Two spacecraft have detected a possible signal of dark matter, the mysterious, invisible stuff that makes up most of the material universe.

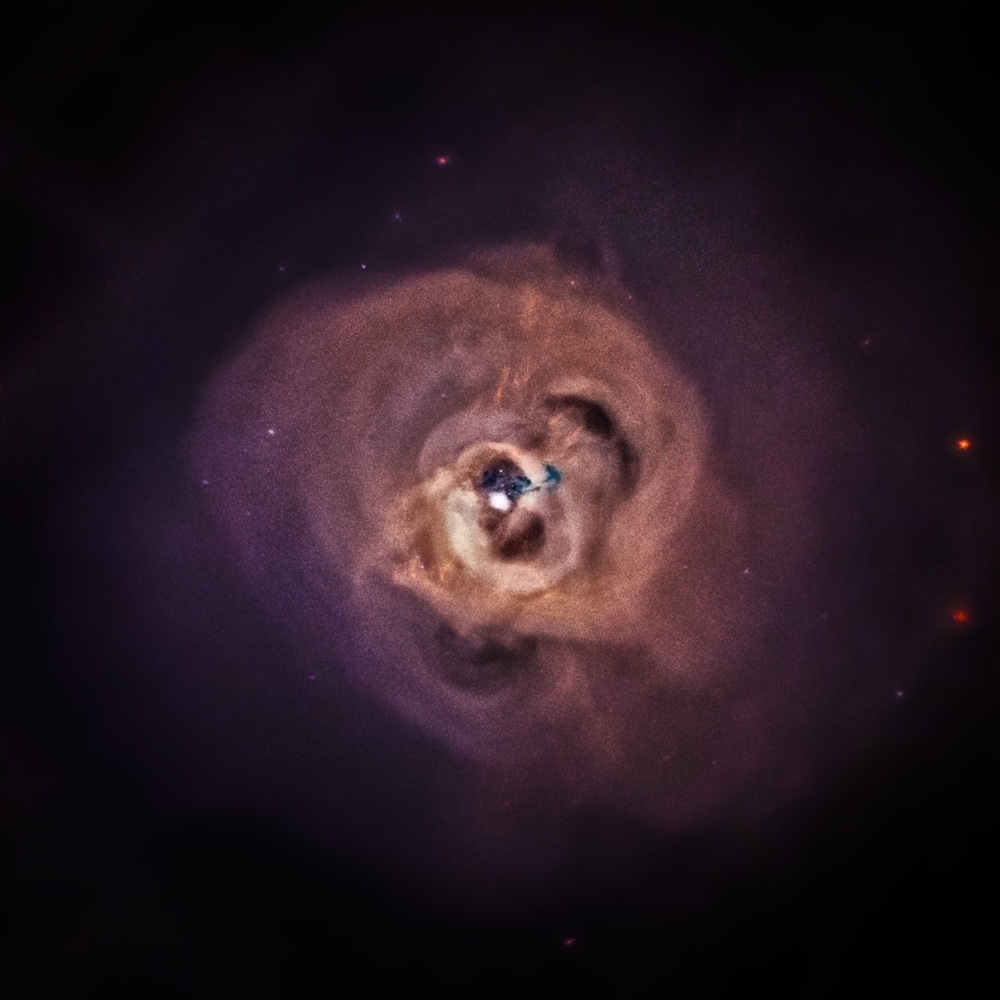

NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton satellite spotted a spike of X-ray emission coming from more than 70 different galaxy clusters. While the origin of the X-rays remains unclear at the moment, they could be generated by the decay of a certain type of dark-matter particle, scientists said.

"We know that the dark matter explanation is a long shot, but the payoff would be huge if we're right," study lead author Esra Bulbul, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, said in a statement. "So we're going to keep testing this interpretation and see where it takes us." [Gallery: Dark Matter Throughout the Universe]

Dark matter is so named because it neither absorbs nor emits light, making it impossible to observe directly. But astronomers know that dark matter exists because it interacts gravationally with the "normal" matter we can see and touch.

In fact, dark matter is thought to make up more than 80 percent of all matter in the universe. But scientists don't know exactly what it is.

Over the years, researchers have proposed a number of exotic particles as candidate components of dark matter, including weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs), axions and sterile neutrinos — a hypothetical type of neutrino that emits X-rays when it decays.

It's possible that the signal observed by Chandra and XMM-Newton was produced by sterile neutrinos, researchers said. But that's far from a sure thing, they stressed, since the detection of the X-ray spike pushed both observatories to their sensitivity limits.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We have a lot of work to do before we can claim, with any confidence, that we've found sterile neutrinos," co-author Maxim Markevitch, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in a statement. "But just the possibility of finding them has us very excited."

"Normal" matter in the galaxy clusters may also be responsible for the emission (if it is indeed real and not an instrument artifact). But this interpretation doesn't mesh well with current thinking about galaxy clusters and the atomic physics of hot gases, researchers said.

"Our next step is to combine data from Chandra and JAXA's [the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency's] Suzaku mission for a large number of galaxy clusters to see if we find the same X-ray signal," said co-author Adam Foster, also of CfA.

"There are lots of ideas out there about what these data could represent," Foster added. "We may not know for certain until Astro-H launches, with a new type of X-ray detector that will be able to measure the line with more precision than currently possible."

Astro-H is an X-ray observatory being developed by JAXA. It's scheduled to be launched to Earth orbit next year.

The new paper was published in the June 20 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.