be other more complex pre-organic molecules released from these icy bodies," co-author Aki Roberge, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., said in a statement.

The study was published online Thursday (March 6) in the journal Science.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.