Leaky Galaxy Mimics First Light in Early Universe

A densely packed star-forming galaxy is reproducing the events that brought light to the early universe.

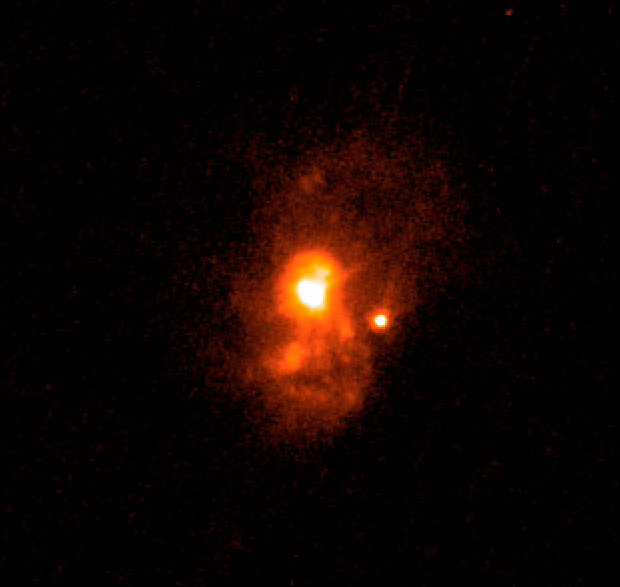

The nearby compact galaxy named J0921+4509, which is rapidly producing stars, has many of the characteristics that would have been required to light up the early universe. Located approximately 3 billion light-years from the Milky Way, the star-forming regions of the tightly bound galaxy are surrounded by dense clouds of gas. Holes in the gas allow radiation to leak out, mimicking events that would have broken through the darkness that followed the birth of the universe.

J0921+4509 produces approximately 50 solar-masses' worth of stars each year, more than 33 times the number of stars created by the Milky Way every year. While most stars in other locations remain swathed in the gas that forms them, trapping radiation inside, J0921 has holes that allow the radiation to escape, much as it might have in the early universe. [The History and Structure of the Universe (Gallery)]

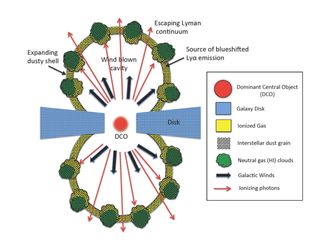

"The high density of stars in a compact region in J0921+4509 results in an explosion-like feedback that is able to create the gaps," lead author of the study Sanchayeeta Borthakur, of Johns Hopkins University, told Space.com by email.

Leaking galaxies

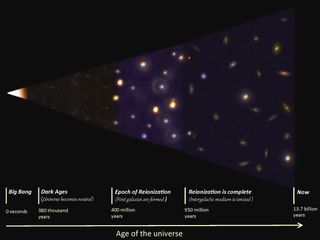

Only a few hundred thousand years after the Big Bang, hydrogen gas in the universe cooledand became neutral as protons and electrons paired up. Any radiation emitted was quickly absorbed, rendering the period unobservable, or "dark," to astronomers. By the end of the first billion years, radiation known as Lyman continuum had reionized the hydrogen, scattering electrons and making the universe visible once again.

Events from the dark agesof the universe, including its reionization, cannot be directly studied. Instead, astronomers must search for similar processes in objects they can examine today, such as those found in the starburst galaxy J0921. The name "starburst galaxies" comes from the unusually high rate of stellar production in such locations; J0921 produces greater than 33 times more stars than the Milky Way.

Most of the radiation that broke electrons from the neutral hydrogen during the reionization period is thought to come fromstellar births. Stars form deep inside cold, dense clouds, where temperatures drop as low as minus 262 degrees Celsius (minus 440 degrees Fahrenheit). These stars emit radiation, but it is quickly absorbed by the cloud of gas around the stars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In J0921, however, the stars lay so close together — the galaxy is just over 650 light-years across — that radiation and rapid heating from the winds flowing from the stars out of the galaxy widen existing small holes, allowing the ionizing radiation to escape. Borthakur and her team captured the leaks with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. In the early universe, escaping radiation like this could have served to energize particles, breaking up the neutral hydrogen that dampened visibility.

A starburst studied

A handful of galaxies in the early universeare leaking radiation. Scientists are able to study these galaxies from the universe’s youth because of the correlation between the distance light travels and the time it takes to make the journey. Essentially, looking at objects in the distant universe is like looking back in time; astronomers see the light as it was when it left the object.

Galaxies in the early universe lie nearly 13 billion light-years from the Milky Way, which makes studying them a challenge. J0921, in contrast, lies about 3 billion light-years away, making it far easier to gain a detailed understanding of how the radiation escapes.

Two other nearby galaxies are suspected to be leaking radiation, but each has only a tenth as much radiation as J0921. Although starburst galaxies are not generally thought to be leaking radiation, Borthakur said that holes in other compact starburst galaxiesshould be common.

"This is the direct evidence of how the galactic feedback via winds can lead to conditions that allow Lyman continuum to escape," Borthakur said. "This tells us about the physics of star formation and its feedback in the epoch of reionization, and solves the decades-old mystery of how Lyman continuum photons can escape through the cold cloud cocoon enveloping star-forming regions."

The new research is published this week in the journal Science.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd