Mars Probes from US and India Arrive at Red Planet This Month

The planet Mars is about to have some company. Two new spacecraft, one from the United States and the other from India, are closing in on the Red Planet and poised to begin orbiting Mars by the end of this month.

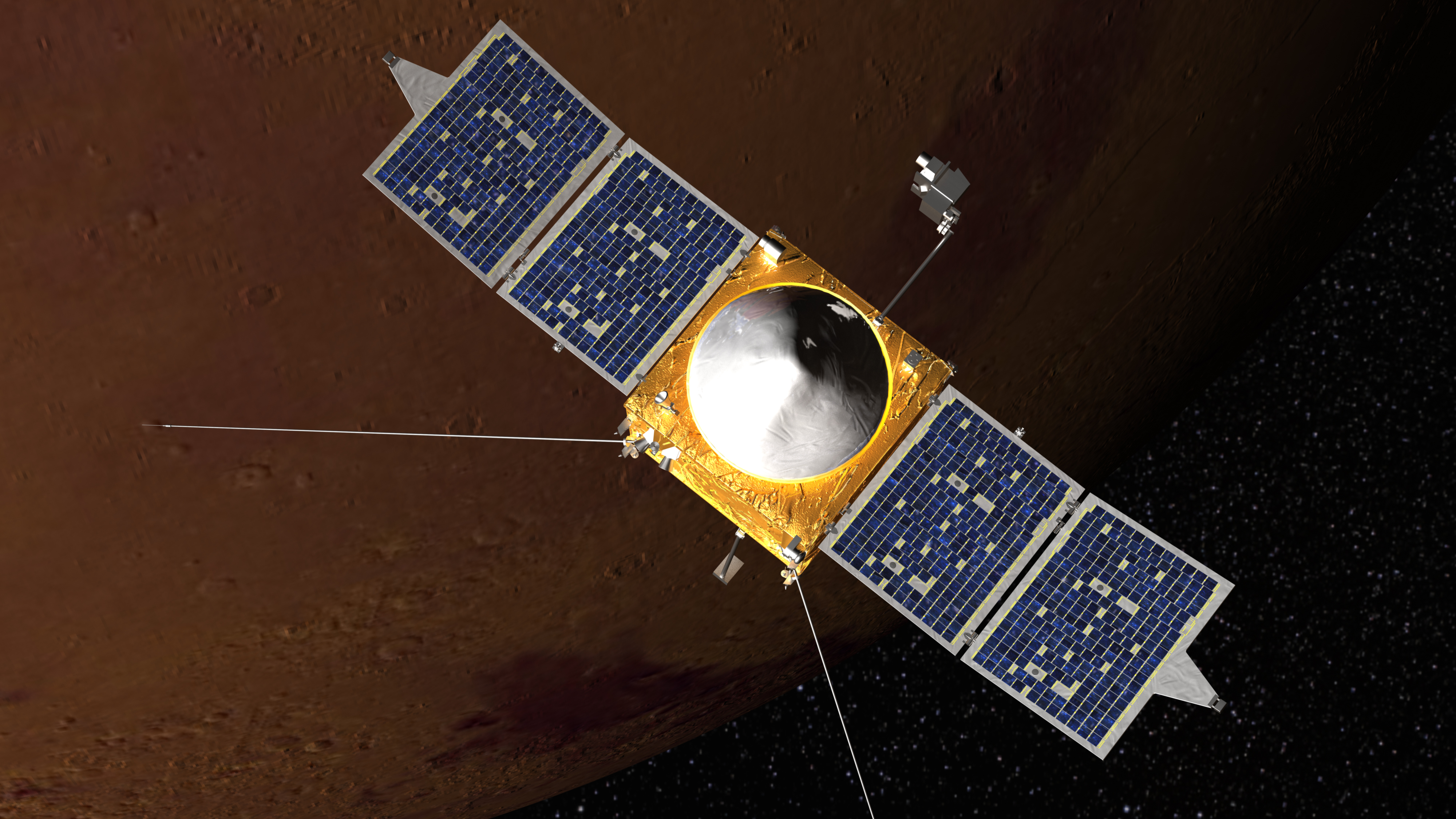

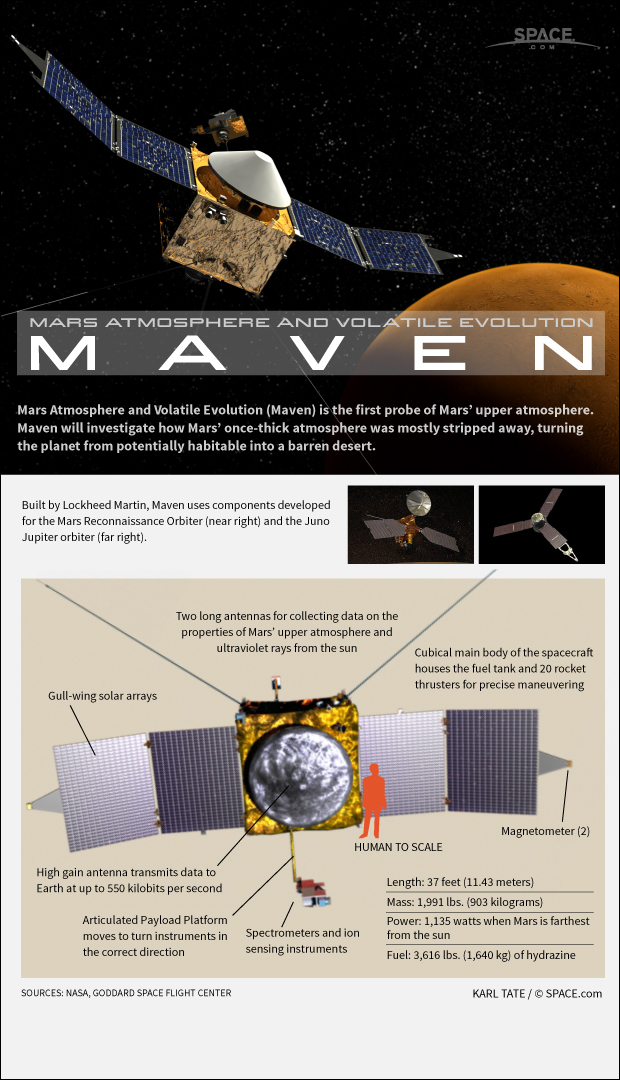

The U.S.-built probe, NASA's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) spacecraft, is expected to enter orbit around Mars on Sept. 21. Just days later, on Sept. 24, India's Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) orbiter is due to make its own Mars arrival when it enters orbit. Both MOM and MAVEN launched to space in 2013.

MAVEN is the first mission devoted to probing the Martian atmosphere, particularly to understand how it has changed during the planet's history. [See images from the MAVEN mission]

Before that happens, however, the spacecraft must burn its engines to go into orbit around the planet, and pass a commissioning phase while taking a few precautions for a "low-risk" situation where a comet will pass fairly close to Mars.

"We've been developing MAVEN for about 11 years, and it comes down to a 33-minute rocket burn on Sept. 21," MAVEN principal investigator Bruce Jakosky, of the University of Colorado, Boulder, told Space.com.

The spacecraft can change tracks as late as 6 hours before entering orbit, but right now, it is so close to the correct path that a planned orbital maneuver on Sept. 12 won't be needed, Jakosky said.

Comet Siding Spring will pass near Mars on Oct. 19, and around that time, MAVEN will take a break from its commissioning to do observations of the comet and the planet's upper atmosphere. Although not much dust is predicted to result from the event, as a precaution, controllers will turn off nonessential instruments and move the solar panels edge-on to the dust. The spacecraft will also be behind Mars for 20 minutes during the comet's closest approach.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Where did Mars' atmosphere go?

