How Albert Einstein Helped Blackmail President Roosevelt Over Manhattan Project Funding

Seventy-five years ago, Hungarian-American physicist Leo Szilard wrote a letter to United States President Franklin Roosevelt expressing concern that German scientists would soon unlock the secrets to developing the first atomic bomb.

Concerned that his relative anonymity would cause the warning to go unheeded, Szilard persuaded his friend and colleague Albert Einstein to sign the letter. The Einstein-Szilard letter resulted in the establishment of the Manhattan Project, and the United States' subsequent creation of the world's first nuclear weapon.

But that wasn't the only letter penned by the pair. Szilard and Einstein actually drafted four missives to the president. [The 10 Biggest Explosions Ever]

"The third is probably the most interesting, because it involves a bit of scientific and political blackmail," author William Lanouette said at a press conference on April 7 during a meeting of the American Physical Society in Savannah, Georgia. Lanouette is the author of "Genius in the Shadows: A Biography of Leo Szilard, the Man Behind the Bomb" (University of Chicago Press, 1994).

Government blackmail

Szilard studied in Berlin with Einstein and Max Planck, among other notable scientists. According to Lanouette, he fled Germany with Einstein to avoid Nazi persecution.

While in London in 1933, Szilard conceived the idea of a nuclear chain reaction, filing a patent for the process a year later. In 1936, he assigned the patent to the British Admiralty to keep it secret, in an effort to keep Germany from being the first to develop an atomic bomb.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But by 1939, when Szilard had moved to the United States, Germany had made significant progress. German scientists had split the uranium atom less than a year before the nation's army invaded Poland.

At that point, Szilard met with Einstein to write the first and most famous of the Einstein-Szilard letters, warning President Roosevelt about the German efforts to formulate the atomic bomb, and the possible disastrous outcomes should this come to pass. The result was a promise to fund research into nuclear fission, which occasioned the second Einstein-Szilard letter thanking the president.

Szilard had written an article for the Physics Review detailing how a chain reaction would work, but asked the journal to hold up publication so that Germany and other countries would not be alerted.

Time passed, but the scientists did not receive the money promised by President Roosevelt. So Szilard approached Einstein and suggested that if the government didn't follow through with the funding, he would allow the article to be published.

"For people of such high ideals to, in effect, blackmail the government with information about how to make a nuclear weapon was quite surprising," Lanouette said.

The government apparently took the threat to heart, coughing up the funds for research that ultimately led to the creation of the Manhattan Project in the early 1940s.

Second thoughts

As work progressed, Szilard began to have second thoughts about the creation of the bomb. Originally, he had been focused on the concept of self-defense, hoping to ensure that Germany wasn't the first and only country to build such a powerful weapon. With the German surrender looming in the spring of 1945, he questioned the need for the weapon.

In the fourth and final Einstein-Szilard letter, the pair attempted to set up an appointment with the president to discuss their concerns. However, Roosevelt died before the meeting could be kept, and his successor, President Harry Truman, set Szilard up with James Byrnes, the soon-to-be Secretary of State.

"The clash of the scientist who wanted to make the bomb and then wanted to stop versus the politician who couldn't wait to use it is really quite a dramatic event in itself," Lanouette said.

In June 1945, Szilard helped to author the Franck Report, warning that even if the atomic bomb helped to save lives during the present war, it could ultimately lead to a nuclear arms race and perhaps even a nuclear war with far more devastating results.

"He was shy, a bit eccentric, and always thinking five to 10 years ahead of time," Lanouette said. [Doomsday: 9 Real Ways the Earth Could End]

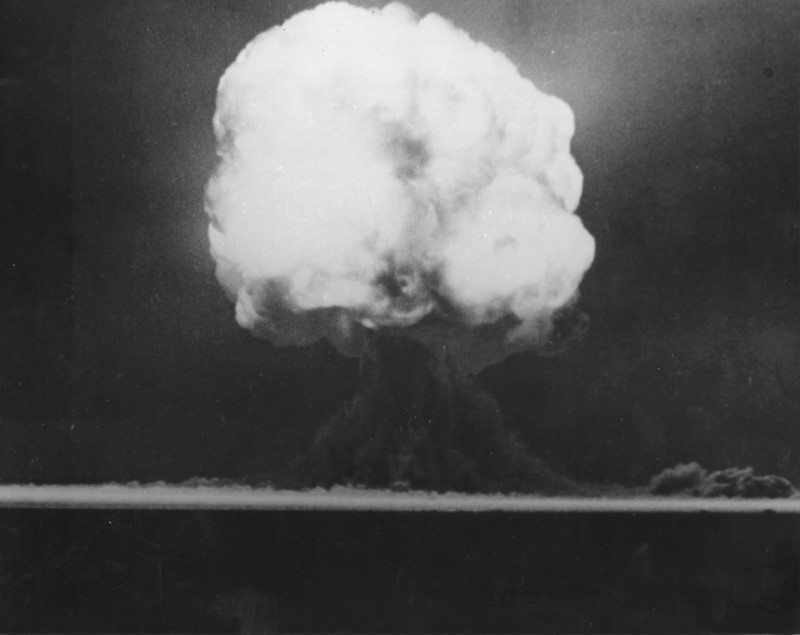

The United States, of course, decided to go ahead and use the weapon during the final stages of World War II, dropping one atomic bomb each on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

According to Lanouette, Albert Einstein, who had no direct involvement with the Manhattan Project, said, "My only activity in creating this weapon was to be Leo Szilard's mailbox."

When the war was won

After the war, Szilard continued his efforts to stem the rising tide of nuclear weapons. He often spoke in public, and authored a number of satires, including one in 1947 titled "My Trial As a War Criminal."

That short story describes how, after the Russians won World War III, they rounded up all of the people who worked on the atomic bomb, including Szilard, and put them on trial as war criminals.

"It was his way of pointing out that scientists do have responsibilities for their effects," Lanouette said.

Szilard also founded the Council for a Livable World, which today continues to work for peace.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd