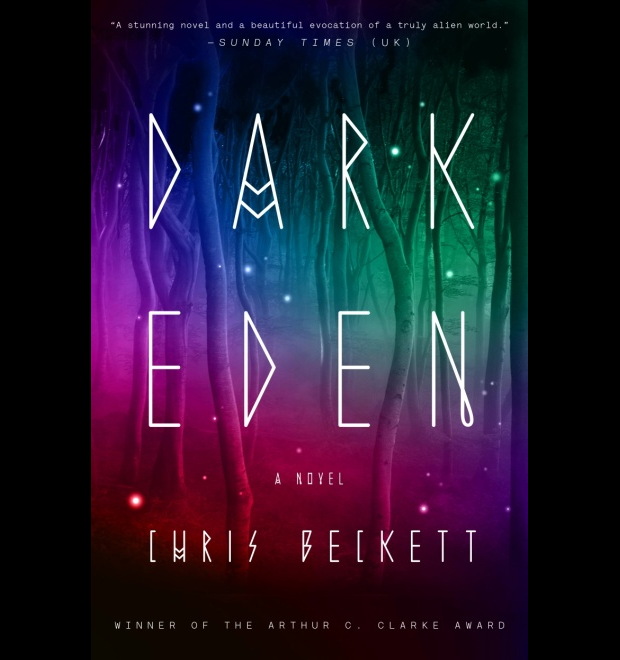

'Dark Eden' (US 2014): Book Excerpt

Chris Beckett is a university lecturer living in Cambridge, UK. His short stories have appeared in such publications as "Interzone" and "Asimov's" and in numerous "year’s best" anthologies in the United States. He contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

As space travel expands, so does the potential to ultimately reach other worlds — but if marooned there, can survivors expect the people of Earth to come looking for them? And how would the isolated generations that follow survive? Chris Beckett's novel "Dark Eden," winner of the Arthur C. Clarke award, explores what can happen to such a community, living at peace on an alien world until the prospect of rescue fades away.

Chris Beckett has been publishing short stories in magazines and anthologies since 1990. His story collection, The Turing Test, won the Edge Hill Short Fiction Award in 2009. His third novel, "Dark Eden," has received critical acclaim since its publication in the UK in 2012. Dark Eden's sequel, "Mother of Eden," will appear in 2014. [Related: Interview with Chris Beckett on "Dark Eden"]

----------------------------------------

1. John Redlantern

THUD, THUD, THUD. Old Roger was banging a stick on our group log to get us up and out of our shelters.

"Wake up, you lazy newhairs. If you don’t hurry up, the dip will be over before we even get there, and all the bucks will have gone back up Dark!”

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Hmmph, hmmph, hmmph, went the trees all around us, pumping and pumping hot sap from under ground. Hmmmmmmm, went forest. And from over Peckhamway came the sound of axes from Batwing group. They were starting their wakings a couple of hours ahead of us, and they were already busy cutting down a tree.

“What? ” grumbled my cousin Gerry, who slept in the same shelter as me. “I’ve only just got to sleep!”

His little brother Jeff propped himself up on one elbow. He didn’t say anything, but watched with his big interested eyes as Gerry and I threw off our sleep skins, tied on our waistwraps, and grabbed our shoulder wraps and our spears.

“Get your arses out here, you lazy lot!” came David’s angry spluttery voice. “Get your arses out fast fast before I come in and get you.”

Gerry and me crawled out of our shelter. Sky was glass-black, Starry Swirl was above us, clear as a whitelantern in front of your face, and the air was cool cool as it is in a dip when there’s no cloud between us and stars. Most of the grownups in the hunting party were gathered together already with spears and arrows and bows: David, Met, Old Roger, Lucy Lu . . . A bitter smell was wafting all around our clearing, and the smoke was lit up by the fire and the shining lanterntrees. Our group leader Bella and Gerry’s mum, my kind ugly aunt Sue, were roasting bats for breakfast. They weren’t coming with us, but they’d got up early to make sure we had everything we needed.

“Here you are, my dears,” said Sue, giving me and Gerry half a bat each: one wing, one leg, one tiny little wizened hand.

Ugh! Bat! Gerry and me pulled faces as we chewed the gristly meat. It was bitter bitter, even though Sue had sweetened it with toasted stumpcandy. But that was what the hunting party was all about. We were having bat for breakfast because our group hadn’t managed to fi nd better meat in forest round Family, so now we were going to try our luck further away, over in Peckham Hills, where woollybucks came down during dips from up on Snowy Dark.

“We won’t walk up Cold Path to meet them,” said Roger, “we’ll go up round the side of it, up Monkey Path, and then meet Cold Path at the top of the trees.”

Whack! David hit me across the bum with the butt of his big heavy spear and laughed.

“Wakey, wakey, Johnny boy!”

I looked into his ugly batface—it was one of the worst batfaces in Family: it looked like he had a whole extra jagged mouth where his nose should be—but I couldn’t think of anything to say. There was no fun in the man. He’d hit you hard for no reason, and then laugh like he’d made a joke.

But just then a bunch of Spiketree newhairs arrived in our clearing with their spears and bows, walking along the trampled path that linked our group to theirs on its way to Greatpool.

“Hey there, Redlanterns!” they called out. “Aren’t you ready yet?”

Bella had agreed with their group leader Liz that some of them could come along with us and take a share of the kill. They were the group next to us Redlanterns in Family and, for the present, they were keeping the same wakings and sleepings as us, which made it easy for us to do things together with them (easier than with, say, London group, who were having their dinner when we were just waking up).

I noticed Tina was among them: Tina Spiketree, who cut her hair with an oyster shell to make it stick up in little spikes.

“Everyone ready then?” Bella called. “Everyone got spears? Everyone got a warm shoulder wrap? Good. Off you go then. Go and get us some bucks, and leave us in peace to get on with things back here.

We went out by a path that led through a big clump of flickering starflowers and then into Batwing. A whole bunch of Batwing grownups and newhairs were in their clearing banging away at a giant redlantern tree with their blackglass axes, working in the pink light of its flowers. We walked round the edge of their clearing to Family Fence, dragged away the branches at the opening, and went out into open forest. No more shelters and campfires ahead of us now: nothing but shining trees.

Hmmmph, hmmmph, hmmmph, went the trees. Hmmmmmm, went forest.

We walked for a waking under the light of the treelanterns, slashing down whatever birds and bats and fruit we could get as we went along, and finally stopped to rest at the big lump of rock called Lava Blob. Old Roger handed us out a gritty little seedcake each, made of ground-up starflower seeds, so we could have something in our bellies, and then we settled down with our backs against the rock, so we didn’t have to worry about leopards sneaking up behind us. There were lots of yellowlantern trees round there, which we didn’t get so much back in Family, and also yellow animals called hoppers that came bouncing out of forest on their back legs and wrung their four hands together while they looked at us with their big fl at eyes and went Peep peep peep. But hoppers were no good to eat and their skins were no use either, so we just chucked stones at them to make them go away and let us sleep in peace.

When we woke up, Starry Swirl was still bright bright in sky. We ate a bit of dry cake and off we went again, under redlanterns and whitelanterns and spiketrees, with fl utterbyes darting and glittering all round us and bats chasing the fl utterbyes and trees going hmmph, hmmph, hmmph like always, until it all blurred together into that hmmmmmmmmm that was the background of our lives.

After a few miles we came to a small pool full of shiny wavyweed and all us newhairs took off our wraps and dived into the warm water for crabfish and oysters to eat. All the boys watched Tina Spiketree diving in, and they all thought how graceful she was with her long legs, and how smooth her skin was, and how much they wanted to slip with her. But when she came up she swam straight to me, and gave me a dying oyster with the bright pink light still shining out of it.

“You know what they say about oysters, don’t you, John?” she said.

Tom’s neck, she was pretty pretty, the prettiest in whole of Family. And she knew it well well.

