Cosmic Quest: Who Really Discovered Neptune?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Neptune will appear directly opposite the sun in the sky tomorrow (Aug. 29), but despite the potentially clear view of the planet from Earth, the truth about the person who first discovered the distant world remains cloudy.

Neptune was supposedly discovered in 1846 by Johann Gottfried Galle using calculations by Urbain Le Verrier and John Couch Adams, making it a joint British-French-German discovery.

But these astronomers were not the first to observe Neptune. That honor goes to the famous Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei.

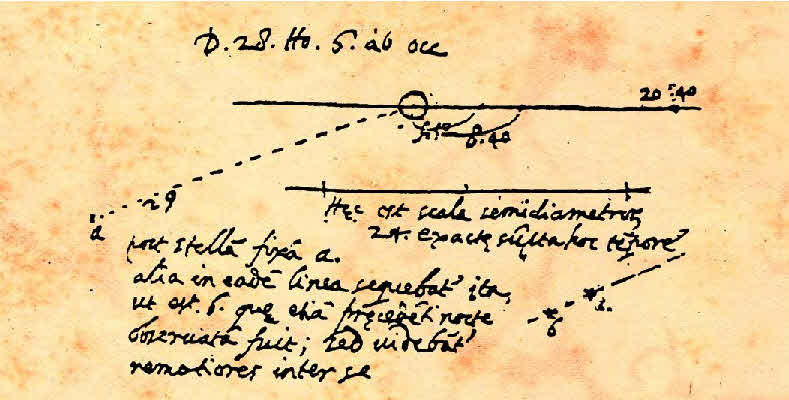

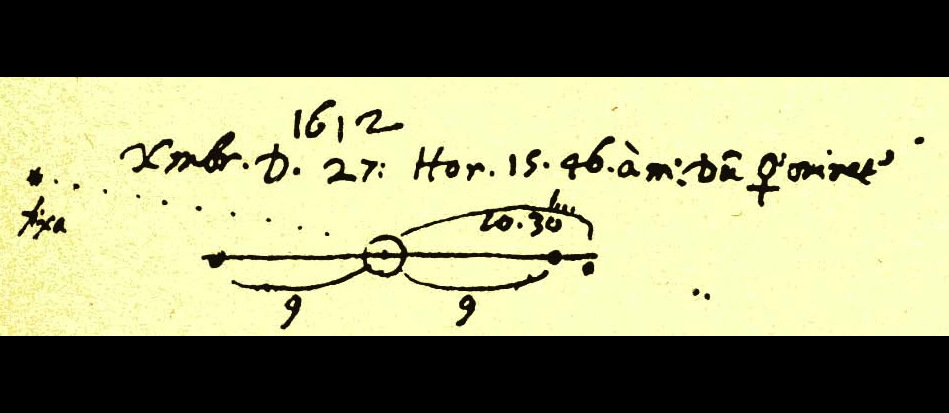

While sketching the moons of Jupiter with his newly discovered telescope, Galileo twice drew Neptune, which happened to be in conjunction with Jupiter in early 1613. It’s usually said that Galileo mistook Neptune for a star because of its slow movement. [See amazing images of Neptune]

David Jamieson of the University of Melbourne argued recently that Galileo did indeed see Neptune move and realized it was a planet. Jamieson thinks Galileo announced this in an anagram, but it was suppressed by the Catholic Church.

It’s interesting to examine historic observations like Galileo's to see what was actually observed. Modern planetarium programs allow us to do this.

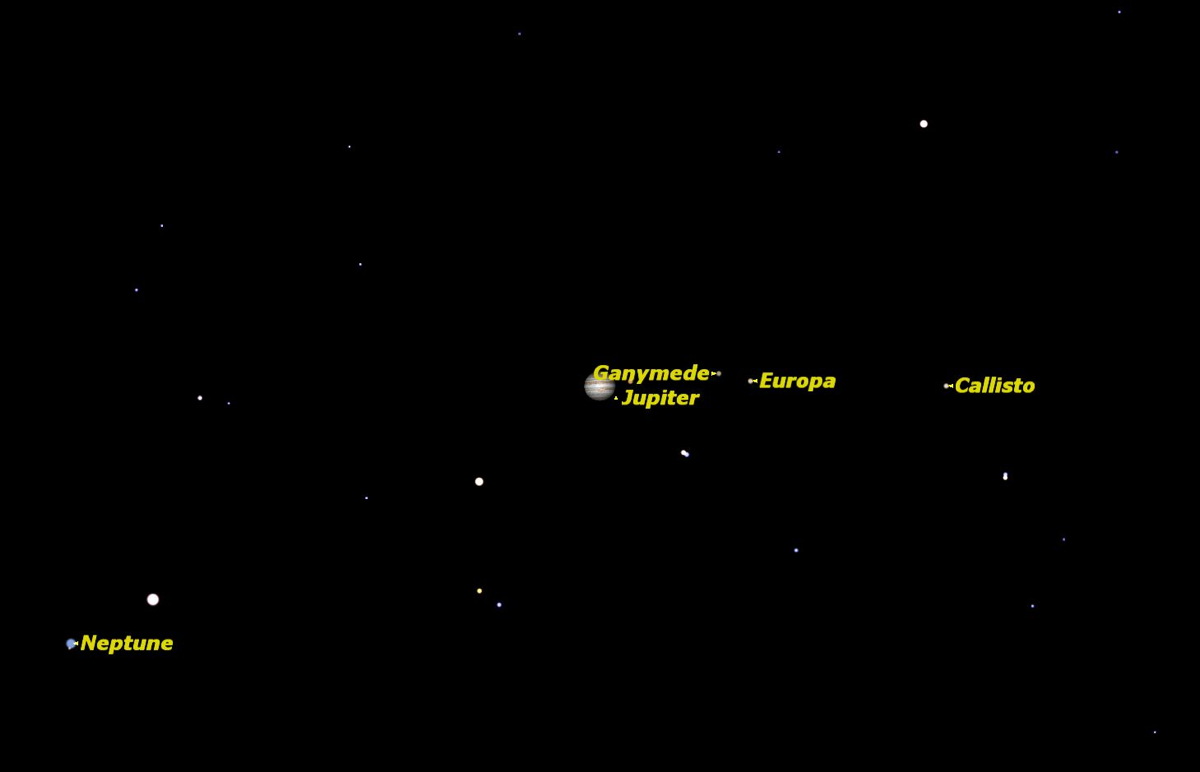

By using Starry Night software, observers can re-create views of the night sky that Galileo saw in the 1600s. Galileo's sketch from Dec. 27 or 28, 1612 shows Jupiter framed by its moons Ganymede on the left and Europa on the right, with Callisto a little further to the right. Neptune is on the left, and slightly north of Jupiter.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Just over a month later, Galileo sketched the moons again. All four moons are off to Jupiter’s right, and Galileo has portrayed their positions accurately, based on the Starry Night rendering of his sky. Neptune is again to Jupiter’s left, but now south of Jupiter.

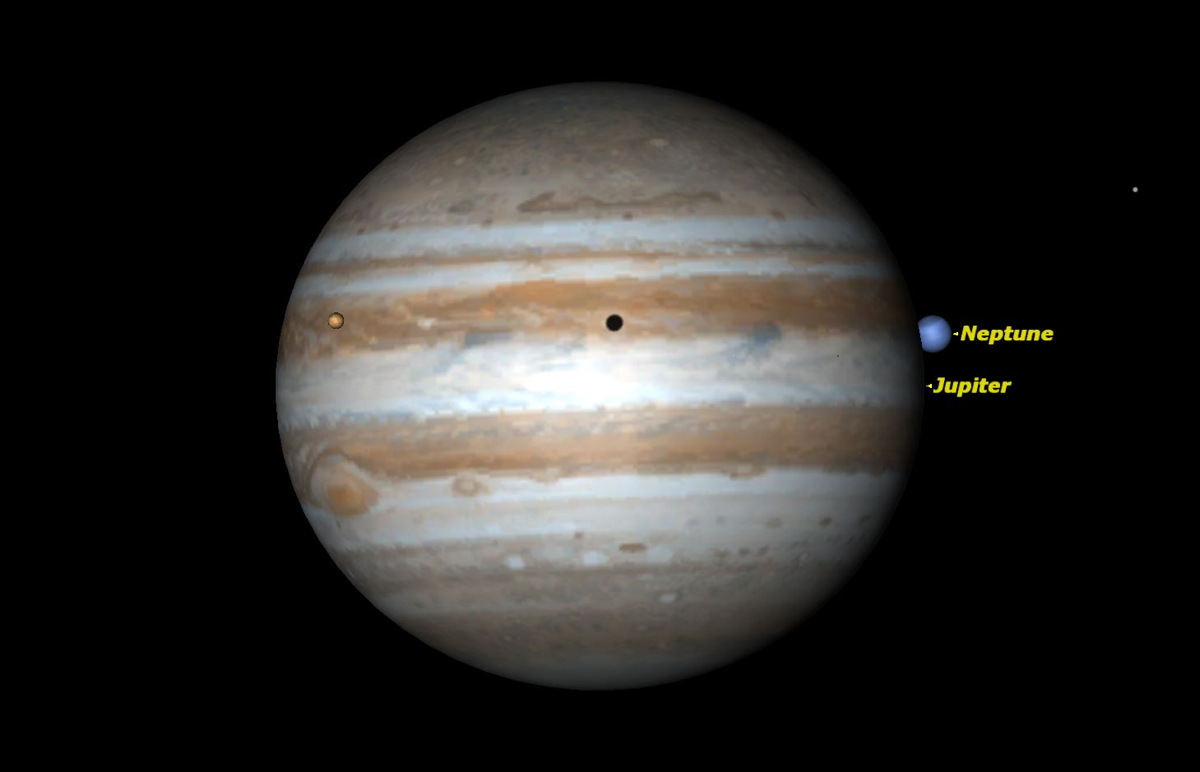

What happened between these two sketches is truly remarkable. When the first sketch was made, Neptune was moving from left to right relative to Jupiter. On January 3 or 4, 1613, Neptune actually passed behind Jupiter, an extremely rare planetary occultation. If Galileo took out his telescope just before dawn on the morning of Jan. 4, he would have seen Neptune emerging from behind the dark limb of Jupiter.

Neptune was stationary relative to Jupiter on January 13, and then started moving from right to left, passing Jupiter again on Jan. 23, 1613. The planet again ended up on the left of Jupiter for Galileo’s second observation on Jan. 28 or 29.

Galileo’s primitive telescope was capable of only about 30 times magnification. Neptune would have looked to him like a star, just as it does in small telescopes today. It takes a very large telescope, and very good conditions to see anything like the view in Starry Night. Even through the largest telescope in Canada — the 74-inch reflector at the David Dunlap Observatory north of Toronto — Neptune appears as a featureless blue disk.

You can see the opposition of Neptune on Friday night in a webcast hosted by the Slooh Community Observatory. You can watch the Neptune webcast on Space.com on Aug. 29 starting at 8 p.m. EDT (0000 Aug. 30 GMT) via Slooh.

This article was provided to Space.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.