Best Time to Observe the Moon This Month Is Now

As the moon moves from first quarter to full moon over the next week, it offers stargazers a wonderful opportunity to explore another world.

As the moon moves in its orbit around the Earth, it gradually exposes more of its Earth-facing side to the rays of the rising sun. Even the smallest amateur telescope will reveal an amazing amount of detail on the moon's surface, as the topography is thrown into relief by the sun's glancing rays. This is a better time to look at the moon than at full moon, when the sunlight is coming from directly overhead.

The most obvious feature of the moon is the variation in its surface color. The mountainous regions, mostly on the southern half of the visible face, are a brilliant white, while the level plains that dominate its northern half are a darker grey. These color differences are even visible with the unaided eye, and their pattern makes up "the man in the moon." [The Moon: 10 Surprising Lunar Facts]

What formed the craters of the moon? Most are thought to be the result of bombardment by asteroids and meteoroids billions of years ago. Some enclose the rugged aftermath of these impacts while others have smooth floors where lava has flowed to create an even surface. In other cases, lava from larger impacts has swept over more ancient craters.

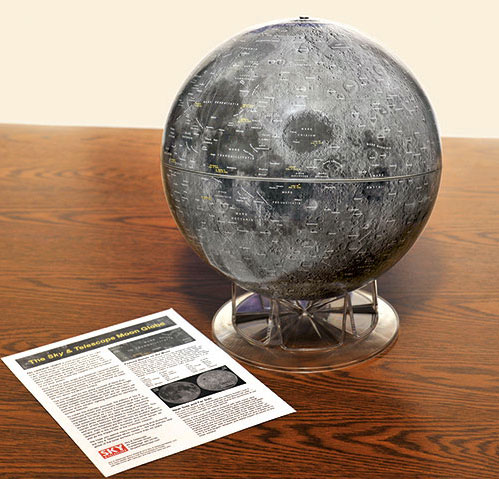

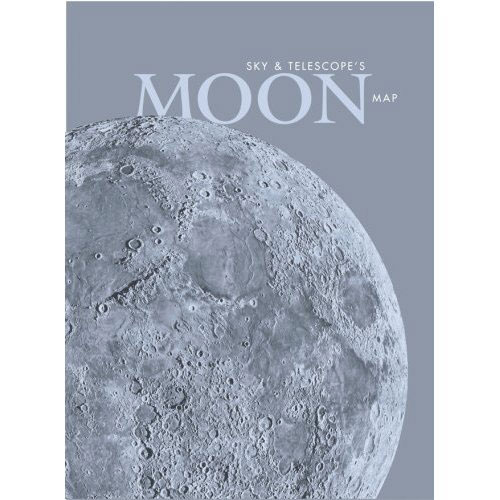

It helps to learn the locations of some of the more prominent craters on the moon's surface, as these provide landmarks for smaller features, just as the bright stars in the sky serve as landmarks for star hopping to deep sky objects.

North of Copernicus lies the Mare Imbrium, the so-called Sea of Rains. It got this name before it was known that the moon was an airless world with its water locked deep within its rocks. In reality, the moon has no seas, and rain never falls there. The north "shore" of the Mare Imbrium is marked by the graceful curve of the Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. This is in fact the ghost of a gigantic crater, 160 miles (260 km) in diameter, long filled by the flow of lava from the Mare Imbrium.

Also on the north shore of the Mare Imbrium is the perfect oval of the crater Plato, named for the Greek philosopher. This crater, which is slightly larger than Copernicus, is 63 miles (101 km) in diameter. Unlike Copernicus' rugged floor, Plato's floor is a smooth expanse of lava, marked only by a few tiny craterlets. These provide an excellent test for telescope optics, since they are only a few miles in diameter. [Best Night Sky Events of May 2014 (Gallery)]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The area toward the moon's south pole is mountainous and crammed with craters. One of the brightest and most recent is Tycho, 53 miles (85 km) in diameter, named for the Danish observer Tycho Brahe, whose planetary measurements paved the way for Kepler's mathematical solution to the movements of the planets. Like Copernicus, this has a complex terraced structure. At full moon, it is surrounded by a bright system of rays. Material from the impact was ejected in all directions and traveled far around the moon because of its low gravity.

Between Tycho and the moon's north pole lies the mighty lunar crater Clavius, 140 miles (225 km) in diameter. Moonwatchers like to see how many craterlets they can count within Clavius' walls.

As the sun rises further in the next few days, observers will spot Gassendi in the southwest quadrant of the moon. This is a huge ruined crater 68 miles (110 km) in diameter. Its floor is marked by several mountain peaks and a complex system of rilles — linear features caused by the collapse of lava tubes below the surface. If you catch Gassendi just right as the sun is rising across its floor, you may see the strange doughnut-shaped mound on the northern half of its floor, discovered by Canadian amateur astronomer George Wedge.

With a good map of the lunar surface, see how many of the smaller craters you can identify. On a night with steady seeing and an excellent telescope, every part of the lunar surface appears like the surface of a gritty pumice stone, pitted with smaller and smaller craters down to the limits of visibility. No other world offers us this wealth of detail.

Editor's Note: If you snap an amazing photo of the moon, or any other night sky target, and you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.