In another couple of hours we reached the place where Peckham Hills began to rise up out of forest of Circle Valley, and started to climb up through them by Monkey Path, which isn’t really a path, but just a way we know through the trees. The trees carried on up the slopes—redlanterns and whitelanterns and scalding hot spiketrees—and there were flickering starflowers growing beneath them, just like in the rest of forest. Streams ran through them down from darkness and ice, heading toward Greatpool, still cold cold but already bright and glittering with life. And small creatures called monkeys jumped from tree to tree. They had little thin bodies, and six long arms with a hand on the end of each. Handsome Fox shot one with an arrow, and was pleased pleased with himself, even though they were all bones and sinews and only give a mouthful of meat, because they move fast and are hard to aim at with those big blotches on their skin that fl ash on and off as they swing among the lanternflowers.

As we climbed up it got colder. The starfl owers disappeared, the trees became smaller, and there weren’t any monkeys anymore, only the occasional smallbuck darting away through the trees. And then the trees stopped and we came out from the top edge of forest onto bare ground. Pretty soon, when we’d climbed above the height of those last few little trees, we could see whole of Circle Valley spread out below us—whole of Eden that we knew, with thousands and thousands of lanterns shining all the way from where we stood on Peckham Hills to Dark shadow of Blue Mountains away in the distance, and from Rockies over the left, with the red glow of Mount Snellins smoldering in middle, to the deep darkness over to our right that was Alps. And above all of it the huge spiral of Starry Swirl was still shining down.

Of course, with no trees to give off light with their lanternflowers or to warm the air with their trunks, it was dark dark up there—you could only just barely make things out in the starlight and the light from the edge of forest—and it was cold cold, specially on our feet. But us newhairs dared each other to run up as far as the snow. The ice felt like it was burning, it was so cold, and most kids took ten twenty steps, yelled and came running down again. But I took Gerry right up to the ridge of the hill and then, ignoring Old Roger yelling at us to come back, went far enough down the other side so that the others couldn’t see us.

“We’ve made our point now, haven’t we, John?” Gerry said, shivering. We only had waistwraps on, and buckskins round our shoulders, and our feet were hurting like they’d been skinned. “Shall we go back down to rest of them now?”

My cousin Gerry was about a wombtime younger than me—his dad was giving his mum a slip, in other words, about the time that I was born—and he was devoted to me, he thought I was wonderful, he’d do just about anything I asked.

“No, wait a minute. Wait a minute. Be quiet and listen.”

“Listen to what?”

“To the silence, you idiot.”

There was no hmmmmmmmm of forest, no hmmph, hmmph, hmmph of pumping trees, no starbirds going hoom, hoom, hoom in the distance, no flutterbyes flapping and flicking, no whoosh of diving bats. There was no sound at all except a quiet little tinkle of water all around us coming out from under the snow in hundreds of little streams. And it was dark dark. No tree-light up there. The only light came from Starry Swirl.

We could barely make out each other’s faces. It made me think about that place called Earth where Tommy and Angela first came from, way back in the beginning with the Three Companions, and where one waking we would all return, if only we stayed in the right place and were good good good. There were no lanterntrees back there on Earth, no glittery flutterbyes or shiny flowers, but they had a big big light that we don’t have at all. It came from a giant star. And it was so bright that it would burn out your eyes if you stared at it.

“When people talk about Earth,” I said to Gerry, “they always talk about that huge bright star, don’t they, and all the lovely light it must have given? But Earth turned round and round, didn’t it, and half the time it wasn’t facing the star at all but was dark dark, without lanterns or anything, only the light the Earth people madefor themselves.”

“What are you talking about, John?” Gerry said, with his teeth chattering. “And why can’t we go back down again if you just want to talk?”

“I was thinking about that darkness. They called it Night, didn’t they? I’m just thinking that it must have been like this. What you get up here on Snowy Dark: it’s what they would have called Night.”

“Hey John!” Old Roger was calling from the far side of the ridge. “Hey Gerry!” He was scared we’d freeze to death or get lost or something up there.

“Better go back,” Gerry said.

“Let him stew a minute first.”

“But I’m freezing freezing, John.”

“Just one minute.”

“Okay, one minute,” said Gerry, “but that’s it.”

He actually counted it out on his pulse, one to sixty, the silly boy, and then he jumped up and we both climbed back over the ridge. Gerry went running straight down to the others, but I stood up there for a moment, partly to show I was my own man and didn’t go scurrying back for Old Roger or anyone, and partly to take in how things looked from up there on top of the ridge: the shining forest, with darkness all around it, and above everything the bright bright stars. That’s our home down there, I thought, that’s our whole world. It felt weird to be looking in on it from outside. And though in one way the bright forest stretching away down there seemed big big, in another way it seemed small small, that little shining place with the stars above it and darkness looking down on it from the mountains all around.

