UK to Launch Commercial Spaceport by 2018

The U.K. government is laying the groundwork for its first spaceport in anticipation of a growing space tourism demand and a growing space plane industry by 2030, according to a new timetable. Government officials also envision orbital launches from that country within the next 15 years.

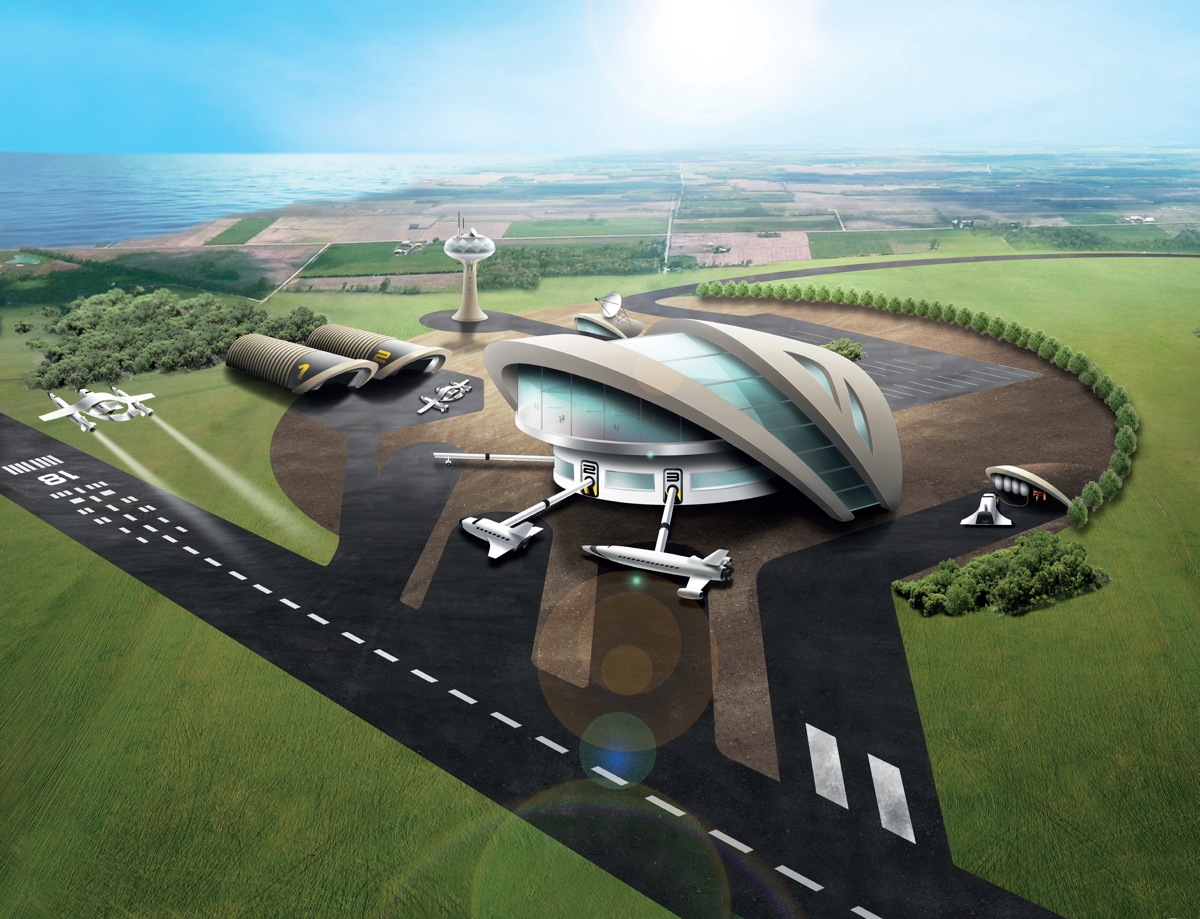

According to the new timetable, unveiled at the Farnborough International Airshow last month, the U.K. is planning to build $85.5 million spaceport (50 million British pounds) and anticipates a space tourism market worth $65 million each year, as well as a space plane industry worth $33.9 billion (20 billion pounds) by 2030.

The timetable lays out a number of other specific dates: The spaceport could be operational from 2016; the first suborbital flight would occur in 2018; the first sub-orbital space plane satellite launch from the spaceport would take place in 2020; rocket engine testing for the orbital space plane would occur in 2026, and that space plane would be operational four years later. [Evolution of the Space Plane (Infographic)]

The rocket-engine testing refers to hybrid engines, which are used by the Skylon space plane, manufactured by U.K. company Reaction Engines.

A British spaceport

U.K. Space Agency Director General David Parker published the timetable at the Farnborough International Airshow's Space Day Conference on July 15. He also signed a memorandum of cooperation for space plane operations with the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Associate Administrator for Commercial Space Transportation George Nield, and announced that Lockheed Martin will open a space technology office in the English town of Harwell in Oxfordshire.

Choosing a spaceport site

From now until October this year, the U.K. Space Agency is undertaking a public consultation about possible spaceport sites. Selection of a site could take place before the end of 2016. The U.K. Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) has identified eight sites across the United Kingdom's nations of England, Scotland and Wales after 18 months of work. Six of the sites are in Scotland, one is in Wales, and the one site in England is on the country's southern coast, at Newquay Cornwall Airport. Newquay is known in the United Kingdom for its surfing.