One of MAVEN's primary scientific tasks will be to figure out how the Martian atmosphere changed during the planet's 4.5-billion-year history.

Several NASA spacecraft have found extensive evidence that water once flowed on the planet. For water to have flowed on Mars, the planet would have required a thicker atmosphere. But why and how the atmosphere got thinner, to the way it is now, is one question that puzzles scientists.

MAVEN is expected to last at least one Earth year, but with careful use of fuel, it could last a decade — long enough for controllers to watch the upper atmosphere change through almost an entire 11-year cycle of solar activity.

Most of Mars' water disappeared about 3.5 billion years ago, Jakosky said, and there will be two approaches for MAVEN to figure out how the atmosphere played into that.

One approach will be to look at the atmosphere today and try to extrapolate its changes to what it used to be billions of years ago. However, one complication of that approach is that the sun's output has changed over time. Early in the solar system's history, the sun's total output was 30 percent less than it is today. Therefore, Earth and Mars could have been colder, but the solar wind and ultraviolet energy would have been more intense.

The second approach will be to look at the ratio of stable isotopes (element types) in the atmosphere, specifically the ratio of hydrogen to its heavier cousin, deuterium. Over time, the sun pushes lighter elements out of the atmosphere, leaving the heavier ones behind.

Scientists already have gained a pretty firm understanding of the past deuterium-hydrogen ratio by examining known Martian meteorites and older Martian minerals that NASA rovers probed on the surface, Jakosky said. The next step will be to get more information on today's conditions, to make comparisons.

"It's a powerful way to determine the history of the atmosphere," he said. "We're hoping that will be one of the early results coming out of MAVEN."