Back with the others, Gerry made a big thing about his freezing feet, asking some people to feel them and rub them, begging others to let him ride on their backs until he had warmed up, and generally hopping and skipping around like an idiot. That was how Gerry dealt with people. “I’m just a fool, I won’t hurt anyone,” that was his message. But I wasn’t like that. “I’m not a fool by any means,” was my message, “and don’t assume I won’t hurt you either.” I acted as if I didn’t feel the cold in my feet at all, and pretty soon they were so numb anyway that I really didn’t. I noticed Tina watching me and smiling, and I smiled back.

On we went, just below the snow and along the top edge of forest, where there was a bit of light from the trees, Old Roger grumbling and moaning about how newhairs had no respect anymore and things were different from how they used to be. “Old fool was scared he’d have to go back to Family and tell your mums he’d lost you,” said Tina. “He was thinking of the trouble he’d be in. No more slippy for Old Roger.”

“Like he gets it anyway,” said dark-eyed Fox, who my mum had told me once with a shrug was like as not my father. (But then another time she said it could have been Old Roger—he wasn’t quite such a fool once apparently—or maybe a pretty little newhair boy from London she once slipped with. I wished I knew, but lots of people didn’t know for sure who their dad was.)

We came to Cold Path, which ran down beside a stream that carried meltwater from a big snowslug. Woollybucks made this path, and we crept up to it in case there were some on it now. There weren’t, but there were lots of fresh buck tracks coming down off the snow and onto the muddy ground beside the stream as it headed down to forest below. The bucks had come down already. The dip had brought them down from wherever it was up there they normally lived, and from whatever it was that they normally did up there.

“I saw a big big bunch of them in this exact spot once,” said Roger. “Coming down the path from the snowslug there. About ten fifteen wombs ago. There were ten twelve of them, plodding down in single file from up on Snowy Dark there and . . .”

I stopped listening then. I looked up into the blackness of Snowy Dark as he talked, and wondered. No one knew anything about that place up there except that it was high high and dark dark and cold cold cold, and that it was the source of all the streams and the great snowslugs (“glay seers,” as Oldest called them), and that it surrounded our whole world.

But then I noticed a light high up there in sky: a little far-off patch of pale white light hovering up there in darkness.

“Hey look! Up there!”

Normally when you see something that you don’t know what it is, it only takes a second or two before you do know, or at least can have a good guess. But this I couldn’t make out at all. I really had no idea what it could possibly be. I mean, there’s one source of light in sky: Starry Swirl. And there’s another source on the ground:

living things, trees and plants and animals, plus the fires we make ourselves. But the only light I’d ever seen in between these two sources was from volcanoes like Mount Snellins, and they were red red like fire, not pale and white.

It sounds dumb but all I could think of for a moment was that it was a Landing Veekle, one of those sky-boats with lights on them that brought Tommy and Angela and the Three Companions down to Eden from the starship Defiant.

Well, we were always taught that it would happen sometime. The Three Companions had gone back to Earth for help. Something must have gone wrong, we knew, or the Earth people would have come long ago, but they had a thing with them called a Rayed Yo that could shout across sky, and another thing called a Computer that could remember things for itself. A waking would come when they’d find Defiant, or hear the Rayed Yo, and build a new starship and come for us, across Starry Swirl, through Hole-in-Sky, to take us back to the bright light of that giant giant star.

And for one sweet scary moment I thought it was fi nally happening now.

Then Roger spoke.

“Yeah,” he said. “That’s them. That’s woollybucks alright.”

Woollybucks?

Well, of course that’s all it was! It was obvious now. That pale light wasn’t really in sky at all, it was up in the mountains, up on Snowy Dark, and it was just woollybucks. Michael’s names, I was glad I hadn’t said anything out loud. Woollybucks were the one thing we were supposed to be looking for, and I’d mistaken them for sky people from bloody Earth!

