Giant Balloon Trips to Near-Space: Q&A with World View CEO Jane Poynter

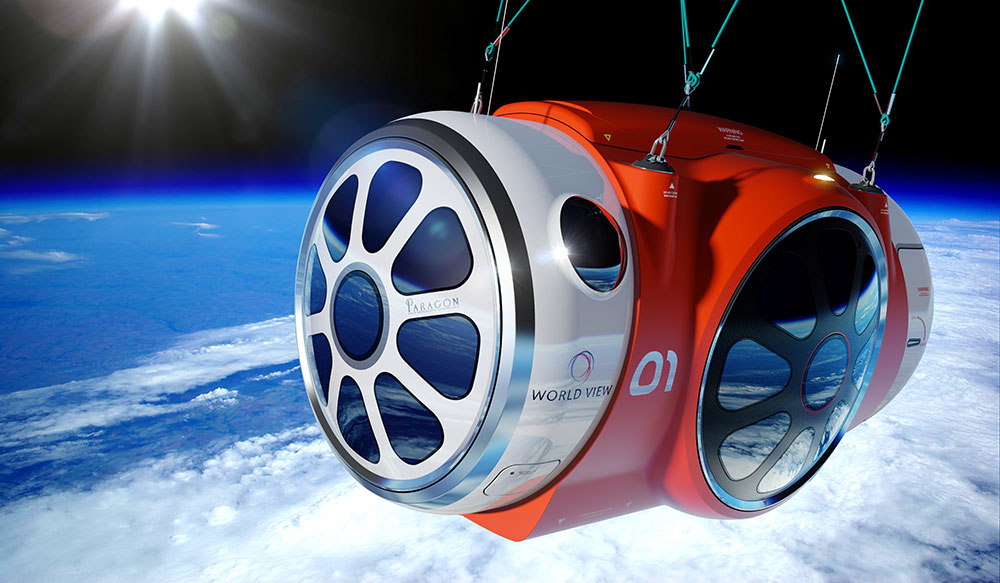

NEW YORK — By the end of 2016, private company World View hopes to take tourists to near-space — not with a rocket, but with a high-altitude balloon.

If World View's vision comes to fruition, customers paying $75,000 each will board a capsule and float 19 miles (30 kilometers) above the ground, a few miles shy of the height daredevil Felix Baumgartner dropped from in his space jump stunt. As they glide for up to two hours at maximum altitude, World View passengers will have a view of the blackness of space against the curvature of Earth — a sight usually only afforded to astronauts.

Without rockets and without the experience of weightlessness, World View's concept marks a departure from other space tourism ventures like Virgin Galactic and XCOR. Several passengers have already put down money for a ride and retired astronaut Mark Kelly has joined the team as director of flight crew operations. [World View's Near-Space Balloon Rides in Pictures]

As the Tucson-based company ramps up its testing, Space.com caught up with World View CEO Jane Poynter. Two decades ago, Poynter was one of eight people who spent two years inside Biosphere 2, a 3.15-acre sealed structure outside of Tucson, intended to be a closed ecological system. She also co-founded Paragon Space Development Corp., which is aiding private efforts to bring humans to Mars.

Space.com caught up with Poynter at the Explorers Club Annual Dinner here on March 15 to dicuss World View and space tourism. Her answers have been edited lightly for clarity and length.

Space.com: How did you come up with the concept of World View?

Jane Poynter: Taber MacCallum, who is our CTO, and I were both inside Biosphere 2. And when were in there we had this amazing experience of being part of our biosphere in an incredibly literal way, where we were drinking the same water over and over again and I knew that I was really, completely reliant on the plants and animals around me for my survival inside this system.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

I went into the Biosphere because I thought it was the closest I was ever going to get to Mars. I thought I was going to space, in a way, going inside Biosphere 2. But this experience also made me fall in love with the biosphere of planet Earth, and when I hear of astronauts talking about their experience of going into space, it seems incredibly analogous. So many of them go into space thinking that's what they're doing — they're going to space — and in fact what happens is they turn around and they see Earth and they fall in love with Earth, and it really changes the way they think about things. We want to be able to give that incredible experience to as many people as we can.

Space.com: Where are you now in your testing?

Poynter: We've done component testing and we're getting ready for a subscale test flight. We're doing a 10 percent scale test flight in about two months. Obviously there's no capsule on the bottom …. but there will be a parawing and a balloon above that if we want go through the full launch and landing.

Space.com: When World View is operational, where do you expect to take off with passengers?

Poynter: We're looking at a number of different launch sites. One of our primary launch sites looks to be Page, Ariz., and the reason is that studies have been done looking at the best weather to do this kind of thing and Page has a topographic anomaly that makes it have incredible weather for launching balloons. It then happens to be fairly closely to Las Vegas, so it's a very nice package.

Space.com: How many flights do you think you'll be running?

Poynter: The first year we're planning on about 50 flights. We don't expect that to be the demand. We want take it slow the first year and then build from that.

Space.com: Do you see the balloons having any scientific applications?

Poynter: Absolutely. We've already been talking with a lot of people that I can't necessarily name at this point. Of course, these balloons have been used for science already for decades so it's a very established market. We're going to be able to fly the size of payload that isn't really available at the moment. We can go all the way from 10 lbs. to 8,000 lbs. One of the interesting things about the capsule is that we can do human-tended research, kind of analogous to the way you would do it on the International Space Station, only you're doing it for much less cost.

Space.com: How did you get former NASA astronaut Mark Kelly on board?

Poynter: He's our director of flight crew operations, which we're really happy about. I've known Mark for a number of years. I've known Gabby [Giffords, his wife,] for even longer. I've known Gabby since before she was a congresswoman. And we're all in Tucson and we've been in the space business together for a long time, and he's just really fascinated with what we're doing — and I think he wants to fly.

Poynter: I don't think it's something that's going to make the mission fail, but I think it can be extremely hard on the crew. It was very hard on us. Perhaps we didn't prepare in as in-depth of a way as we could have. We did a lot of training in isolation, but there is a huge different between being out at sea for a month or being the Outback of Australia for a month and being isolated for months on end. It's that months on end.

There's a constellation of symptoms that tends to occur called isolated confined environment psychology and it tends to start occurring around the four to six month mark. That's the part that's difficult. It's really difficult to describe to people what happens. You kind of have to experience it to believe it. I'm sort of a happy-go-lucky kind of person. It never occurred to me that I would get depressed and all of that, and that's what happens.

Space.com: Would you do another long mission — perhaps a mission to Mars?

Poynter: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. It would be an incredible honor and extremely exciting to do.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @SPACEdotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.