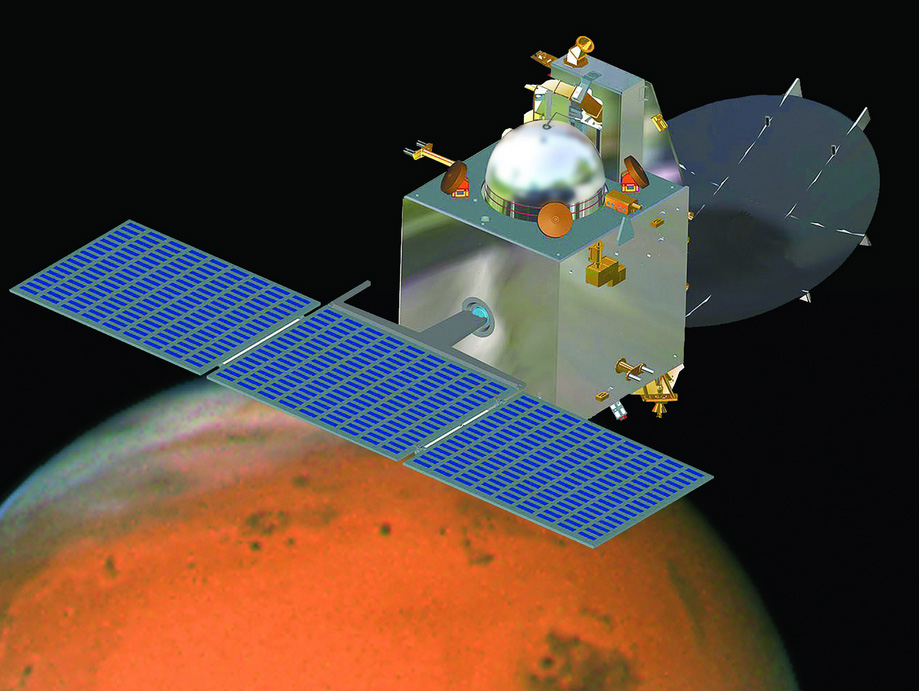

India's Mars MOM on NASA's heels

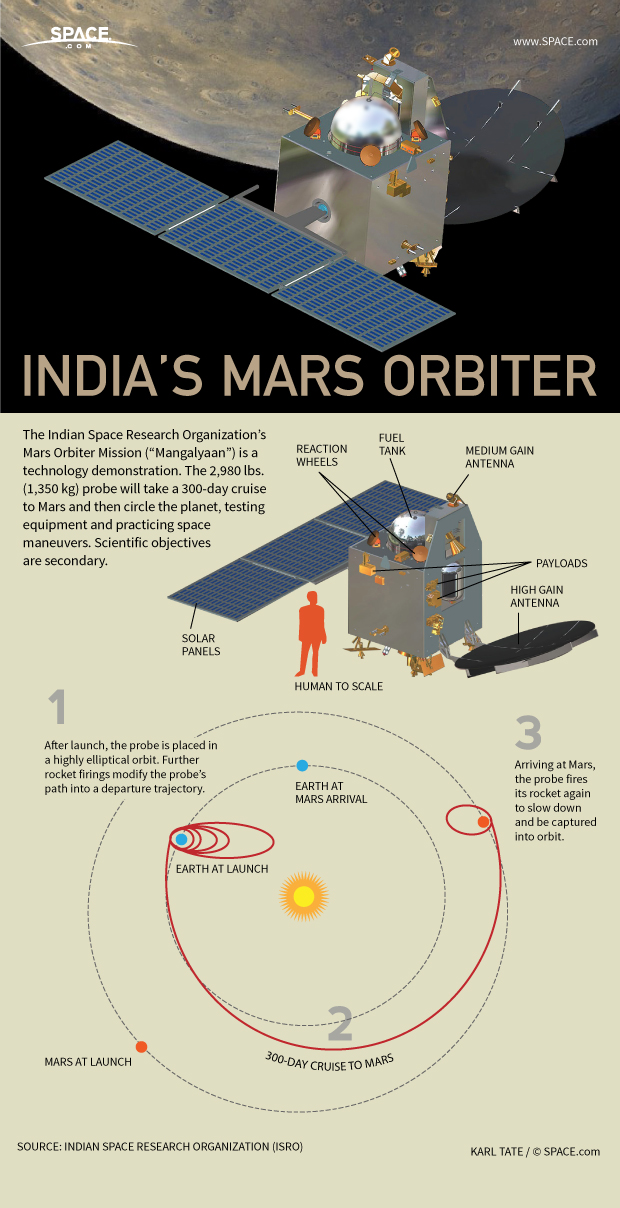

The Indian Space Research Organization's Mars Orbiter Mission is India's first mission to Mars and is designed to search for elusive methane in Mars' atmosphere from orbit. Over the years, different orbital and surface missions have found variable amounts of the gas, which can be produced by nonbiological or biological means.

MOM is expected to last six to 10 months near Mars, and has five instruments on board. The spacecraft and all of its payloads are in good health, ISRO said in a Facebook update on Aug. 30.

One of the mission's greatest challenges will be to fire the liquid propulsion engine after it sat idle for nearly 300 days in space. The engine is required to bring the spacecraft into Mars' orbit. Media reports indicate that India plans to do a test fire of the engine on Sept. 22.

If the Indian space agency is successful in reaching Mars, it will be the fourth entity to have done so, following the Soviet Union, the United States and the European Space Agency.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.