I felt a fool, but beyond that I felt sad sad, because for a few seconds I’d really thought that the time had finally come when we would find our way back to that place full of light and people, where they knew the answers to all the hard hard questions we had no idea how to solve, and could see things we can’t see any more than blind people . . . But no, of course not. Nothing had changed. All we still had was Eden and each other, five hundred of us in whole world, huddled up with our blackglass spears and our log boats and our bark shelters.

It was disappointing. It was sad sad. But it was still amazing just to think the mountains up there were so high. I mean, you could see their shadows against the stars from back in Family, and you could see they must be big big, but you couldn’t see the mountains themselves, only the lower slopes where there were still trees and light, and you couldn’t really tell which were the mountains and which were the clouds above them. I’d only ever been to the lower hills before and I’d imagined that Snowy Dark behind them was maybe two three times higher than that ridge of hills that Gerry and I had run up to the top of. But I could tell now that it was ten twelve times that high.

And right up there—so high up, so far away, in a place so different from where we were now that it was more like looking into a dream than at a real place in the world—a row of woollybucks were moving in single file across the slope, and the soft white lanterns on the tops of their heads were lighting up the snow around them.

Just for a moment as the bucks went past, the snow shone white, and then it became gray, and then it went back into blackness again. And though woollybucks are big beasts, two three times the weight of a man, they looked so tiny and alone up there in their tiny little pool of light that they might as well have been little ants. They might as well have been those little flylets that live behind the ears of bats.

And in the back of my mind a little thought came to me that there were other worlds we could reach that weren’t hidden away in Starry Swirl, or through Hole-in-Sky, but here on ground, in Eden. They were the places where the woollybucks went, the places they came from.

“There were about twelve thirteen bucks that time I was telling you about,” Old Roger said. “They came down here and we did for four of them before the rest ran away back up the hill where we couldn’t follow. You know old Jeffo London, the bloke with one leg that makes the boats? Well, he had two legs back then and he got a bit overexcited and went after the other seven eight bucks. He got lost up there in Dark. We waited as long as we could, but pretty soon we were freezing too, so we went down the path a bit and waited there for him. No one thought he’d make it back but, just before we were about to head back to Family with the bucks, he bloody did! He came stumbling down the path with these kind of white burns on his toes and his leg. It turned to black after a while—a black burn, though they call it gang green for some reason—and that’s why he’s only got one leg. We had to cut off the other one, saw it off with a blackglass knife. Harry’s dick! You should have heard him yell. But the rest of us, well, we were pretty happy to be going back with all that buckmeat. And we were popular when we got back, I can tell you. We were happy. Slippy all round, I reckon. I know I . . .”

“Yeah alright, Roger,” David interrupted. He didn’t like it when people laughed and joked about having a slip. “Alright Roger, that’s interesting I’m sure, but that lot’s not coming down, are they?”

Old Roger peered up at Snowy Dark and pretended to look. He was at that age when folk start going blind: eighty wombtimes old or thereabouts. He didn’t want us to know how bad it had got in case we decided he shouldn’t be the head huntsman for our group anymore—which he really shouldn’t have been—so no way was he going to let on that all he could really see was a blur. “No, I suppose,” he said, “it’s . . . um . . . always hard to tell with woollybucks.”

This is nuts, I thought, letting this old man lead us. Food was getting scarcer in our group and Family in general. Not really scarce, but we all went a bit hungry some wakings. And yet who did we send out to lead a woollybuck hunt for our group? This blind old fool!

"They're headed away from us," David said coldly. "So we'd better get down again and try and get the ones that came down earlier."

"How do you know that lot up there aren't the same ones that came down?" asked Met. He was a big tall boy who wasn't all that bright, and didn’t often speak. "Maybe they've been down already and now they're going up again?"

"Look at the tracks, Met," said David, poking Met hard in the arm. "Look at the bloody tracks. They're all going downhill, aren't they? There's none coming up. Look at the way the toes are pointed, Einstein. So that means a bunch of them are still down there, doesn't it? And I'd say they’ll stay down there too while Starry Swirl is still out."

"Couldn't we wait here until they come back up again?" asked Met.

It was a stupid suggestion. All the wraps we had to cover ourselves with were our bitswraps round the middle and a buckskin round the shoulders, and our feet were bare and cold.

"Oh clever," said David, and he looked at Met with his smile that wasn’t really a smile, wind whistling in and out of his ugly hole of a face, with that other bit of mouth that went up where a nose should be and always seemed red and sore. "Stay up by all means, Met, but I don't think I fancy a dose of gang green myself."

He was always a sarcastic bastard. But that, and hitting people, was about the nearest he got to being friendly.

"Anyone want to freeze up here with Met, go ahead," David said. "Otherwise let's get down out of the cold to where the woollybucks actually are, eh?"

It was cold cold. Even if you put your back against a tree trunk it was cold, because they were only stumpy little trees up there and they didn't give out heat like a big redlantern or whitelantern does down in the valley. But then again, I thought to myself, Met's idea wasn't so dumb. If we could only find a way of staying up there for a bit longer we could spear loads loads more bucks, because they always did come up and down these paths down from Dark around dips. So why didn't we think about ways of keeping warm up there? Why didn't we bring some more wraps with us, or make wraps that we could tie up round us? Why hadn't we found a way of putting wraps round our feet? Why had we decided that it was too bloody cold and difficult up by Dark to even try and work out a way round it?

But that was how it was. We walked down beside the stream again and pretty soon tall trees were all around us again, there were lanterns wherever we looked, white and red and blue, and that little crack in the hills had widened out into Cold Path Valley. It was a small place: in an hour you could walk right across it to the narrow little gap in the hills that led back into Circle Valley where we lived.

"I wonder where the woollybucks go," I said. "I wonder if there's another forest they go to beyond the hills."

"Another forest?" snorted Fox. "Don't be daft, John. There couldn’t be anywhere else as big as Circle Valley."

"That’s wrong! When Tommy and Angela and the Three Companions first saw Eden, they saw lights all over ..."

"Beyond the hills the Shadow People live," Lucy Lu interrupted me in a loud slow dreamy voice.

She was a woman with a round pale face and watery eyes who used to go round the other groups in Family and offer to talk to the shadows of their dead in exchange for bits of blackglass and old skins and scraps of food.

"That's crap," said Tina. "There's no such thing as Shadow People."

I agreed with her. I'd got no time for things that people saw out of the corner of their eye, or in dreams. Harry's dick, there were enough real things to look at face on! There were enough things you could put your hands on and hold.

"You wouldn't say that if you saw them like I do," said Lucy Lu in that dreamy voice, like she was only half in our world and half in a shadow world which only she could see.

"Some people reckon sky is a huge fl at stone," Gerry broke in suddenly, "and Starry Swirl is rocklanterns growing underneath it, like you get in caves. This big flat stone, it sits up there with its edges on the top of Snowy Dark. Dark is really there to hold it up."

"That is really crap," said Tina with her throaty laugh. "Boy, that really is. And no one else even says it either apart from you, Gerry. You made it up just now. Trying to be different like your hero John."

"No I didn't!" Gerry laughed.

He was happy to have headed off an argument between me and Lucy Lu and Fox.

"Of course you did," Tina told him. "It's the most half-arsed thing I ever heard."

"Yes, and make sure you don't say that sort of thing in front of Oldest either," said Old Roger. "They wouldn't like it. How could Tommy and Gela have come down from Starry Swirl with the Three Companions if it was just rocklanterns on a stone?"

"So Gerry can't have his own ideas?" I said. "But Oldest can make up any fairy story they like and then force us all to accept that it's true?"

"You watch it, John," said David. "You bloody watch what you say."

"Newhairs!" complained Old Roger. "When I was young we showed respect to our Oldest. We’d never say the True Story was made-up."

I didn't really think it was made up. I didn’t doubt that Tommy and Angela and the Three Companions had come down from sky. We had the Mementoes after all, we had the Earth Models, we had old writing and pictures scratched on trees. We had all kinds of reasons for believing it was true. I just didn’t like the way that some people were allowed to take that old story and keep it for themselves and make it say what they wanted it to say.

Excerpted from "Dark Eden," a novel by Chris Beckett. Copyright © 2012 by Chris Beckett. Published by Broadway Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.