Full Moon of June a Delightful Boon for Stargazers

Over the next few nights, the full moon will be riding low in our summer sky.

The summer solstice will occur Saturday (June 21), so the noontime sun is nearly at the highest it can get in our Northern Hemisphere skies. This puts the full moon, occurring just after midnight Eastern Daylight Time on Friday the 13th, at close to the lowest it can possibly get this week.

The full moon is an instantaneous event: the exact instant when sun, Earth and moon fall closest to a straight line. A moment before this, the moon is in waxing gibbous phase; a moment after, it is in waning gibbous phase. Only at exactly 12:11 a.m. EDT (0411 GMT) is it exactly "full." [The Moon: 10 Surprising Facts]

As far as the naked eye is concerned, the moon looks full for a day or two on either side of the exact "full" phase. Only with a telescope can you see that the moon is being lit from a slight angle, causing the line of sunrise or sunset on the moon, called the terminator, to be very close to one edge or the other.

The result is that any night this week will look like a "full moon night."

An interesting event involving the moon occurred last week on Saturday (June 7). To viewers on Earth, it appeared as if the moon was very close to the planet Mars, what astronomers call a "conjunction." This was of course just an effect of perspective, Mars actually lying 320 million times farther away from us than the moon.

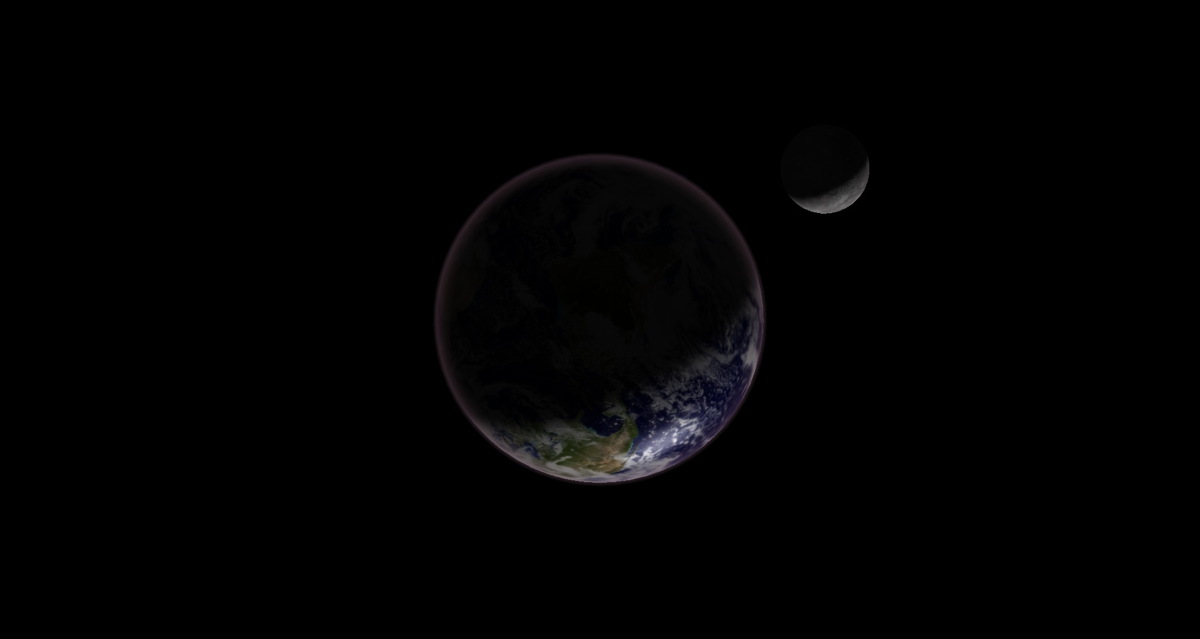

It's interesting to view this conjunction in the other direction, looking at the Earth and moon from the perspective of Mars, which can easily be done with stargazing software such as Starry Night. Our computer can transport us to the crater Dawes on the surface of Mars, named after 19th century British amateur astronomer William Dawes.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Looking back toward Earth, we would see Earth as a bright object in the dawn sky. The moon would appear so close to the Earth that it would require a telescope to see them as separate objects. To give you some idea of the scale of this view, the Earth would be 21 arc seconds in diameter, about half the diameter of Jupiter as seen from Earth. The moon would be 5.7 arc seconds in diameter, smaller than Mercury appears from Earth. The distance between them would by a mere 5 arc seconds.

If you were to take a closer look at the moon, you wouldn't recognize a single feature. That's because you would be looking at what we call "the far side" of the moon. Our moon, like all moons in the solar system, always keeps the same face inward. On June 7, the moon lay almost exactly between the Earth and Mars, so the face of the moon toward Mars would be the face of the moon we never see from Earth.

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing photo of the moon, or any other night sky view, and you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please send comments and images to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Nightand SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow Space.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.