Black Hole Gas Guzzler May Explain Weird Superbright X-rays

A black hole is eating a star faster than scientists had thought was possible, and it's unleashing unusually bright X-ray signals that may help scientists understand a group of weird, superbright objects in deep space.

The discovery helps shed light on the origin of so-called ultraluminous X-ray sources, and also suggests that black holes can grow faster than previously thought, researchers say.

In the late 1970s, astronomers discovered sources of unusually bright X-rays blazing in deep space. It was long uncertain what these ultraluminous X-ray sources were. Scientists thought black holes powered these mysteries, with the matter around them giving off light as the black holes ripped it apart, but they disagreed about what the black holes' masses might be. [The Strangest Black Holes in Space]

Black hole (former) sun

Most black holes are created during the violent deaths of giant stars. These stellar-mass black holes weigh about three to 100 times the mass of the sun. On the other end of the size range are supermassive black holes that are millions to billions of times the mass of the sun,and lurk in the centers of galaxies.

Ultraluminous X-ray sources have a brightness in between that of stellar-mass and supermassive black holes. As such, researchers suggested that these ultraluminous X-ray sources might involve intermediate-mass black holes that are hundreds to thousands of times the mass of the sun.

However, scientists have now identified one ultraluminous X-ray source, and it turns out not to be an intermediate-mass black hole, but rather an unusually bright stellar-mass black hole no more than 15 times the mass of the sun.

"Black holes with relatively modest masses may find ways to radiate huge X-ray luminosities," lead study author Christian Motch, an astronomer at the University of Strasbourg in France, told Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Small black hole, fast eater

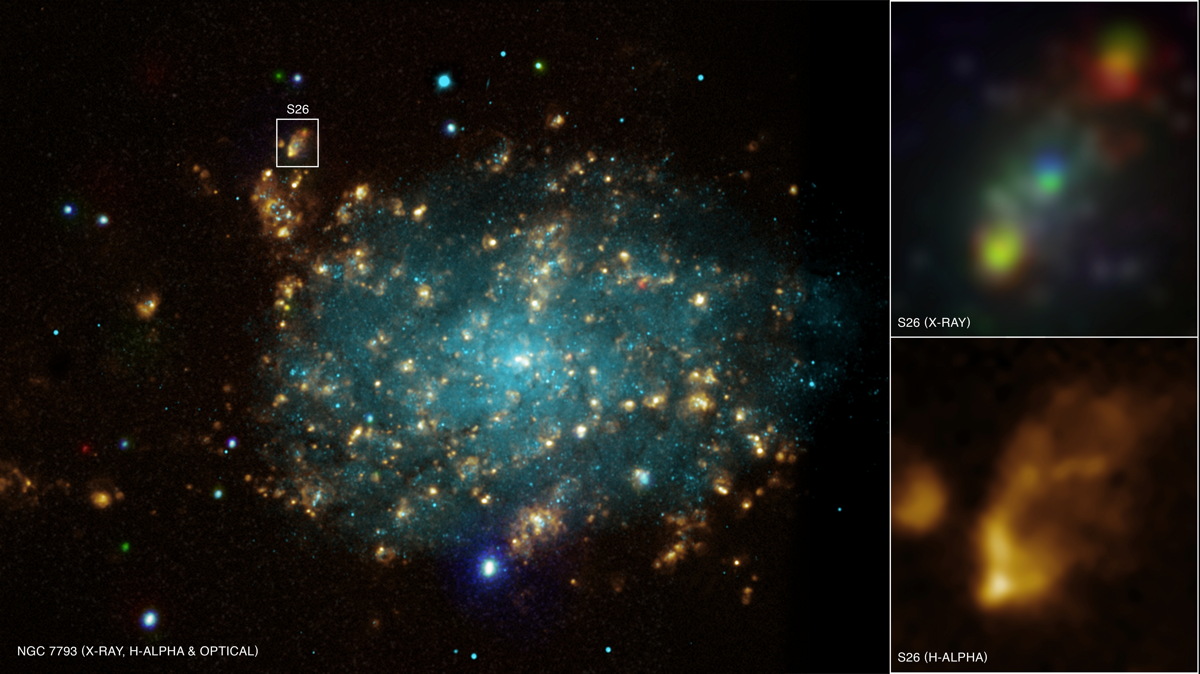

The discovery in question is a black hole labeled P13 in the outskirts of the nearby spiral galaxy NGC 7793, about 12 million light-years away. This black hole, by far the brightest X-ray source in its galaxy, was discovered more than 30 years ago by NASA's Einstein X-ray telescope.

The black hole possesses a companion star, a kind of blue supergiant 18 to 23 times the mass of the sun. As gas from this companion gets sucked into P13, this matter becomes very hot and bright, making the black hole at least a million times brighter than the sun.

The astronomers gazed at the black hole and its companion with a combination of optical and X-ray telescopes over the course of eight years — the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile, as well as the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton and NASA's Chandra and Swift X-ray observatories in space. The researchers determined that the black hole and its companion star complete a very oval-shaped orbit around each other every 64 days.

When the black hole approaches the star, the X-rays from it heat up and brighten the side of the star facing the black hole. By carefully modeling this effect, the astronomers were able to estimate the black hole's mass.

Voracious appetite

The amount of light the black hole gives off suggests it gorges on gas at an exceptional rate — the equivalent of the mass of the moon every three weeks, or the mass of Earth every four years. This is significantly greater than a theoretical maximum known as the Eddington limit, which is the point at which the energy given off by matter rushing toward a black hole should curb the amount of matter feeding that black hole.

Increasingly, research suggests black holes can overcome the Eddington limit. These so-called super-Eddingtongrowth rates could have a number of different explanations — for instance, radiation that might normally help push matter away from the black hole could get absorbed by matter falling into the black hole, Motch said.

These new findings suggest that stellar-mass black holes growing at super-Eddington rates could help explain "a majority of ultraluminous sources," Motch said. However, some ultraluminous X-ray sources are too bright to be stellar-mass black holes, even assuming super-Eddington rates of growth, or the wavelengths of X-rays they give off are consistent with growth rates below the Eddington limit. These other ultraluminous X-ray sources "may be powered by high-mass stellar black holes up to 100 solar masses, or by intermediate-mass black holes," Motch said.

The black hole discovery is detailed in the Oct. 9 edition of the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us