Two huge radio telescopes have given scientists a rare look beneath the surface of the moon.

Signals beamed from the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico — the world's largest radio dish, with a diameter of 1,000 feet (305 meters) — penetrated deep into the moon. They then bounced back and were detected by the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, the planet's biggest, fully steerable radio telescope at 330 feet (100 m) wide.

Researchers use this technique, called bistatic radar, to study many solar system objects, from asteroids to other planets. In this case, it revealed subsurface details in two lunar locales, the Sea of Serenity and a crater called Aristillus.

The new radar observations allow scientists to peer 33 to 50 feet (10 to 15 m) beneath the Sea of Serenity, which is near the site where NASA's final manned lunar effort, the Apollo 17 mission, touched down in December 1972. Light and dark areas visible in the images reveal details of rock and dust composition, researchers said.

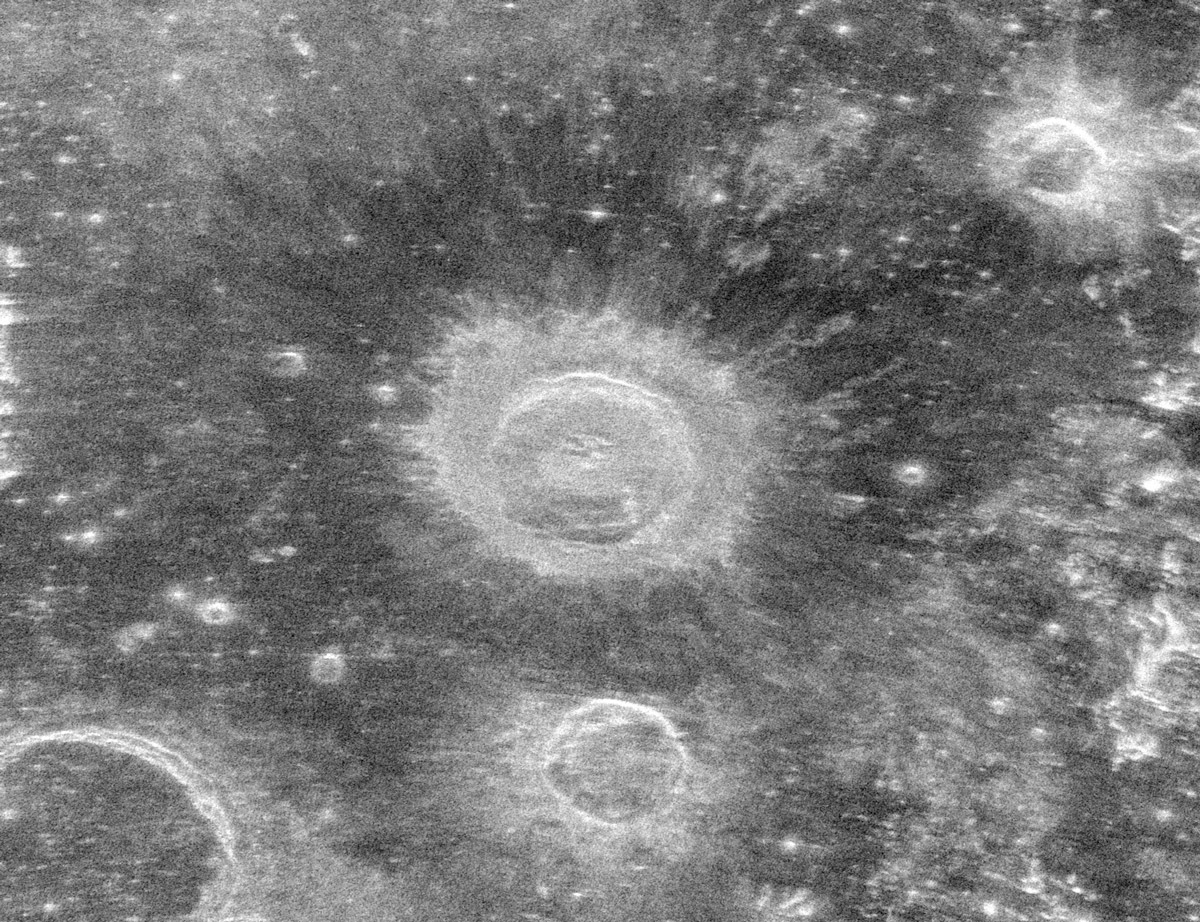

The radar images also provide a new perspective on Aristillus crater, which is about 34 miles (55 kilometers) wide and 2.2 miles (3.5 km) deep.

"The dark 'halo' surrounding the crater is due to pulverized debris beyond the rugged, radar-bright rim deposits," representatives of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, which operates the Green Bank Telescope and a number of other instruments, said in a statement.

"The image also shows traces of lava-like features produced when lunar rock melted from the heat of the impact," they added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Peering beneath the moon's dusty surface should help scientists better understand the history and evolution of Earth's natural satellite, researchers said. The new radar images could also improve knowledge about previous lunar landing sites and aid mission planners thinking about where to send future moon-exploration efforts, they added.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.