Andrew Nelson, chief operating officer and vice president of business development of Mojave, California-based space plane developer XCOR Aerospace, spoke to Space.com at the Airshow about his company's interest in one proposed site, Newquay. "Newquay is sort of interesting. It points right out to the water. You're not flying over anything under rocket power, which is nice." U.K. government officials interviewed Nelson and other XCOR staff in June and early July 2013 at Mojave, spending two to three days there, Nelson said. The officials also spoke to Virgin Galactic and Stu Witt, manager of the Mojave Air and Space Port. [See an animation of the Lynx in flight]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Previously, potential users, such as Virgin Galactic, have favored Lossiemouth, in Scotland. A 2009 report into spaceport candidate locations for the U.K. Space Agency's predecessor, the British National Space Centre (BNSC), found Lossiemouth to be the best site. Located in northern Scotland, Lossiemouth is on the coast of the North Sea and has a Royal Air Force base with a runway suitable for the types of launch systems used by Sir Richard Branson's Virgin Galactic. That company had already identified Lossiemouth as a possible U.K. spaceport; in 2009, then Virgin Galactic President Will Whitehorn, who was born in Scotland, spoke of his hope for a spaceport in the location. The 2009 report did not set a date for constructing such a facility.

A September referendum on whether Scotland will remain a part of the United Kingdom could complicate that choice for a 2018 spaceport, however. If the yes vote in the referendum wins, Scotland could be an independent country by 2018. A poll last week by ICM Research found that 34 percent of Scottish voters would vote yes for independence, 45 percent would vote no and the remainder don't know.

The $85.5 million spaceport price tag comes from a science report published in April by the U.K. Space Agency's parent body, the Government’s Department for Business, Innovations and Skills (BIS). Parker told Space.com that the cost estimate for the spaceport was an informed guess. The BIS report also proposed a national space propulsion facility that would cost about $10 million, or 6 million British pounds.

The eight spaceport sites and the detailed timetable published at the Farnborough Space Day Conference come from the CAA's report, "U.K. Government Review of Commercial Space Plane Certification and Operations," released this month. The report’s timetable also envisages a number of other goals: wet lease agreements by 2016 under common FAA and CAA rules, pan-European space plane legislation regulation developed from 2016 and a vertical rocket launch site to be identified in northern Scotland by 2020. And from 2020 to 2030, the CAA expects space planes to be certified and no longer experimental, space plane operations to start from additional sites in the United Kingdom, and most U.K. spaceflights to use U.K. crews.

Whichever spaceport is selected, Xcor and Virgin Galactic are the most likely space plane developers to be in a position to launch from the spaceport in 2018. The report also identifies several other spaceport users: Airbus' Spaceplane, Bristol Spaceplanes' Spacecab, Orbital Sciences' Pegasus rocket, Stratolaunch Systems' air-launched system and Swiss Space Systems' Sub-Orbital Aircraft Reusable vehicle. [See photos of Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo]

Market research by the U.K. small satellite maker Surrey Satellite Technology (SSTL) calculated that the first year of space tourism operations would have 120 tourists with 150 tourists in year three. This assumed Xcor and Virgin Galactic were operating in the United Kingdom. It would mean revenue of $24 million by that year three, SSTL said. By year 10, SSTL expects more than 400 tourists and annual revenues of $65 million.

Red-tape barriers

Despite the United Kingdom-focused timeline, Xcor and Virgin employ U.S. rocket technology. The use of that technology outside of the United States is regulated under export controls. Called International Traffic in Arms Regulations or ITAR, it is the first obstacle to operating rocket-powered space planes outside of the United States. The U.K. Ministry of Defence has made progress on understanding this issue, said U.K. Space Agency Director for Growth, Applications and European Union Programs Catherine Mealing-Jones, speaking at the Space Day Conference.

Another regulatory issue is the legal process to allow the space planes to fly in U.K. airspace up to space. Under the Outer Space Treaty that the United Kingdom signed, governments are responsible for launches by their citizens. The U.K. Space Agency is the regulatory authority for the U.K. Outer Space Act 1986, and discharges the country's obligations under the four outer-space-related treaties. However, Parker told Space.com that because suborbital space planes do not go into orbit, the treaty does not apply. Instead, Parker's agency plans to treat space planes as experimental aircraft under U.K. and European aviation law. Passengers would have to agree to something like the informed consent concept that the FAA is using.

However, the report also states that the United Kingdom should not adopt the FAA approach and instead should remain in step with "future [European Union] developments." The European Union (EU) could have space plane legislation within the next five years. The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) is an EU agency, and the United Kingdom is a member state of EASA. The EASA official drawing up the space plane legislation, Jean-Bruno Marciacq, told Space.com at the Space Day Conference that the legislative proposals are ready to go the European Commission's (EC) Department of Mobility and Transport.

The delay has been due to the EU's European Parliament elections, held every five years.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rob Coppinger is a veteran aerospace writer whose work has appeared in Flight International, on the BBC, in The Engineer, Live Science, the Aviation Week Network and other publications. He has covered a wide range of subjects from aviation and aerospace technology to space exploration, information technology and engineering. In September 2021, Rob became the editor of SpaceFlight Magazine, a publication by the British Interplanetary Society. He is based in France. You can follow Rob's latest space project via Twitter.