NASA Urged to Accelerate 3D Printing on Space Station

NASA must move quickly to research 3D printing aboard the International Space Station, which likely has just six to 10 years of operational life left, a new report urges.

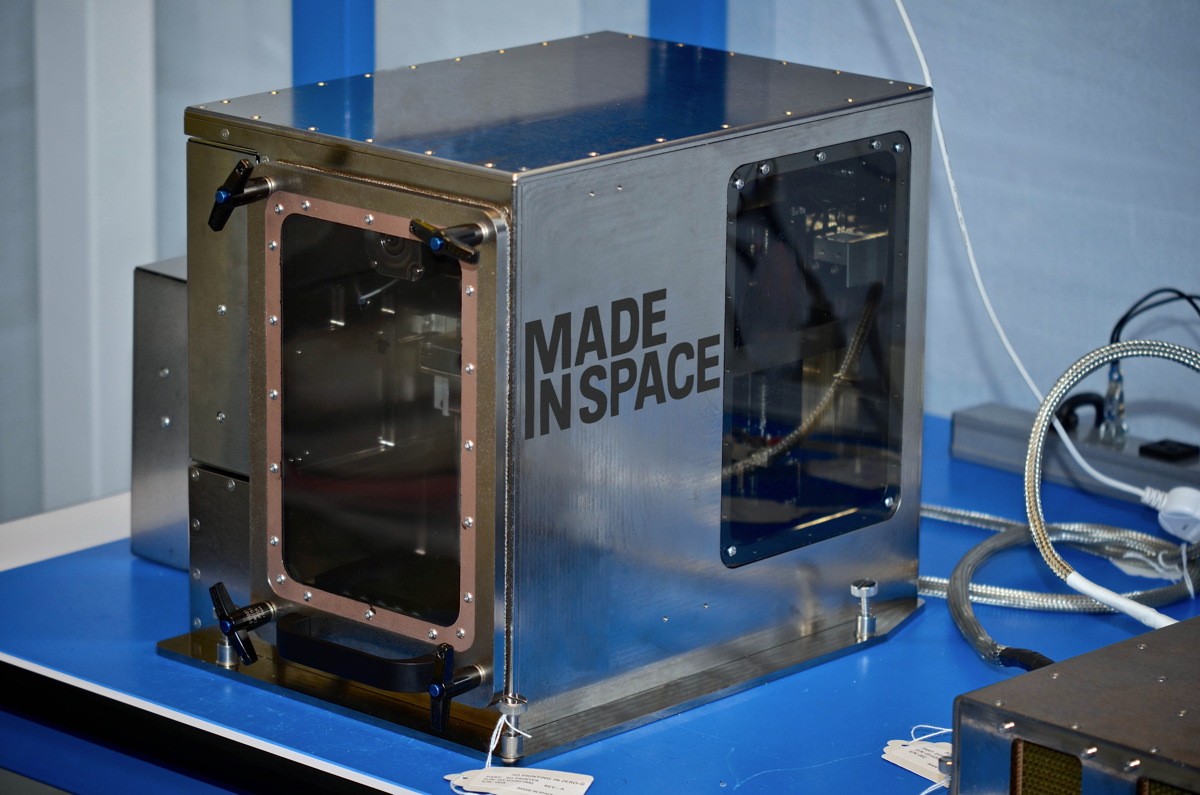

While praising NASA's efforts and focus on in-space manufacturing — a 3D printeris scheduled to launch to the station next month, for example — the U.S. National Research Council (NRC) report stressed that the agency should organize its various centers to identify priority projects for use on the station.

"The ISS isn't going to be around forever, and it's the one place where we can actually do [in-space] experimentation," Robert Latiff, a retired U.S. Air Force major general with a Ph.D. in metallurgical engineering and materials science, told Space.com. Latiff chaired the committee that wrote the NRC report, which was released July 18. [10 Ways 3D Printing Could Transform Space Travel]

At 3D printing's current state of development, it makes sense to have humans supervising the process to make sure it is meeting standards, Latiff said. This could present a challenge for the tightly scheduled astronauts, he added.

"They measure their times down to the minute," Latiff said.

But the report noted that the station provides a good opportunity to learn more about how 3D printing works in microgravity. And if the process were performed outside of the station, it would teach researchers how thermal stresses — quick changes from hot to cold, for example — could affect the materials.

The United States recently proposed that International Space Station operations be extended to 2024 from 2020, but that request hasn't yet been approved by all other partners in the project.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Not a panacea

A lot of hype surrounds 3D printers these days, with many news reports saying the machines can produce parts that are lighter, stronger and more advanced than those made using traditional manufacturing techniques. For example, Latiff said, it's possible for a single component to have different properties along its length, or to put together parts that don't have traditional connectors.

But the use of 3D printing in space requires a strong understanding of materials science to make it work. NASA has been doing experiments in this area since the Skylab space station of the 1970s, Latiff said. He urged tighter integration between scientists and manufacturers as they seek other uses of 3D technology.

3D printing is still in its infancy, especially when it comes to manufacturing "thinking" materials such as semiconductors, the report said. Printing today is more focused on making prefabricated components and "primitive" electronics such as conductors.

"You can build a part, but it isn't altogether clear that a 3D-manufactured part is going to be necessarily as good [as a part] that was built some other way," Latiff said. "And there are things we talk about in the report that we haven't even begun to understand, like certification."

A year in the making

Printing on the space station isn't the only thing being considered. The European Space Agency has spoken about someday doing 3D printing of lunar base components, such as human habitats. NASA is also funding a company called Tethers Unlimited, which hopes to launch very small materials (such as thread spools) that would transform into kilometer-long antennas or solar arrays in space.

Within the United States, the Air Force plans to use 3D printing on the ground to manufacture lighter parts for rockets and satellites, to reduce the amount of fuel needed to lift things into space. But most of the Air Force's experience so far is focusing on aerospace and not space parts, Latiff said. The report urges the Air Force and NASA to talk more closely and share expertise.

Committee members spent more than a year examining the state of the industry before publishing their report, called "3D Printing In Space." Four or five meetings were held, most of them open to the public, with experts from NASA, the Air Force, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and other organizations attending.

Committee members included a mix of experts from U.S. laboratories, universities and military agencies. One member, Sandy Magnus, is a former space shuttle and space station astronaut. The report was examined by a second committee of experts, who marked it up with comments that had to be addressed before publication, Latiff said.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.